Last year I wrote a column about a landmark in the place I used to live – the Big Oak Tree outside of Columbia, Missouri, a champion bur oak that is the largest in the state and tied for another in Kentucky for largest in the United States. I wrote that column because, at the time, the Missouri River and its tributaries had flooded, and the Big Oak Tree’s roots were inundated with several feet of water, which I worried would harm the tree. (It turns out that the tree had survived even greater floods than that before – during the flood of ‘93, apparently the water rose to nine feet on the oak’s trunk.)

The Big Oak Tree, submerged, on June 8 2019 [E. Scott]

On Friday, lightning struck the Big Oak Tree. According to one account, the strike was like a detonation: “You could see flames coming out of the tree where a tree limb had been blown off,” one witness claimed. “Some of the limbs were blown 50 yards away. It was like an explosion.” The tree and its fate were the only things my friends in Columbia could talk about that day. We all watched the videos of firefighters boring holes into the side of the tree so they could smother the fires in the tree’s core with foam. (“If the fire doesn’t kill it that chemical foam s— will,” said one acquaintance. “What’s wrong with water?”)

The Big Oak Tree is, by the National Park Service’s estimate, somewhere around 400 years old – nearly as old as the Roanoke Colony, and certainly older than the colonization of the Midwest by Europeans. As many of the officials on the scene noted, it has been struck by lightning before and survived all manner of other calamities in the course of its life. Still, I find myself unnerved by the thought of such an ancient being undone in an instant, however long it might take for the smoldering fires within to finish the task of hollowing it out.

The property owner, John Sam Williamson, said he was hopeful that the tree would make it. “Well, this is an act of God, you can’t really do anything about it,” he said. “It’s Mother Nature, but you know it’s survived things like this before and I think this will probably survive this too.”

An act of the gods, the whim of Mother Nature, yes, all that is true. Still, when something lives for a few centuries, one expects it will keep on living forever. That’s never been true, not once in the history of the Earth, but one can’t help but believe it, regardless.

Bird on a wire [E. Scott]

For a few months now I have been puzzling over an arrangement of the old Scots ballad, “The Twa Corbies.” The ballad is a dark answer to another ballad, “The Three Ravens,” a sad old thing that describes the three birds discussing the death of a knight. The knight is mourned by his hounds — “they lie downe at his feete / so well they can their master keepe” — and his hawk, and most of all by his lover, who carries his body to the shore of a lake and buries it there. “She was dead her self ere euen-song time,” goes the ballad, and concludes on the sentimental note that the Christian god should send everyone such devoted companions and lovers.

“Twa Corbies” takes the plot in a sardonic direction. The two ravens are still talking about a dead knight, but this time his companions are not nearly so attached. His hound and his hawk and his lady all know he is dead, for certain – perhaps they are even complicit. The pivotal verse goes like this:

“His hound is to the hunting gane,

His hawk to fetch the wildfowl hame,

His lady’s ta’en another mate, oh,

So we may mak our dinner sweet, oh,

So we may mak our dinner sweet.”

The humor of the ballad comes in our knowing recognition of such behavior, that when we are at our lowest points at least some of the people we thought loyal to us will suddenly have other places to be. It’s an altogether more cynical view of our relationships with others than “The Three Ravens,” and, as with most cynical perspectives, takes its pessimism as a sign of greater realism. (That the ballad ends with the ravens gleefully describing how they’ll pluck out the fallen man’s eyes and thatch their nests with his golden hair adds to this idea of realism; it does seem altogether more likely than a pregnant woman dragging a dead man across a field to the nearest lake, as happens in the original song.)

That’s just how it reads at first, though. The truth of the ballad, and why I think I like it so much, is that beneath its curmudgeonly presentation, “Twa Corbies” presents a deeper truth: that no matter what calamity occurs, life goes on, in some way or another. “The Three Ravens” has it so that the fallen knight takes his dogs and his lover with him, as though their usefulness to the world ended with him. “Twa Corbies” acknowledges that the hound and hawk will hunt again, and his lady will find company with another lover. Perhaps they could wait a little longer to do these things, and give the knight a proper burial – but still, can we begrudge them moving on with their lives?

