Western constructions of reality are so strong that they often overwrite our understanding of important, seemingly independent celestial events. The solstice is no different. In one sense, it is an astronomical occurrence, leading us to believe it is independent of cultural intrusion, much like how we might like to think mathematics or physics exist – that is, that they are the same no matter who is observing them. But culture has always intruded into our understanding of the world, and, because western culture is so overwhelmingly dominant, we must take extra care to see how different cultures reflect on events that we might think are independent of human interference.

A few weeks ago, the northern and southern hemispheres celebrated the solstice, a celestial event whose date of occurrence might seem fixed and uncontroversial. Still, there are different ways to mark the event. The solstice is perhaps better understood as an event of the northern and southern mid-latitudes and beyond; in the tropics, the “solstice”, per se, is thought of differently.From the “little latitudes,” the progression of the sun still occurs, of course. But as the ancients observed, the amount of daylight in the tropics varies little by season.

Now recall that the zodiac is the apparent elliptical path of the sun across the celestial sphere and marked by constellations. On the northern edge of the Tropic of Cancer, cities like Havana see variations of about three hours between the longest day and the shortest day of the year, both corresponding to the solstices. But along the equator, the difference between shortest and longest days of the year is about 10 minutes, and every day is about 12 hours in length. The analemma, the sun’s bow-shaped path in the sky, reminiscent of an infinity symbol, is fully observed overhead from the equator. Both highlight how differently the path of the sun impacts the various cycles of human life from the agricultural to the spiritual.

The sun’s analemma observed from Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, NJ [Wikimedia Commons].

The Hindu zodiac sidereal system does not shift. It marks the vernal equinox sun’s position on the equator as the origin of latitude, and thus the prime meridian. It marks the seasons not by the position of the sun itself, but rather by the stars behind the sun. It partitions the elliptical journey of the sun using constellations. In a sense, the difference between the western and sidereal zodiacs boils down to frame of reference: the Earth relative to the sky with the sun passing through it, or the Earth relative to the sun with the skies rotating around it.

On January 13, from a western viewpoint, the sun is 23 degrees into Capricorn. In the Hindu sidereal zodiac, on January 14, we subtract 23 degrees (the precessional difference) and the sun enters Capricorn. Happy Solstice!

Well, maybe not quite, but today heralds the entry of the sun into the zodiac sign that underscores the change of season. January 13, in southern Asian cultures, is the last day of Dakshinayana. With its end, the gods awaken from their celestial slumber and we enter a time to realize potential and focus on growing positivity.

