This is not fake news.

Over the past six months, there have been increasing concerns about the validity of news media content. A report might come out, for example, discrediting a politician or a government program. This article is then followed up by reports discrediting that report, which is then followed by reports discrediting the writers discrediting the original report. Then, a day later, another report comes out discrediting the media outlet that didn’t report on the discredited report, and so on and so forth, until president-elect Donald Trump takes to Twitter and types the words, “Fake News!” as if he were still on The Apprentice firing a hopeful contestant.

![[Pixabay]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/fake-1909821_1280-500x342.jpg)

[Pixabay]

Outside of the framework of current politics and the recent shower of potentially incriminating evidence, that scenario, and others like it, illustrate a very serious cultural issue concerning truth in media. In December, Facebook announced that it would be implementing new systems to ostensibly curb the sharing of so-called fake news on its platform, beginning with what it labeled “the worst of the worst.”

The social media giant has been under scrutiny for its role in the spread of false news stories and, in fact, this has recently gotten the company into legal trouble. According to a Jan. 12 BBC report, Syrian migrant Anas Modamani has filed a lawsuit against Facebook for not removing posts and reports that falsely accuse him of being a terrorist. He told the BBC, “Not all fake news is illegal, but where it amounts to slander, as I believe this does, then it should be taken down.” A court date is set for Feb. 6 in Wurzburg, Germany.

Facebook is not alone in this problem. Twitter, Tumblr, and others have all been implicated as accessories, if you will, to gossip. In fact, Reddit and 4chan have been directly accused in the recent controversy concerning Trump’s doings in Russia. On Friday, BBC director James Harding said that his agency would be stepping up its own “Reality Check” processes to curb the spread of fake news.

But this problem isn’t one that the social media giants can control; nor is it one that journalists and the media industry as a whole can solve alone. In fact, the creation and sharing of fake news or the misinterpretation of media output are not issues even unique to our contemporary digitally-infused world. Such issues have been ongoing, most assuredly, since even before the days of the town crier and the posted community news bulletin.

Regardless the problem is real and quite serious, and now it is exacerbated by digital media’s ease and fluidity of production and distribution. In other words, the internet has taken our traditional news culture, injected it with steroids, and placed it on the front porch to wave at passersby. The intrinsic good and bad in our very basic human communication skills are now supersized and prancing around with wild abandon.

If we look more closely at this fake news issue, it can roughly be broken down into three main areas: Propaganda, Falsehoods, Misreads. Propaganda is generally created and used by a government to manipulate the populace. Falsehoods can be outright lies, sensationalism, or simply errors within news articles. Misreads are just that, misinterpretations by the reader.

“Propaganda (or how we learned to stop worrying and love Stalin)”

Let’s go backward in time to another moment in history during which the U.S. government colluded with Russia in order to manipulate the American populace. I don’t mean the past few days or even years. While recent reports point to Russian influence affecting a presidential election, there was a time when the government created a Russian-based mythology in order to help start a war.

Prior to 1938, the American public was not interested in getting involved in World War II, and it generally held a low and even fearful opinion of the Soviet Union, which was at the time tightly controlled by Joseph Stalin. In Film Propaganda and American Politics, James E. Combs writes that the United States made a “quick and effective mobilization of propaganda […] to shore up morale in the citizen and military populations, to demoralize the enemy”and to gain support for the allies, including the Soviet Union.[i]

One way it accomplished this was through film, a popular art form that was readily recognized for its ability to influence the masses. Stalin himself has been quoted as saying, “Film is the greatest means of mass agitation.”[ii]

Through its Office of War Information (OWI), the U.S. government leaned on Hollywood, as well as other cultural industries, to support and encourage the war effort. When the propaganda campaign began, OWI set up a film bureau, which by 1944 was reportedly reviewing nearly all films being produced. It was a time of extreme censorship for an industry that was already manipulating American culture through its own tight censorship controls. (But that’s another story for another time.)

Through its Office of War Information (OWI), the U.S. government leaned on Hollywood, as well as other cultural industries, to support and encourage the war effort. When the propaganda campaign began, OWI set up a film bureau, which by 1944 was reportedly reviewing nearly all films being produced. It was a time of extreme censorship for an industry that was already manipulating American culture through its own tight censorship controls. (But that’s another story for another time.)

