The Tao of Craft: Fu Talismans and Casting Sigils in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition by Benebell Wen.

The Tao of Craft: Fu Talismans and Casting Sigils in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition by Benebell Wen.

Published by North Atlantic Books (600 pages)

The Tao of Craft, by Benebell Wen (also author of Holistic Tarot), is an English-language practitioner’s guide to Chinese 符 (fú). 符 is usually translated as “talisman,” but Wen chooses to use the word “sigil,” which more specifically captures the use of written texts and glyphs and symbols, the ritual charging of such designs, and their relationship to both spirit-work and directly achieving desired practical results.

Wen also chooses to use the term “craft” rather than “magic.” The lines between “magic” and “religion” have always been blurry, and while she acknowledges that the vast web of traditions comprising Daoism is often religious, Wen argues that the metaphysical principles underlying the Fú techniques themselves can work from a variety of religious frameworks. Since “magic” has acquired a more diffuse meaning in phrases such as “magical thinking,” “craft” more precisely emphasizes the importance of technique and practice. Wen herself chooses to retain the religious language of Buddhism and Daoism in her personal practice, while also seeking to understand the underlying principles.

I have not had the time to craft and use any Fú sigils with the guidance of this book, which naturally limits the utility of this review for practitioners, though Wen primarily intends the book to teach theory rather than specific methodologies (instructions for crafting sigils are indeed included, however). Nonetheless, the question of cultural context and interchangeability of techniques is an important one to consider even before using the techniques themselves. Wen is of Taiwanese descent and devotes an entire chapter to “A Historic and Cultural Context,” but her familiarity with Chinese culture suffuses the entire book.

Within the broad array of Chinese ontological perspectives, Wen subscribes to the framework of 阴 (yīn) and 阳 (yáng) rather than that of benevolent and malevolent spirits, though the two are interrelated: for example, the “Classics of the Esoteric Talisman,” dating from the Tang Dynasty (618-907 C.E.) though speculated to have originated much earlier, states that benevolent and celestial spirits are summoned through “triggering mechanisms” utilizing yáng energy, while ghosts and demons are summoned through yīn energy.

While I certainly agree with Wen that certain magical techniques work across cultures, I also hold that many techniques are empowered through personal relationships to spirits or deities or other powers that assist with the work. The first thing I did when I got the book was go to the index and find and copy the Fú sigil invoking the Guan Dao, the weapon of the god Guan Di, to whom I am oathed first and foremost.

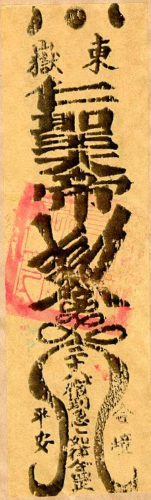

A Daoist Fú Sigil. [Public Domain]

One of the first precepts of the Classics of the Esoteric Talisman is for the practitioner to align themselves with heaven: in most Daoist magical lineages, there would be a specific deity or deities affiliated with that lineage, but Wen allows for the possibility of aligning with the Dao itself or with “a higher consciousness.” Whoever the deity or power may be, she writes, “that sense of greater alignment is imperative to craft.” This necessity is often reflected in the methodology itself.

One traditional method of using a Fú sigil, as found in a traditional spell for attaining money invoking the wealth god Zhao Gong Ming (another deity I worship daily in my personal practice), involves burning the paper, mixing the ashes with wine and drinking the resulting concoction. And as I was also taught, even after performing the spell, “one of the caveats to blessings from Zhao Gong Ming is that the recipient of his blessings must work hard and live a diligent, modest life.” Thus, in this case, magic is not a substitute for religious devotion, but a supplement to it.

The Tao of Craft is itself a well-crafted and well-researched (with copious end notes) book, clearly grounded in personal experience and practice and rooted in Chinese culture. Practitioners of all manner of magical and/or religious traditions would do well to follow Wen’s example, especially if they are considering incorporating any Chinese spirit-work or magical technologies into their work. Respect for the tradition and the spirits and powers of the tradition is crucial.

To this effect, Wen includes an excellent chapter on cultural appropriation. Wen acknowledges that certain sects believe that “only an ordained priest or priestess of a recognized Taoist lineage can craft a Fu sigil,” but the truth is that there is no real enforcement within Chinese communities about this question either: fraud and corruption are problems, though of course this is no excuse or justification for non-Chinese individuals to commit their own thefts. On the topic of cultural appropriation, Wen writes:

Crafting Fu sigils within the context of any serious magical tradition is not cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation happens if the Fu is treated as decorative ornamentation or if the practice is not regarded with the same veneration a practitioner would treat similar practices in his or her own tradition.

If one is not practicing a serious tradition that treats its practices with veneration, that might be something to rectify before intruding into the traditions of others, especially given the historical context of Western imperialism and colonialism.

Wen also includes an extremely personal reflection on the question of authenticity, the question of if she, as an Asian-American, is “Asian enough” to write such a book. To be honest, I asked myself similar questions after agreeing to write this review. Wen offers the useful reminder that “esoteric texts are simply that—esoteric. Full literacy didn’t help much if you weren’t coming from a background rooted in craft.”

Wen’s familiarity with Western occult traditions, then, gives her certain advantages in her own work with Fú sigils, just as her (and my) linguistic limitations bring obvious disadvantages. The essence of craft, Wen argues, is not in copying the designs of other practitioners and traditions, but carefully thinking “about how you will apply metaphysical principles and laws to best manifest your intentions,” while demonstrating reverence for divine and human and non-human relationships.

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Pingback: TWH Book Review: The Tao of Craft | Heathen Chinese