TWH – In 1994, three student filmmakers walked off into the dense woods near Burkettsville, Maryland in hopes of a discovering the truth behind a local legend. They were never heard from again. One year later, their equipment was found, and the footage became the film The Blair Witch Project (1999). This weekend, the story continues in a new film, with the brother of one of the lost filmmakers traveling to the mysterious Black Hills of Maryland in hopes of learning exactly what happened 22 years ago.

Or so the story goes.

While the Blair Witch project did begin in earnest 1994, the entire film venture is manufactured, including the plot, the legend, the town, the footage, and even the made-for-television, promotional mockumentary, titled Curse of the Blair Witch (1999). Directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, The Blair Witch Project was an indie success, a technical novelty, and a marker of its time. According to a Fortune magazine article, the film cost $60,000 to make, and earned $1.5 million at the box office on the first weekend, while only in 27 theaters. [i]

Outside of the early buzz created by the SyFy Channel’s pre-release of the mockumentry, The Blair Witch Project captured the imagination of a viewership already engrossed with supernatural or paranormal entertainment vehicles (e.g., X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, So Weird, Ancient Mysteries). In addition, new technology was quickly eliminating barriers to indie filmmaking, making the film’s concept very possible.

This new digital medium, far more than its analog counterpart, also increasingly allowed for the construction and the reconstruction of recorded reality, leaving much room for the manipulation of our nonfictional storytelling. What is real and what has been falsified? Can we trust what we see in photos and film? In that way, The Blair Witch Project at its very essence captured not only its own time, but also what was to come. It seemed to be a doorway into the new millennium of how we tell our stories.

The breakout success of the original Blair Witch Project led to a 2000 sequel, titled Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, which was directed by Joe Berlinger. However, the sequel, costing $10 million, was unsuccessful, failing to capture the original’s grit or poignancy. Hard-core fans and reviewers often remark that they would simply like to forget that the second film even happened. In 2000, New York Times reviewer Stephen Holden had some kinder words for the film, but added, “For all its clever notions, ‘Book of Shadows’ often seems more like a montage of pasted-together images than a coherent horror story.” [ii]

With the end of the witch film cycle at hand and the poor showing of the second film, this seemed to be the end for The Blair Witch Project. However, in 2016, as witch films have made a return to the screen, so has the Blair Witch.

Before going forward, this review will discuss some, not all, details of the new film. If you haven’t seen it, you can stop here. However, with that said, neither The Blair Witch Project nor Blair Witch are heavily dependent on plot elements for enjoyment. In other words, even if you know what is going to happen, your viewing experience won’t necessarily be spoiled. Both films operate as journeys, and the tension is created in the process and not the story itself. It is analogous to riding a roller coaster. No matter how many times, or in what detail, a friend tells you about roller coaster, the experience of riding can never be spoiled. That is how both The Blair Witch Project and Blair Witch work.

In this new film, Jason, the brother of lost filmmaker Heather, seeks to find the truth of what happened in 1994. He is accompanied by a friend and indie filmmaker Lisa, his best friend Peter and Peter’s girlfriend, Ashley. When arriving in Burkettsville, Maryland, the group meets up with locals Lane and Talia, who accompany them into the woods. From there the search begins.

Directed by Adam Wingard and written by Simon Barrett, Blair Witch (2016) is structured identically to the original. It is more of the same, from character introductions, through equipment gathering and travel, to the trek into the woods. Once in the Black Hills, like its predecessor, the film progresses through a slow buildup of a tension, making use of the film’s medium and documentary approach (e.g., extreme close-ups, quick cuts, movement, and point of view).

In many ways, it’s a repeat with new characters and contemporary technology. And like the original, we are trapped in the cameras, which for this film have been increased in number. This visual claustrophobia mirrors the characters’ mounting fears. You might find yourself frustrated and tense, asking, “What is going on?” While it serves the purpose well for most of the film, there are points where it becomes a detriment.

But as much as Blair Witch mirrors its parent, the two are not the same. The new film spends less time focused on the investigation, or legend-tripping, and more time enjoying the horror. The original film worked through a slow buildup to its end. The new film jumps quickly into its terror points, moving ever faster from one to other and slowing down only to enjoy itself once there. For example, the narrative stops fully to indulge in the removal of a wound’s bandage, emphasizing the experience of disgust with the heightened sound of what seems to be wound and ooze.

Additionally, Blair Witch makes a few interesting attempts at layered characterizations, moreso than the original. For example, when the four friends enter Lane and Talia’s living room, they find a confederate flag hangs on the wall. From presumably Jason’s camera view, we watch Peter, who is black, look at the flag and then turn back to the camera. His disgusted expression is poignant and unmistakable. Minutes later the four are outside and Jason asks whether they should take Lane and Talia on the trek. Without a pause, Peter says emphatically, “No,” and his facial expression once again says it all. Unfortunately, the film abandons these clever indulgences in characterization as soon as it takes up its horror role.

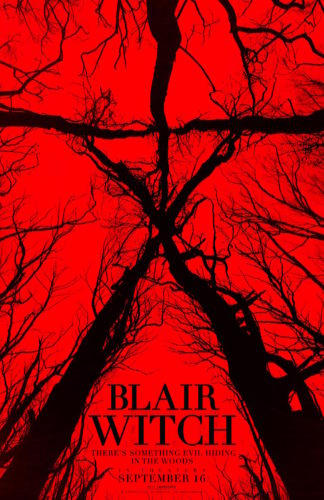

Lionsgate “Blair Witch” (2016)

But what about the Blair Witch herself? This is another point where the film deviates from its parent. As noted earlier, the original narrative was presented as a legend-tripping experience, with the object of fear being only an archetype that lives within our collective culture consciousness. She is the Baba Yaga figure, the monster in the woods. But is she real? The first film leaves that answer to the imagination.

