[Columns are a regular weekend feature at The Wild Hunt. Each Friday and Saturday columnists from various backgrounds and traditions share their perspectives and add their insights to the larger conversation in the community. If you like this feature, consider making a small monthly donation or make a one-time donation toward this vital global community venture. Either way, it is your help and your support that keeps daily and dependable news coming to your doorstep each day from wherever its origin.]

I went to Tampa for a conference last month. This had the pleasant side effect of putting me within driving distance of my best friend, who moved to Florida for a job not long ago. I skipped most of the Saturday events to see him. We spent most of the day at the Florida Aquarium – an institution which mysteriously houses a set of lemurs as its most publicized exhibit – but as the evening wore down, we retired to my hotel room and he asked the question that has been the refrain of our friendship since we were teenagers: “So, do you want to play a game?”

My friend loves board games. He is one of those people who collects board games the way other people collect DVDs or commemorative plates; his home has a shelf full of boxes containing boards and pawns and cards. Board games have never been my favorite nerdy vice, but I play them because he likes to play them. And seeing as he has driven three hours to see me, I figure I at least owe him a game.

The box-art to Spirit Island. [Greater Than Games]

I won’t go through all of the rules here – for that I refer you to an excellent piece on Ars Technica by Aaron Zimmerman – but in short, in Spirit Island the players portray the elemental spirits of an island being discovered, invaded, and colonized by European settlers. Left to their own devices, the Europeans will inevitably despoil the land as they ravage its natural resources; they will also come into conflict with, and eventually wipe out, the indigenous people of the island. The players must work together to oppose the colonizers, either by violently destroying their settlements and their exploring parties or by terrorizing them into fleeing the island.

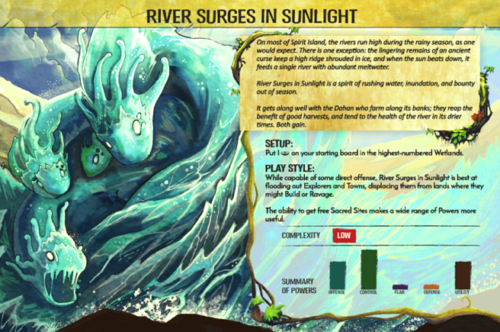

The different spirits, naturally, take different approaches to this task. The storm spirit, named Lightning’s Swift Strike, attempts to build up its resources so that it can unleash one massive turn of attacks, for instance, while the water spirit, River Surges in Sunlight, is adept at moving elements around the board, pushing the invaders to where they will do the least damage. The stone spirit, Vital Strength of the Earth, is tough but slow; the spirit of darkness, Shadows Flicker like Flame, excels in terrifying the colonizers and building up their fear of the island to the point that they abandon their colonies and return to their ships. Each spirit plays quite differently, and the close match between the game mechanics and the personality of the spirit is one of Spirit Island’s most distinctive features.

The human characters, in my experience, are more of a mixed bag. Like the spirits, the invaders are customized from game to game; their mechanics are determined by their nationality, so that if the island is being colonized by the English, indentured servants will spread to take more land, while if the invaders are Swedish, they will more heavily mine the island’s natural resources and cause more damage to the landscape.

While the colonizers are individuated, the indigenous humans are a fictional group called the Dahan. In the game’s rulebook, R. Eric Reuss, the designer, noted that he might have gone a different direction with the theme: “In retrospect,” he writes, “I could have gone an entirely different route: find a specific colonial-vs-anticolonial struggle to try and model… Instead, my brain imagined a conflict that never was, but which could serve as a stand-in for struggles against different imperial powers throughout history.”

Despite Reuss’s explanation, I find myself uneasy at the way the game gives historical specificity to the European colonizers, but we get no similar specificity to the colonized; it seems to reinforce a narrative that indigenous people are essentially the same everywhere. It’s more sympathetic than simply labeling all indigenous peoples as “savages,” but I would have preferred the game either using an entirely fictionalized conflict or an entirely historical one, as opposed to its current half-and-half approach.

River Surges in Sunlight, one of the spirit characters in Spirit Island. [Greater Than Games]

The worst I can say about the metaphor of Spirit Island is that it begins too early. Like Catan before it, Spirit Island begins its story with the “discovery” of an island by the colonizers; it’s from that point of discovery that the pattern of conquest and ravaging starts. While it is useful for us all to know and understand that history, we are ourselves not in that moment. We are now living in the aftermath of a game that began centuries ago, in which the colonizing forces have been steadily expanding and ravaging for too many turns to count – and in which we all continue to be complicit, whether we wish to be or not.

The land spirits of our time are enacting their own campaign of resistance and destruction to try to quell our attacks on the earth (we call these actions “climate change”). In Spirit Island, the actions of the invaders are automated; they have no choice but to continue their campaign of expansion and destruction. We, perhaps, have more agency than that, and can choose to act otherwise. But the time we have left to exercise that agency is limited, if we still have it at all – we’re either going to find a way to make peace with the land spirits, or it’s going to game over for all of us.

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

Save Pagan journalism

Donate today

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.