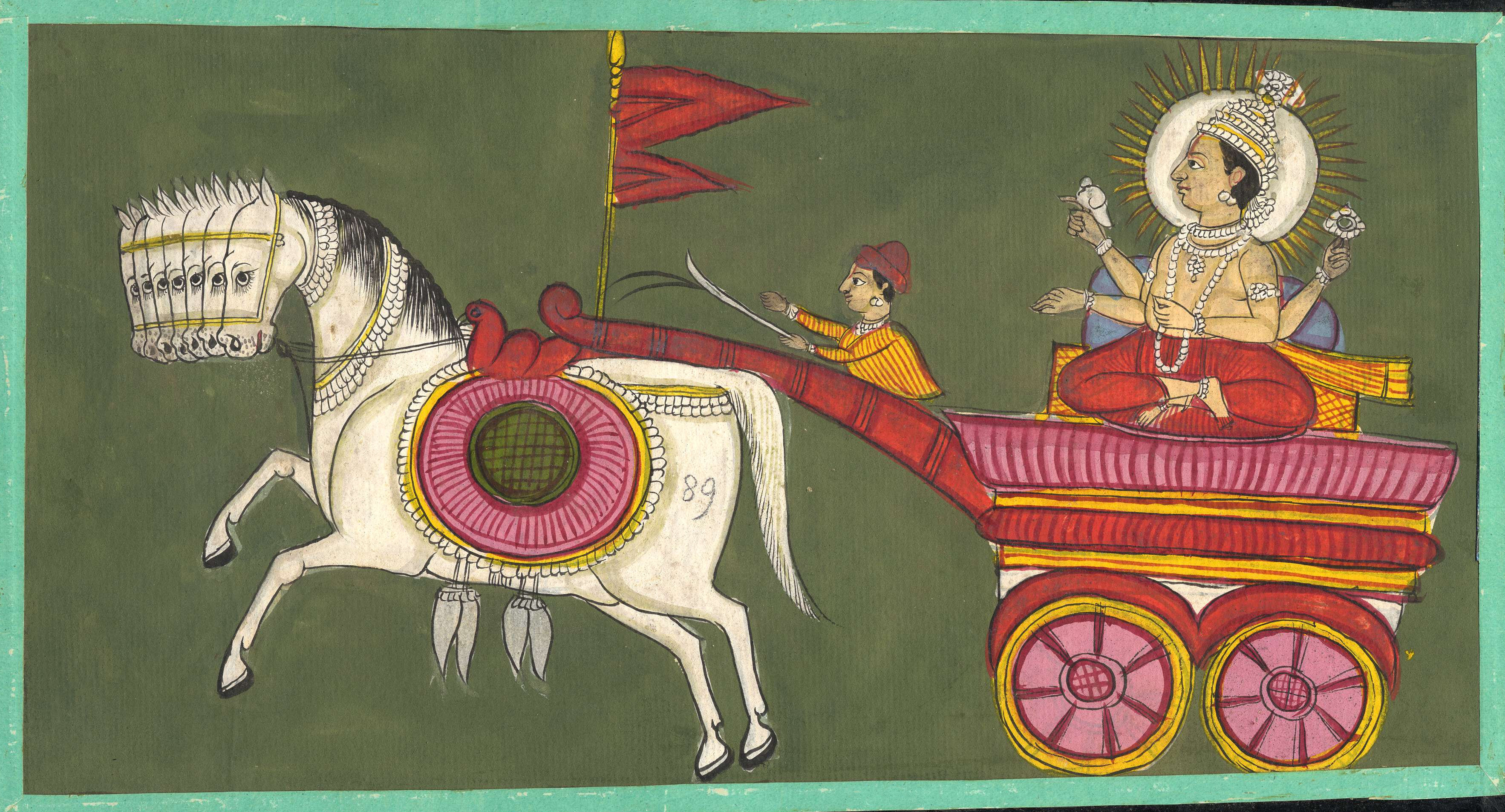

Surya, the sun-god, seated on his chariot led by a horse with seven heads [public domain]

Bhogi is the first day of the festival, when practitioners burn anything that is no longer useful, including furniture. Old and unused items are discarded so the focus can remain on the future. The destruction of old items is also seen as the elimination of bad habits and attachment to material things. The destruction of these items helps us recognize the importance of transformation, purification, and connectedness. The second day, meanwhile, is the main festival day.

On the third day of Makara Sankranti, families remember their ancestors and make offerings to them. Animals are fed and honored, and prayers are offered to various divinities for the coming harvest. Finally, on the fourth day, the elements and, for lack of a better Western term, genius loci are propitiated. In some regions adherents refrain from eating animal products. The day’s celebrations also involve flying colorful kites, symbolizing renewed health and the removal of illness and infection.

In some regional variations, Lohri, as it is celebrated by Sikhs and some denominations of Hindus, is the day before Makara Sankranti and focuses on gratitude to the sun god for the return of light. It marks the beginning of the financial year and also harkens the tale of Dulla Bhatti, a Robin Hood-figure in the Punjab region who freed girls from enslavement. Children also travel neighborhoods singing and requesting treats.

Most importantly, Makara Sankranti is a time to look for opportunities that promote peace. Communities encourage their members to make peace by focusing on prosperity, dialogue and forgiveness.

Thus we see that the spiritual meaning of the solstice echoes, or even harmonizes, across the cultural landscape, even if the same astronomical event is recorded differently.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.