Blair Witch moves in a different direction, offering viewers an answer to that very question. There is in fact an object. There is a monster. Although it is not visually made clear, this thing in the woods is called the Blair Witch and gendered as female. “Don’t look at her directly and she won’t hurt you,” says Lisa. With that definition, the monster becomes, in earnest, the old woman in the woods, a symbol of primal fear and that which is unattainable and wild. The new film leaves no question as to the existence of the monster.

This age-old archetype of Baba Yaga or the wild woman in the woods pervades American witch films across the decades. Woman’s power is equated to that which is naturally wild and uncontrollably dangerous. In Orson Welles’ Macbeth (1948), the influence of the weird sisters and that Lady Macbeth are visually juxtaposed to leafless trees, storms, rocks and night sky. In the 1987 film, The Witches of Eastwick (1987), the devil, portrayed by Jack Nicholson, angrily asks a congregation if God made a mistake when creating woman. Then he says, “When we make a mistake, it’s called evil. When God makes a mistake it’s called nature.” But even more recently, Roger Eggers’ The Witch uses the very Baba Yaga archetype found in Blair Witch as a counter to the severity of social control present in early Puritan America. In these examples, woman is nature, and nature is magic, and it is all uncontrollable.

While the story is pervasive in western society, it doesn’t always sit well with modern Witchcraft practitioners due chiefly to the religious implications placed on it by Christian theology. In fact, Berlinger’s Book of Shadows included Erica, a Wiccan character who was unhappy with the first film’s portrayal of the witch.

In reality, modern Witches have had a mixed response to the Blair Witch films, as often is the case. In 1999, blogger Peg Aloi spoke with directors Myrick and Sánchez about the archetype. Myrick said, “We never meant to say anything bad about Witches in general.” The use of the witch was just a reason to “get the kids out there.” It was a plot device or what Myrick called “a triggering mechanism.” The original film was essentially mimicking the popular teenage legend-tripping experience, which can be horrifying in and of itself. As Sanchez remarks, “It has nothing to do with witches.”[iii]

The original directors were, in fact, very conscious of modern Paganism. They included a bit on Wicca in their promotional mockumentary. Among the other “footage,” they inter-spliced segments from a fake 1971 film called “Mystic Experiences.” Aside from its use of the term Wiccanism as a name for the religion, this segment, which allegedly featured a real Witch, is as authentic feeling as any other piece of the mockumentary.

Still From: The Blair Witch Project (1999)

However, as noted earlier, the new Blair Witch takes the archetype into a different place, well beyond the surreal experience of legends, ghost stories, and the imagination. Here, although mostly visually obscured, “the witch” is a real object of some kind. This monster is not derived simply in the mind, from centuries of legends and a collective fear of the woods. It is there. It is real, and it is described to us, through the characters and their collective cultural understanding, as being female.

While the film’s many embedded traditional horror elements, like this manifested monster, may bother some fans, the new film could not have functioned in the same way as the original. Part of its success was in the confusion as to what aspects of the story were real, and what were constructed. The suggestion of reality added to the original’s terror.

Now we know the story.

For a successful 2016 reboot, Blair Witch needed to find a new terror device to take the place of that tension. It chose classic visual and audible horror tropes, like jump-moments, gore, bodies, intense sounds, thunderstorms, tight shots, obscured imagery, and a very classic manifested horror monster.

The new story is about the witch, and it will continue to be so if there is another journey. The franchise has no choice…for better or worse.

While the many classic horror details are not, in and of themselves, disappointing or distracting, they do give Blair Witch a different feel and speed than the original film. Hard core fans, as noted earlier, might be disappointed with that shift. For others, it may be a plus.

No, Blair Witch does not (and could not) have the technological ingenuity of the original, and it will not hold the same cultural significance. However, despite any flaws and differences, it is a well-structured horror film that moves through its thin story and delivers on entertainment. Many viewers will enjoy going back to the Black Hills again in search for the truth, which in the end is apparently out there.

* * *

[i] Carvell, Tim. “How The Blair Witch Project Built Up So Much Buzz Movie Moguldom on a Shoestring.” Fortune Magazine. (Aug. 16, 1999)

[ii] Holden, Stephen. “Burkittsville Revisited, With More Mind Games.” Rev. of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2. Dir. Joe Berlinger. New York Times (Oct 27, 2000)

[iii] Aloi, Peg. “Blair Witch Project: an interview with directors.” Witchvox, (July 11, 1999)

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Disappointed that the film took the direction in did in regards to the monster. Really enjoyed how the original film left it to the imagination, let people create theories. My personal favorite is that Heather’s crew actually led her to the woods to kill her

I loved the first one and was a Christian when it came out. I watch these now with a different eye but still try to keep them fun and not commentaries in those of us who actually practice. I like the idea that witches are still seen as unruly and separate to an extent. That we are still see as tied to nature and the chaos and untamed aspect of it. Witches are like werewolves and ghost at this point as far as movies go. I doubt that will ever change.

I really hope the new film is better than the original – but it couldn’t possibly be worse. I never saw where the supposed $60K was spent on the original, it could have been filmed by a $500 camcorder of the day, just as it was supposed to look like – never mind that it was just a bad film from the get-go. Not a fan, obviously.