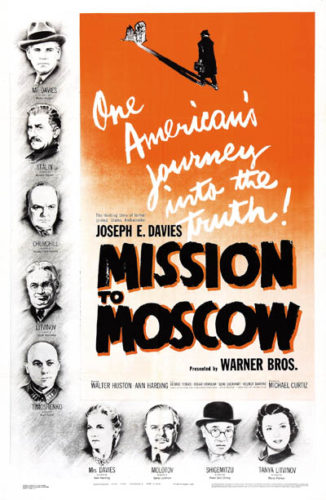

While there were virtually no Soviet-based films made prior to 1939, Hollywood produced a number of pro-Soviet films during the war era. The most notorious of these was called Mission to Moscow (1943), based on a 1937 book of the same name written by the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph Davies. The book and the film justified many of the atrocities known to have been committed by Stalin, and they ignored those that were unable to be spun in a positive way. Soviet officials provided stock footage and applauded the film.

Through Mission to Moscow and similar pro-Soviet films, the OWI falsified a reality in order to create a digestible myth that would allow an American public to accept the Soviet-American alliance during WWII. However, when that war ended and the Cold War set in, the Stalin myth was quickly tossed out, quite literally with regard Mission to Moscow. The film was ordered destroyed.[iii]

“But then again maybe we don’t”

In its place came a new propaganda. As early as 1947 with the birth of the CIA, the wheels turned quickly as U.S. government reportedly began to use art and culture to wage war against its former ally. In a 1995 article for the Independent, journalist and historian Frances Stonor Saunders explains, “Dismayed at the appeal communism still had for many intellectuals and artists in the West, the new agency set up a division, the Propaganda Assets Inventory, which at its peak could influence more than 800 newspapers, magazines and public information organisations.”

The new CIA propaganda agency placed agents in various cultural industries to promote and sponsor American products, from musical performances to the famous Fodor’s travel guides. For example, the CIA reportedly subsidized the animated production of George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1954).[iv]

While this may begin to sound like a conspiracy theory, Saunders reports that former CIA case officer Donald Jameson eventually “broke the silence” and admitted that the agency did, in fact, promote cultural products, specifically abstract expressionist art and the avant-garde movement. Jameson said, “It was recognised that Abstract Expression- ism was the kind of art that made Socialist Realism [popular in the Soviet Union and parts of Europe] look even more stylised and more rigid and confined than it was. And that relationship was exploited in some of the exhibitions.”

Saunders goes on the detail just how the CIA accomplished this propaganda roll-out, soliciting the help of American millionaires and a variety of national leaders. She quotes Jameson, saying:

We wanted to unite all the people who were writers, who were musicians, who were artists, to demonstrate that the West and the United States was devoted to freedom of expression and to intellectual achievement, without any rigid barriers as to what you must write, and what you must say, and what you must do, and what you must paint, which was what was going on in the Soviet Union. I think it was the most important division that the agency had, and I think that it played an enormous role in the Cold War.

These are just two historical accounts of how media and culture were manipulated in order to sway public opinion for the benefit of political movements. While they are not the only instances, together the two provide an interesting example of how the propaganda engine can swing to extremes in only a few short years.

“Remember the Maine!”

Falsified mythologies or exaggerated reports are not always the product of government propaganda. This leads us directly to a discussion on yellow journalism, a term now being used quite liberally to define modern media. Just like propaganda, yellow journalism is a real thing, but it is not a new concept.

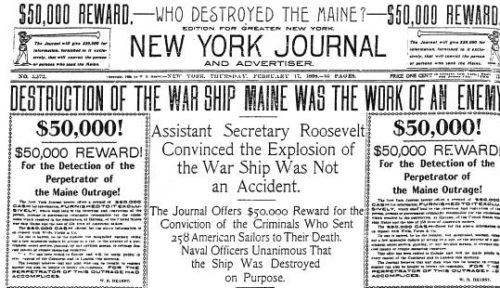

What is it? Yellow journalism is defined by its sensationalist headlines followed up with limited and poorly researched content. It is also categorized by exaggerated and even false reports, all with the aim of emotionally manipulating the reader to increase following. The term, “yellow journalism,” was coined in the late 1800s when two New York newspapers, The New York Journal and The New York World, began sparring. “Yellow” reportedly comes from the name of a character created by the popular cartoonist who sparked the battle.

