The Ásatrú religion can offer new perspectives on climate change ethics via examination of the modern practice of historically grounded ritual known as blót – a rite that foregrounds reciprocity with the earth, inherent value in the natural world, transtemporal human relationships, global connectedness, and the consequences of human action. In addition to discussing Ásatrú textual sources and examples of ritual, this column offers a new ethical model for responding to issues of climate change.

Ásatrú is a religion with a life that already relates to reality in a way that addresses major issues raised by climate change ethicists. Practitioners are both certain and competent in a life-practice that directly engages relationships within the transtemporal human community and with the wider world.

Through study of lore and celebration of ritual, the practice of Ásatrú reinforces understanding of reciprocal relationships with the natural world, inherent value of living things, connections to past and future peoples, interrelatedness of all human actors, and consequences of human actions. Specifically, the ritual of blót serves as a model for addressing multiple problems of climate change ethics.

The Ritual of Blót

In the mythical poetry written down in thirteenth-century Iceland, the deities themselves hold blót, sometimes to each other. The goddess Freyja sacrifices to Thor so that he will grant her request to be friendly to a certain giantess, despite his sworn enmity to the giants. Emphasizing an ethic of hóf (“moderation”) and reciprocity, the god Odin warns his followers that it is “[b]etter not to pray than to sacrifice too much: one gift always calls for another.”

The root of the ritual is a reifying of reciprocal relationships between the performer(s) of the ritual and the receiver(s); a gifting cycle is established and maintained in which, according to Odin, “mutual givers and receivers are friends for longest, if the friendship keeps going well.”

The word blót (“sacrificial worship”) and the paired verb blóta (“to sacrifice”) likely have an original meaning of “to strengthen (the god).” By making an offering to strengthen the deity, the follower hopes to receive a favor (general or particular) in return.

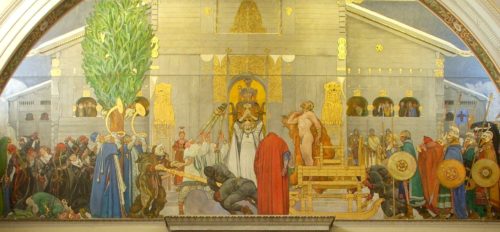

Midwinter Blót by Carl Larsson (1915) [public domain].

Today, the great violence of the Uppsala rite is a distant relic of history, and modern blóts tend toward the second example. The most common offerings are of alcoholic beverages – usually beer or mead, often home brewed. Throughout the year, blóts are held as part of a cycle of annual rituals, to celebrate life events, and at a community’s need.

Earth Goddess and Land Spirits

Even when the ritual is focused on a particular deity or celebratory occasion, the performative act of modern blót centers on an understanding of human life as directly engaged with the earth and environment. Although there is a great variety of ritual praxis throughout the Heathen world, it is common to open blóts with the Valkyrie’s prayer from the Old Icelandic poem Sigrdrífumál (“Sayings of the Victory-Inciter”).

The Icelandic Ásatrúarfélagið uses the two verses as a standard ritual element, and the U.S.-based international Heathen organization known as the Troth includes them as part of its wedding ceremonies. In the United States, the 1923 translation by Henry Adams Bellows remains popular:

Hail, day! Hail, sons of day!

And night and her daughter now!

Look on us here with loving eyes,

That waiting we victory win.Hail to the gods! Ye goddesses, hail,

And all the generous earth!

Give to us wisdom and goodly speech,

And healing hands, life-long.

The earth appears twice in the poem, once in each verse. The second line of the first verse is usually read in light of Snorri Sturluson’s Edda of c. 1220, in which the Icelander states that the earth goddess Jörð (“Earth”) is the daughter of Nótt (“Night”). Although Bellows translates in fjölnýta fold as “the generous earth,” the word fold (cognate with English “field”) refers to earth as soil and ground rather than as concrete deity.

So, whatever the specific occasional context, recitation of the Valkyrie’s prayer focuses the attention of the ritual participants on the earth both as anthropomorphic goddess and as physical provider of sustenance.

Arthur Rackham’s illustration of the praying Valkyrie (1915) [Public Domain]

The Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniæ, an ordinance issued by the Christian Charlemagne for governance of the pagan Saxons in c. 785, levies monetary fines for making “a vow at springs or trees or groves” or “partak[ing] of a repast in honor of the demons.” Reading through the condemnatory language, this seems to refer to Saxon analogues of the pre-conversion Icelandic veneration of land wights and human consumption of the meat offered in blót after the conclusion of the ritual.

Written sources of medieval Iceland portray land wights as living in trees and boulders, as anthropomorphic “rock-dwellers” who “bring fruitfulness to their friends [and] also give wise rede.” A strong sense of reciprocal relationship with the land wights continues in Iceland today, where the concept of the landvættir sometimes overlaps with that of the álfar (“elves”), an originally distinct type of beings who may have once represented the spirits of departed ancestors. Government road construction projects are still rerouted around boulders believed to be elf homes.

In 2012, a member of parliament personally paid to move an enormous stone from the mainland to his residence in the Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands) after – according to elf specialist Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir – the elf family that inhabited it saved his life during his car accident in its vicinity. Underlying the various conceptions is the idea of independent life in the natural world, of conscious creatures that embody or inhabit both animate and inanimate things.

Offering and Inherent Value

Lafayllve suggests a variety of items that modern Heathens can offer to land wights in their local vicinity, including milk, butter, beer, mead, cider, honey, oats, barley, fruits, herbs, and vegetables – “particularly during their respective harvesting seasons.” The offerings are either natural objects or traditional products made directly from them.

