WALES – After a summer in which the drought brought to light a number of interesting archaeological finds in the UK and Ireland, the rest of 2018 has proved almost equally fruitful, with two major discoveries shedding light on our Celtic ancestors and their way of life.

One of these finds is large, the other tiny, but both are the first of their kind: they are a buried Celtic chariot unearthed by a treasure hunter in the Welsh county of Pembrokeshire, and a small metal figure, possibly devotional, found in Cambridgeshire.

The National Museum of Wales has described the chariot burial as ‘significant and exciting’: it is the first such burial unearthed in Wales. Mike Smith, an experienced metal detectorist and a member of Pembrokeshire Prospectors, came across the site (which is being kept secret for the time being) as his usual hunting ground was water-logged. His explorations revealed what he initially believed to be a Medieval brooch, until a contact identified it as part of a horse harness. When Smith returned, he unearthed more pieces, including bridle fittings, tools, and a brooch, with their red enameling still bright, although the bronze itself had become green from corrosion. Smith says

“I knew the importance of them straight away. It was just instinct. I’d read all about chariot burials and just wished it could have been me, so finding this has been a privilege.”

Iron Age Hill Fort Gaer Fawr [Jasperfforde]

It’s probable that ploughing has brought the site closer to the surface. The site is now under legal protection and a fuller excavation is planned when the earth is less compacted, but it is known that there is a significant amount of metal underneath the chariot itself: whether weaponry or treasure remains to be seen.

Authorities say that”National Museum Wales is working with its partners on this continuing treasure case and in developing a detailed and fully funded proposal for further investigation. It is intended that a wider museum project will be developed, to offer opportunities for local communities near the find-spot to engage with this discovery and to become involved in revealing new stories about their prehistoric past.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the UK in Cambridgeshire, a smaller, but equally interesting, find has been made: a two inch metal figurine that is currently being described as ‘a fertility god.’ The figure has no face, but archaeologists are identifying it as the Celtic deity Cernunnos: the most famous representation of this being on the Gundestrup cauldron (we ought to note that identification of this deity is not uncontentious: the name ‘Cernunnos’ is itself used only once, on the 1st C monument known as the “Pillar of the Boatmen”, but it has become attached to representations of antlered male forms found throughout Europe).

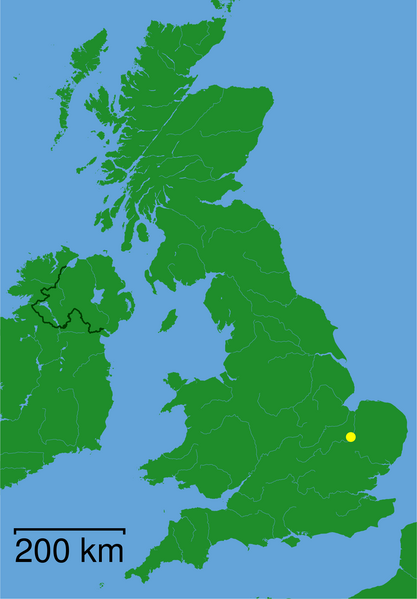

[Cambridgeshire, marked in yellow – Courtesy Wiki-Commons]

Stephen Macaulay, the Deputy Regional Manager at Oxford Archaeology East, says: ‘The face of the figurine has been rubbed away, but we see similar figures of Cernunnos, so it’s like finding a worn version of Jesus on a crucifix, it’s the shape you expect to see. He was an important God to the Celts, but this shows how accepting the Romans were of other religions, they often just merged the Gods with their own. The Romans really ran their empire like the British did, they would conquer and then reinstate the people who had already been in charge. The Wimpole story is interesting as it gives us a snapshot of local people living alongside the legionnaires as they travelled up and down the country along Ermine Street.’

Shannon Hogan, National Trust Archaeologist for the East of England, adds: ‘This is an incredibly exciting discovery, which to me represents more than just the deity, Cernunnos. It almost seems like the enigmatic ‘face’ of the people living in the landscape some 2,000 years ago. The artefact is Roman in origin but symbolises a Celtic deity and therefore exemplifies the continuation of indigenous religious and cultural symbolism in Romanised societies.’

Cernunnos, a popular deity among modern Pagans, is often described as ‘enigmatic’ and this figure, if it is indeed of the god, continues the mystery, as it’s the first metal representation of the deity. It’s made of copper alloy and holds a torc: other representations are all made of stone. It probably dates from the 2nd C AD.

These are significant and exciting discoveries and it is likely that more of interest will be unearthed from both sites over the course of 2019.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.