Their knight is dead, but they are alive. It is better for the lady to be alive with another than dead with him. Life goes on. That is the lesson.

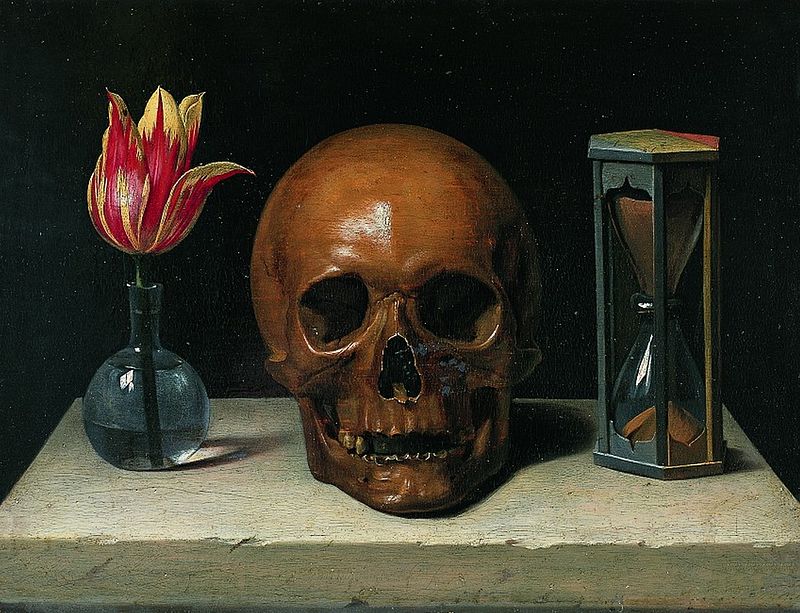

Vanitas, by Phillippe de Champaigne, c. 1671 [Wikimedia Commons]

We are nine days out from the United States presidential election, and at once it seems that there is nothing else to talk about and there could be no other words to say that haven’t already been said ad nauseum. If there is a story worth telling, it is probably that a campaign season with such consistent underlying statistics – Joe Biden has led Donald Trump by about seven points nationally since at least June, with consistent leads in the battleground states as well – still feels so uncertain.

I suspect that – probably – Biden wins, after a few days of hand-wringing as the mail-in ballots are counted. But there are other possibilities, much more anxious ones, that really could happen, up to and including mass political violence. I don’t think it will come to that, but it might. I have never been much of an oracle, and I make no claims to accurate predictions now.

What I do know is that whatever challenges exist on November 2nd will still be there on November 4th, no matter what the outcome is. The terrain of that struggle will change, but the struggle itself will not. There is a temptation, inculcated in us by the nature of American election coverage, to think of every presidential election as a flashpoint beyond which there is no way to anticipate, and that is wrong. Even in the most horrifying futures, life will go on – and we will have to be prepared to live through it.

In all of this, I do not mean, at all, to present the message that it doesn’t matter what happens, that life goes on regardless and there’s no point in worrying – that’s really the opposite of my intention. What I mean is that we should be prepared to continue living, and struggling, no matter what the outcome is.

The COVID-19 pandemic will still be with us; so will police violence against people of color; so will the precarious state of rights for women and queer Americans; so will climate change; so will the possibility of ever-more draconian intrusions of Dominionist Christianity into the lives of Pagans and other minority religions. I suspect many of these things will be more readily dealt with under one presidential candidate than the other, but all of these fights save the pandemic existed before and they will persist in the future no matter who is president in January.

Life will continue; we must be ready for that. Nobody could have predicted lightning would strike the Big Oak Tree last Friday. The fire department still had the chemical foam on hand; they knew that, eventually, they might need to use it.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.