Kirk S. Thomas, former Archdruid of Ár nDraíocht Féin: A Druid Fellowship but a pagan theologian much respected by American Heathens, emphasizes in Sacred Gifts: Reciprocity and the Gods that offerings to nature deities should not be plucked from natural settings, but “must be something that the giver has a right to give.”

Lafayllve’s list of offerings underscores this idea; the optimal gift is something that the giver spent time cultivating or crafting from natural ingredients. A secondary option is to purchase these items using one’s own earned income. In either case, the nature of the object offered foregrounds a reciprocal relationship with the natural world that acknowledges the cycle of cultivation, craft, consumption, and gratitude.

An Ásatrú worldview – as reflected in the ritual of blót – sees the earth, elements of the environment, and “non-human species” as entities with individual agency. There is no sense of ex nihilo creation in Heathen lore; the material universe predates the birth of the gods, who themselves are craftsmen and organizers – demiurges, in the original sense – rather than all-powerful creators. Instead, the earth and elements of the natural world are addressed as enchanted and active anthropomorphic beings who have value in and of themselves and with whom we must build relationships of reciprocity.

Rather than relating to the natural world as a vessel for the transmission of a creator god’s divinity, the practice of blót reinforces a sense that the earth is an active agent with value intrinsic to its own distinct being. The land wights, while lesser Powers than the earth goddess, are also given veneration in a way that focuses the community’s attention on its multiple levels of relationship with the environment. The anthropomorphic conceptualization of trees, rivers, and other aspects of the environment necessarily fosters a sense of relationship with active partners that deserve respect.

Detail of Religion by Charles Sprague Pearce (1897) [public domain].

One in a string of these addresses is performed like this by the group as it stands around the oak tree dedicated to the god Thor:

Goði: Jörð, earth goddess, giver of plenty, we thank you for the gifts of sustenance you give us, despite our mistreatment of you. We ask that you continue to share your bounty with us as we work to protect you from our own misdeeds. Hail Jörð!

Kindred members: Hail!

Goði drinks from the horn, then pours a draft for Jörð into the soil at the base of the tree.

A standard Thor’s Oak Kindred blót includes such individual addresses to the divine trio Odin, Thor, and Freyja; to the cosmic trio Jörð, Sól (“Sun”), and Máni (“Moon”); and to the land wights. Given the fact that the Valkyrie’s prayer is recited to begin the blót, the earth is specifically addressed three times – two times more than any other Power.

The land wights of the areas inhabited and traveled through by the kindred are also honored at blót. In this ritual performance, the community reminds itself of its relationship to the earth and the environment through engagement with the anthropomorphic Jörð and landvættir.

Well over two centuries ago, Immanuel Kant wrote that the repeated ritual act of communion

contains within itself something great, expanding the narrow, selfish, and unsociable cast of mind among men, especially in matters of religion, toward the idea of a cosmopolitan moral community; and it is a good means of enlivening a community to the moral disposition of brotherly love which it represents.

By regularly standing together at blót and reaffirming commitment to a reciprocal relationship with Jörð and landvættir, Heathens move beyond solo rituals of devotion – which can tend towards a focus on the desires of the individual – and engage in a group rite promoting the growth of a Kantian moral community that engages with the planet and non-human species in a deeply emotional way. The act of participating in blót promotes a mindset of mindfulness specifically oriented towards respect for the environment.

In Iceland, the Ásatrúarfélagið’s annual calendar of five major blóts includes Landvættablót, a ritual specifically dedicated to the land wights. Goði Haukur Bragason states that the ceremony functions “to keep the land strong and remind the people that we are guests here.” Staðgengill Allsherjargoða (“Deputy High Priestess”) Jóhanna G. Harðardóttir underscores the reciprocity of the relationship celebrated at Landvættablót:

We made a contract when the settlers came to Iceland; they [the landvættir] would let us pass and live here, and we would take care of the land and treat it well. The story is told in Landnámabók [“Book of Settlement,” literally “land-taking”]. The landvættir have kept their part of the bargain. It’s a question if we are doing the same. This blót is for them, remembering our deal, thanking them. The blót is for reminding us to do our best, too.

Jóhanna’s statement reflects the dual function of blót discussed above: recognition of a reciprocal relationship with the land and a Kantian direction of community attention to moral issues of engagement with the environment.

The Troth has an annual ritual calendar that includes several rites based on the traditional agrarian year of northern Europe, including Charming of the Plow (“ploughing of the first furrows”), Loaf-Feast (“start of the grain harvest”), and Winternights (“end of the harvest”). Few if any members of the organization are full-time farmers, yet the rites are celebrated even by urban practitioners in order to maintain a connection to the earth as a source of sustenance – “the generous earth” of the Valkyrie’s prayer – and to reaffirm respect for those who work with the earth to provide for the needs of others.

The Troth’s massive compendium of lore, theology, ritual, and practical advice called Our Troth suggests that “Heathens today might want to find out when the fields of the major crops in their areas are ploughed and sown, and hold a ‘Charming of the Plough’ observance at that time,” thus ritually endorsing the emphasis on locally sourced food that has been embraced by environmental activists.

The second part of this column will address transtemporal care and the web of wyrd.

Sources for the first part of this column include A Book of Blots (Members of the Troth), Dictionary of Northern Mythology (Rudolf Simek), Edda (Snorri Sturluson, trans. Anthony Faulkes), History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen (Adam of Bremen, trans. Francis J. Tschan), Life of St. Columban (Jonas of Bobbio), Our Troth (ed. Kveldúlf Hagan Gundarsson), The Poetic Edda (trans. Carolyne Larrington), Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone (Immanuel Kant, trans. Theodore M. Greene and Hoyt H. Hudson), and Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History (ed. Dana Carleton Munro)

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.