TWH – North African sybils, Zen-like art, and pan-cultural perspectives infuse new tarot/oracle decks. Here’s a look:

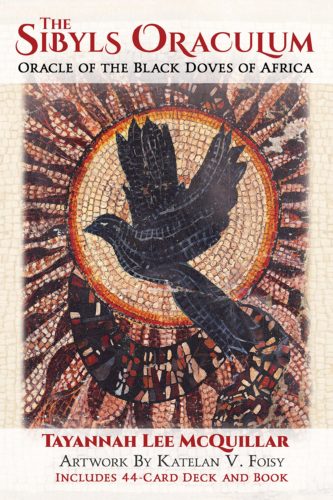

The Sibyls Oraculum: Oracle of the Black Doves of Africa by Tayannah Lee McQuillar, artwork by Katelan V. Foisy, 44-card deck and 148-page guidebook (Destiny Books).

The Sybils, writes Tayannah Lee McQuillar, “were women of the ancient world who were reputed to possess the powers of prophecy or divination . . . . While most people have heard of the oracle of Delphi and are aware of the influence the Nile Valley civilizations had on ancient Greek and Rome, few are aware that the Sibylline tradition began in Africa and that the Greek and Roman cultures were heavily influenced by ancient Libya.”

And this is how McQuillar, whose academic background is in cultural anthropology, sets the stage for this exploration in the chapter “A Brief History of the Sybils” in the guidebook to her rich, multi-layered oracle deck. She quotes the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who said the oracular tradition of Greece originated in Kemet (ancient Egypt) and spread when “two black doves had come flying from Thebes, one to Libya and one to Dodona (in Greece).”

The Sibyls Oraculum: Oracle of the Black Doves of Africa by Tayannah Lee McQuillar, artwork by Katelan V. Foisy

The Sibyls Oraculum: Oracle of the Black Doves of Africa “is not a fortune-telling tool,” says McQuillar, who also is a tarot reader based in New York City. “It is a cartomantic method of divination designed to facilitate self-examination and decision-making to improve the likelihood of success in all undertakings.”

Each of the 44 cards, created by artist Katelan V. Foisy in the style of ancient mosaics, correspond to one or more divinities from the mythologies of ancient Mediterranean cultures, including Libyan, Nubian, Kemetian, Greek, Roman, Phoenician, Canaanite, Etruscan, and others. Such deities include Terminus, the Roman god of boundaries; Nemesis, the goddess of revenge; and Nebt-Het, the “ancient Kemetian goddess of secrets, nighttime, and beer.”

“Myths are real,” McQuillar writes. “They are vehicles of transmission for the teaching of complex concepts and ideas that might otherwise be incomprehensible if explained in more academic or philosophical terms. The divinities represent the fantastic realm of possibilities, positive and negative, within their areas of stewardship while simultaneously personifying the possibilities themselves.”

The 44 cards are divided into four groups: core issue cards, projection cards (described as “the rationalizations or justifications in the querent’s mind”), “cool” action cards (“advice to the querent” concerning his-her “internal state of mind”), and “hot” action cards (“suggested external response to the situation”).

Core issue cards include Mysteria/Mysteries, Numero/Rhythm, Sapientae/Wisdom, Mortem/Death, and others. Projection cards include Furorem/Rage and Libidine/Lust. Cool action cards include Praesidio/Detachment and Cupiditas/Desire. Hot action cards include Castitate/Purity and Ludere/Play.

The guidebook gives a detailed explanation of reading techniques, of course, and descriptions, key symbols, religio-mythological associations, and divinatory meanings for each card.

But the book also moves beyond mythology and into direct self-analysis and Jungian psychology with a list of probing, simple (or perhaps not so simple) questions for each core issue card: “Is there a part of you that feels comfortable being the victim or at least being perceived as such by others?”

“Are you focused on how much more you could have received instead of how much you’ve already received?”

“If something went wrong, did you really not know or see it coming? Or did you willingly let someone/something slide because it was comfortable for you to do so at the time?”

McQuillar also wrote thought-spurring epigrams in the guidebook for each card. For the Adversus/Opposition card, it’s “Adversity is desire’s unwanted child.” For Mortem/Death: “Only distance is death.” For Habitum/Disguise: “Deception feeds and protects all life.”

Surprisingly, McQuillar even states it is OK for deck readers to gloss over or disregard the deity associations of each card, noting they are “not necessary for the oracle to work.” She also suggests readers “further investigate the esoteric significance of each deity as designations such as ‘Crocodile God’ are overly simplistic and at times merely condescending colonial attitudes toward non-Abrahamic belief systems . . . .”

Whatever divinatory power the Sibyls Oraculum may unleash, and however successful McQuillar may be in revitalizing the traditions, myths and weltanschauung of ancient, indigenous North African peoples, her deck and book undoubtedly will open doors to inner explorations.