In an article for The Big Think, writer Paul Ratner details the historic developments that, at that time, were blamed on the proliferation of yellow journalism. Ratner writes, “To draw in more readers, Hearst and Pulitzer resorted to other methods like sensationalist headlines (which today we call “click-bait”), often misreporting or exaggerating the impact of events. The headlines would often try to scare the reader, while the content hit hard on emotion, fake interviews, pseudoscience, often offering some kind of anti-establishment fight, investing the reader with the plight of a supposed underdog.”

Ratner goes on to explain how the newspapers, whose focus was the Cuban political crisis, helped lead the country into the Spanish-American War, which in turn led to a new American colonialism and more war. He writes, “Newspapers pushed the situation onto the American public in such dramatic, often untrue terms, that they were eventually seen as responsible.” However, as Ratner rightly remarks, it is hard to say how much actual influence the two main papers had because they were both part of the New York-based news industry and, unlike today, there was no internet sharing.

While the internet didn’t create this click-bait problem, it has certainly supersized it. The yellow journalism of today manifests in thousands of sensationalized titles leading to little or no depth of text, to reports without corroboration of evidence, and to the erroneous insertions of moral judgments and opinions into what claim to be objective news articles. In fact, BuzzFeed has been criticized for this very thing in its sharing of the Trump dossier.

In an article titled, “BuzzFeed drops a Trump bombshell, irresponsibly,” Poynter‘s Kelly McBride discusses the issue, saying, “The act of publishing the dossier in its entirety isn’t journalism.” She wished that BuzzFeed had offered a more nuanced approach to its presentation and work.[vi] Was it yellow journalism or was it serving the American public? BuzzFeed says it was its responsibility to the public; others disagree.

In her article, McBride discusses the contemporary and legitimate ethical issues facing journalists and editors on a regular basis. Similarly, on Jan. 4 Wall Street Journal article, editor-in-chief Gerard Baker also dives into ethical dilemmas, focusing on the use of the word “lie,” which he notes implies a judgment by the writer on the speaker’s content. As Baker writes, “editors should be careful about making selective moral judgments about false statements.” He advises using the term “falsehood” or “false statements” rather than “lie.”[v]

Ethics and transparency in journalism are crucial, but they are not always easy.

“Chicken Little reports on the falling of the sky. News at 11.”

Finally, there is one more component to the fake news problem, and it lies with the general public: misreads, misinterpretations, and confusion. This is the one of the biggest pitfalls found in our fast-paced social media world. We move too fast. For example, readers don’t stop to observe an article’s date before sharing, or users may even re-post something based only on the headline. Still there are other times when a reader won’t notice that an article is farce, satire, fiction, or opinion.

Over the years, The Wild Hunt has reported on a number of cases in which a story went viral simply through user misinterpretation, including the 2014 Union Witch Trial that actually happened in 2000, or the false assumptions that murder victim Jacob Crockett was an occult practitioner. The former was caused by date issues, and the second was created by false assumptions on the part of a well-meaning Facebook public.

This happens regularly, and is also illustrated by the German lawsuit mentioned earlier. In our social media driven world, these accidents of understanding are hyper-realized, because anyone can manipulate and replicate data. And once something is out, it spreads fast. However, again, this problem is not new to our time.

Before looking at some historic examples, it must be noted that these misinterpretations or misreads can also be, in part, the fault of the producer – accidentally or not.

![Orson Welles explains to reporters that he didn't intend to cause public panic. [Photo Credit: Acme News Photos]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Orson_Welles_War_of_the_Worlds_1938-500x380.jpg)

Orson Welles explains to reporters that he didn’t intend to cause public panic. [Photo Credit: Acme News Photos]

There has been speculation on whether Welles and his collaborators crafted the radio broadcast specifically to trick listeners by removing key parts that would tip them off. However, Welles always denied it, and many people do believe that there were enough markers to indicate the show was fiction. There is also evidence that “the public panic” was not nearly as big or widespread as the contemporary newspapers originally reported. Either way, some listeners did go wild, the FCC and CBS reportedly received complaints, and Welles made history.

Another similar case happened in 1999 when indie filmmakers Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez released The Blair Witch Project and the SyFy Channel mockumentary Curse of the Blair Witch. In this case, the goal was to manipulate the audience, and it worked perfectly. The Blair Witch Project became an instant success, and is still recognized as a brilliant media experiment in public manipulation, demonstrating how easily it can be done.

In the above examples, the cultural products were not well marked, either by accident or on purpose. Hyper critical readers may have noticed that they were fiction, but the vast majority did not, causing confusion, excitement, or frenzy. In both cases, trusted media modalities — radio news broadcast and documentary film styles — were used to convey a feeling of reality to a fictional piece, but both failed to keep enough fictional markers to properly inform their audiences.

If something is not clearly marked as fiction, satire or advertising, which legally has to be done, readers will become confused, leading to the propagation of fake news.

![[Courtesy The Blair Witch Project media material]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/1-The-Blair-Witch-Project-500x273.png)

[From The Blair Witch Project media material]

“Fake news. The biggest fake news.”

In whatever form it takes, fake news is a serious concern, and it is one that all of us must manage; writers, readers, editors, artists, and leaders. That is a tall order, especially in a digital world where emotions drive content and where the immediacy of response, absent all discretionary controls, supersedes reasoned research and composed reaction. The speed of digital sharing, the ease of creation, and the ever presence of digital devices is what has made a very age-old problem a supersized monster.

Fake news is a subjective term on its own perhaps and can be thrown about “willy-nilly.” We need to watch that too. Mistakes and errors, whether by a reader or by a writer, can happen and do happen innocently. Evidence can be uncovered presenting a new side to an older story. That is not fake news, but rather human error and time. Discretion must be had in all directions – both in the identification of honest work and the labeling of something as fake news.

While there is no single solution to controlling this seemingly growing monster, there are two things that we can all do when engaging with any type of media. First, think more critically. If a story “makes you go hmm….”, find a second, third, or fourth source. Next, and perhaps most importantly, in our reactions to what we read and see, slow down (before you text, post, share, and tweet). If we do, so will the spread of fake news.

Sources:

[i] Combs, James E. Film Propaganda and American Politics. (1994)

[ii] Nimmo, Dan. “Political Propaganda in the Movies: A Typology.” Movies and Politics: The Dynamic Relationship ed. James E. Combs. (1993) p. 271-294.

[iii] Greene, Heather. “Political Mythology in Film: a comparative study of the Stalin myth in American and Soviet Filmmaking.” (1998)

[iv] Saunders, Frances Stonor. “Modern Art was a CIA weapon.” The Independent. (21 Oct. 1995)

[v] Baker, Gerard. “Trump, Lies, and Honest Journalism.” The Wall Street Journal (4 Jan. 2017)

[vi] McBride, Kelly. “BuzzFeed drops a Trump bombshell, irresponsibly.” Poytner (10 Jan. 2017)

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but the panic over The War of the Worlds was fake. There’s an excellent deconstruction at The Daily Beast.

I think we could handle the fake news if there wasn’t another side. Certain news reports are routinely buried or suppressed altogether. Just as one obvious example, if more people knew what the IRS was doing with non-profit applications from conservative groups, the 2012 election might have gone differently.

No it wasn’t fake. *My mother and grandmother heard that newscast and freaked out. My mother said that people were streaming into churches praying. I was shocked. I believe my mother and grandmother over anything written by The Daily Beast or those who weren’t there.

On the 75th anniversary, the Telegraph also reported that there was no panic, as did the BBC. NPR had a few pieces on it.

The Mercury Theater was up against Edgar Bergen, one of the most popular shows at the time.

My mother was THERE!

*shrugs*

I know nothing about your mother. But I know early in his career Orson Welles was a publicity hound, and pretty good at it too.

To clarify here, Welles was most definitely a publicity hound as well as a auteur that loved to play with texts, and change them in order to manipulate and challenge his audiences. That is what he was doing here. Playing with the medium and listener expectations to empower the story.