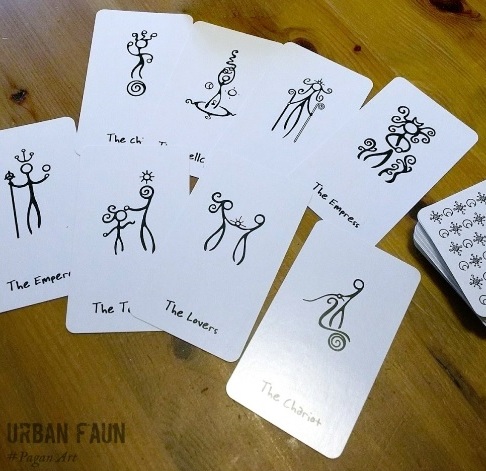

The Child Tarot by Joanne Dunster [Photo from urbanfaun.com]

How many of the ever-proliferating decks in the world of tarot are “based on the Rider Waite”? The Child Tarot is not one of them.

At first glance, The Child Tarot is, well, child-like. In the companion booklet (available only as an online, printable download), creator Joanne Dunster even confesses that her artwork “is rather sparse.”

She was inspired to create The Child Tarot after she had “bought a cheap and quite terrible deck and was musing on its imagery and meaning, and I just started drawing like mad,” she writes.

“I was expressing both my frustrations with the horrid deck I had purchased and exploring my emerging understandings of the cards mixed with other imagery and names that have strong meaning to me. In essence The Child Tarot was an exercise in teaching myself the tarot.”

But Dunster’s minimalism is deceptive. Her stark images resonate in much the same way as do Egyptian hieroglyphics, Zen art, the Neolithic swirls and triskelions of Newgrange in Ireland, and the petroglyphs of the ancient Anasazi.

Her stick figures, so to speak, are composed of graceful swirls, circles and squiggles that exude energy and motion, in order that the Spellcaster – her card for the Magician- vibrates with primal, kinetic alchemy. The falling figures of the lightning-struck Tower are indeed disturbing and tragic.

The minor arcana is even more basic, consisting of Dunster’s icons for cups, swords, wands, and discs arranged in various patterns (except for the court cards). But even those arranged icons convey the mystery and vigor of sacred geometry.

Tarot readers may be surprised (but shouldn’t be) by the radically different energy that emanates from, say, the swirling, Newgrange-like designs of the Two of Discs compared to the same swirls in the Three of Discs.

The deck’s booklet includes discussions of each of the major arcana, but virtually no insights on the minor arcana and only a cursory discussion of a basic three-card reading technique.

The temptation is to say that readers of The Child Tarot deck should familiarize themselves with the minor arcana meanings of the Rider-Waite or other more traditional decks. But the perhaps better advice is that The Child Tarot, given its Rorschach nature, is far more engaging if it is not someone’s introduction to the world of tarot. That said, the deck — especially its major arcana — can communicate and connect to someone without any familiarity with the Rider-Waite tradition.

Dunster, who notes she is Wiccan, says she has discovered her deck “to be not always a very subtle deck and sometimes quite blunt in its advice.”

She adds that she is “constantly surprised to find more symbolism” in her deck upon repeated uses – “things I didn’t even know I put there! It is strange how much a few squiggly lines can portray. I think that this is the enduring nature of the symbolism of the tarot. It seems to bubble its way to the surface in the human mind given even the slightest chance.”

The High Priestess card from the New Era Elements Tarot by Eleonore Pieper. [Photo from deviantart.com]

The Dalai Lama is the Hierophant in Eleonore Pieper’s New Era Elements Tarot. The Three of Fire card, Exploration, is the space shuttle. The Devil card portrays children who died during the civil war in Rwanda lying beneath a Nazi swastika, the Russian communist hammer and sickle, and a dollar sign.

“Similar in look and feel to my Harry Potter Tarot, this one is not a fandom tarot, but a personal interpretation of the iconography of traditional decks such as the Rider-Waite and the Thoth,” Pieper writes on the website deviantart.com.

“The deck is based on a strong concept of the four elements. Its themes, while reflecting the archetypes associated with each card, is based on contemporary subject matter.”

The exquisitely detailed, black-pencil illustrations on Pieper’s cards draw from such peoples and cultures as the Himba of Namibia, the Goans of India, the Masai, the Maori of New Zealand, and many more.

As for the couple on the Lovers? They are Pieper’s parents, she says.

Animal imagery abounds, too. The Five of Air card, Defeat, depicts a spider encasing a locust trapped in its web. Hawks, dolphins, crows, lions, leopards, and other creatures are at the heart of other cards.

The minor arcana suits are fire, water, air and earth.

The card explications on the website are insightful and detailed, sometimes personal yet often filled with a pan-cultural awareness, while Pieper frequently draws comparisons to Aleister Crowley’s Thoth deck.

“My parents weren’t soulmates, they were flawed and amazing human beings who worked every day to fit themselves around each other and around their family,” Pieper writes about the Lovers card.

“To me they embody the complex meaning of the card — something new created from love, and love not the happily ever after of fairy tales but a daily choice to support one another, to overcome personal egotism to be there for someone.”

Pieper writes that Crowley “associated the High Priestess with the Egyptian goddesses Isis and Neith and the Greek Artemis. In his Thoth deck he gives her a bow instead of a book and she herself holds and lifts the veil that covers her.

“There is a lot of hinting at the eternal feminine mystery and veils/hymens, to the point that for a female reader the whole working with this card can become somewhat tedious. In my design I got rid of some of the traditional iconography that makes the High Priestess look somewhat of an avatar of the Virgin Mary as well as Crowley’s chauvinistic projections.”

Pieper goes on to confess that “the artist is the High Priestess.” Yes, it’s a self-portrait.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.