“The panic” itself wasn’t fake. It happened; it just didn’t happen to the degree that the mythology tells. (I adjusted my paragraph to clarify that point). Rather than millions in the streets, it was a few thousand and many of those people were irritated at being duped, rather than filled with dread.

It still remains a terribly interesting case of manipulation (no matter how you slice it) in media history.

I’m encouraged to see TWH alert to this problem.

I amused by term fake news. Was there ever a time when our news was honest seeking the truth, or that reporters were ever objective. Please when was this remarkable period of media history.

Certainly not back to the broadside posters of the colonial period. From the beginning of our country, publisher of the newspapers wrote from their own particular political view point. Newspapers quite openly supported one political party over the other. The public often trusted the reporter with their viewpoint, so sometimes we had better liars as reporters.

Today much of the push against alleged fake news is an attempt to stop alternate news services. After all readers and viewers lost means loss of audience, and the size of your audience determines how much the media can charge for advertising, which is what mainly supports the media.

Meanwhile do not expect honest investigative reporting against any major corporation that buys a lot of advertising in the media. Remember that 85% of the alleged news articles are little more than the media handouts given to reporters. Very few reporters have the time for, or the knowledge of how do, proper research.

❝Today much of the push against alleged fake news is an attempt to stop alternate news services.❞

Bingo.

That doesn’t mean that the alternative news is necessarily right, but there is way too much that is either readily accepted by the regular media or is allowed to slip through the cracks.

I agree, alternate news can get it wrong as well, so the same care in checking out information is necessary.

“Alternate news” is a broad term. Much of the fake news originates within alternate news sites, here and abroad. I’ve worked in journalism as a journalist, not in MSM, and the push against fake news is not strong enough.

The problem of fake news is not only one of supply, but also demand. People feel entitled not only to their own opinion, but their own facts. People today by and large don’t want to read true stories. They want to read stories which confirm what they have already decided is true.

In an ideal world, the vast array of choices and competition from MSM and infinite alternate news sites would inspire each other to excellence and accountability and would help the consumer come up with his or her most reasonably informed approximation of the truth. What has in fact happened instead is that people seal themselves in insulated bubbles which feed them only news channels or feeds which do not in any way threaten their prior uderstanding of the “truth” on any matter .Our national leadership is doing the same thing. Our democracy cannot long stand this. I hope our replacements have the dececey to take us of the barbie and shut off the grills and to bury us decently

I spent 15 years as a journalist in mainstream media. While we certainly didn’t get everything right, there was at least some standards of professionalism and accountability which simply does not exist in today’s alternate media environment. It was a profession when I entered the business.

As with anything, quality varied, but in general in the markets I worked in, you needed a Masters degree and a few years of “paying your dues” and proving yourself before you got a byline at a decent sized publication. Most of that training, and the vast majority of the day to day work was not about partisan meta-narratives of ultimate good and evil. It was about analyzing 400 page budget documents, sitting through deadly dull meetings, working the phones, knocking on doors and cultivating sources. Most of us took ethics and objectivity (or at least balance) seriously because our names and reputations were literally all we had to trade on. Fabricating sources or stories was an unforgivable sin in the business. It happened from time to time, and sometimes on the scale of the Pulitzer Prize and New York Times, but it was a career ender. As a reporter, you had to be able to produce your sources and documentation for stories, at least to your editors.

That, I think is the main difference between the so-called mainstream journalism of 10 or 20 or 30 years ago and the fake news environment of today. There was shoddy reporting and editing in the best of times, but at least in the “old days” of MSM, a reader or viewer knew that the story they were reading or viewing was reported by a real person from primary sources. There was a traceable provenance for the facts of the story and a definite, known “point of origin” for the story. Much of what passes for news these days is more akin to urban legends. Nobody seems to know where the information came from, but its widespread dissemination means it must be true.

“Outside of the framework of current politics and the recent SHOWER of potentially incriminating evidence” “now it is exacerbated by digital media’s ease and FLUIDITY of production and distribution.” Really?

It’s absolutely GUARANTEED that any fake news story will be prefaced with a statement saying that it’s NOT a fake.

Just like this one did.

No, that’s not guaranteed.