I recently stumbled upon three unrelated articles examining new ways of combining technology and religion. The first reports on a robot Buddhist monk, the second asks if apps believe in God, and the third promotes the use of computer models to study religion. The articles aren’t actually as unrelated as they first appear. In each case, the use of current technology serves to create an artificial distance between the twenty-first century (schizoid) man and the spiritual, in whatever form it may take. The focus is on reducing the poetic and unquantifiable experience of religion to prosaic and measurable object that can easily be filed away as just one more manufactured moment in our digital lives.

A Robot Monk

The New York Times’ Didi Kirsten Tatlow reports on “the world’s first robot monk,” a two-foot-tall device modeled on a character from a Buddhist comic book. Named “Worthy Stupid Robot Monk,” it was designed and built by Beijing’s Dragon Spring Temple and a consortium of approximately twelve Chinese culture, investment, and technology companies. Looking like a bald monk in a saffron-colored robe, the apparatus holds a touch-pad that allows visitors to the temple to enter questions and statements that are then answered.

![“Worthy Stupid Robot Monk” of Beijing’s Dragon Spring Temple [Photo Credit: http://eng.longquanzs.org]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/201605221213010-500x316.jpg)

“Worthy Stupid Robot Monk” of Beijing’s Dragon Spring Temple [Photo Credit: http://eng.longquanzs.org]

Q: What is love?

A: Love is your own obsessions not being satisfied, the clashing of other people’s troubles with yours.

Q: I want to die.

A: Don’t assume you’re the most pathetic person in the world.

Q: Could there be another Cultural Revolution?

A: Wait, I will ask my master.

The article’s title states that the robot is “mixing spirituality with artificial intelligence.” The concept of AI is regularly invoked in popular media posts dealing with everything from Hello Barbie to smooching. Most of the time, the concept of AI is a clickbait stand-in for “thing that responds to input by producing output.” Any device or program with even the most basic responsive algorithm can lead to a journalist on a deadline to write a breathless post about the coming rise of the machines.

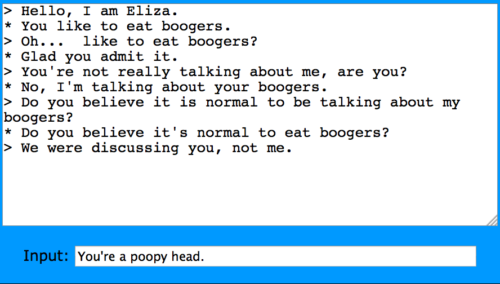

Take another look at the exchanges with the robot monk. The first question causes the device to produce a definition from its database. The second includes a keyword that triggers a prepared response. The third broaches a subject outside the programming of the robot and causes a deflecting non-answer to appear. This type of simulated interaction is strongly reminiscent of ELIZA, the 1960s computer program parodying a psychotherapy session that became widely known in a BASIC version of the late 1970s.

As a child in the early 1980s, I took ELIZA for a game and played it on a dumb terminal connected to Loyola University’s mainframe computer via a dialup modem. Even as a primary school student, it quickly became apparent to me that the virtual therapist’s answers were drawn from a limited pool of responses triggered by certain keywords in my questions, and that any unexpected input would draw stock evasions.

A computer simulation of one of my sessions with ELIZA, c. 1980 [Via www.manifestation.com/neurotoys/eliza.php3]

The monk project assumes that there are simple answers to the great questions that religions have asked throughout human history. It assumes that the job of a monk or other religious leader is to provide unthinking stock responses. This is unflattering to both the believer and the monk, for it sees each of them as a simple creature unable to wrestle with the complexities of the questions that religion struggles to answer – and it misses that this very struggle is at the core of the religious experience.

Siri’s Bat Mitzvah

The How We Get to Next website asks “Does Siri Believe in God?” and writer Leigh Alexander provides “A theological guide to chatbots and the world’s major religions.” Although the post generates the usual gagging reaction triggered by the tired trope of “the world’s major religions” (here, as always, the three Abrahamic traditions with Buddhism added for “inclusiveness”), it also provides an interesting insight into the way a young twenty-first century woman views the abandoned religion of her childhood – and how that view informs her conclusions on the intersection of technology and religion.

![[Public Domain]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/368px-Alexander_Graham_Telephone_in_Newyork-e1466794506443.jpg)

“Mr. Watson, come here. I want to know if you believe in God.” [Public Domain]

After a dialogue with a computer scientist at UC Berkeley’s Center for Jewish Studies, Alexander concludes that “it would be most in line with Jewish thinking” to welcome a robot as a practicing member of the religious community. After having similar interactions with a Muslim video game designer, a Christian science writer, and a cognitive scientist – and reading a blog post by a Buddhist (an unfortunate lack of personal engagement with the one non-Abrahamic tradition included) – she offers a somewhat standard conclusion for these types of articles, referencing Asimov’s 1942 laws of robotics while warning against the coming rise of the machines.

Alexander’s piece is interesting and insightful, but it also exemplifies the intersection of post-religious identity with today’s personal technology. My own unverified personal gnosis generated by my wizard eye tells me that the most vocal supporters of the “new atheism” are those who were raised in earnestly-believing monotheist families. For some, it seems that the fact that their only religious experience was during the time of their life when their will was subjugated to the wishes of their parents has led to an understanding of religion that is mired in a childhood worldview of seemingly capricious rules and regulations. A similar view of Christianity is especially common among Pagans and Heathens who converted into their current tradition after conservative Christian childhoods.

Such a perspective on religious experience is a natural fit with an embrace of technology as a metaphor for spirituality. Alexander’s reflection on the rituals of her Jewish childhood as rule-bound training devoid of spiritual meaning unsurprisingly leads to a conclusion that an app or robot powered by if/then programming is fully capable of participating in religious community. As with the acceptance of a cartoonish robot as something that can fulfill the complex role of a monk, the idea that a cell phone app can be a contributing member of a religious community brushes aside the deep and complex human experiences and interactions that comprise what we call the spiritual and the religious.

Replicant Believers

A random tweet led me to the website of the Institute for the Bio-Cultural Study of Religion’s Simulating Religion Project. The anonymous article introducing the project summarizes its ultimate goal: “If the Simulating Religion Project (SRP) succeeds, when questions about religion’s social functions arise, scientists can answer, ‘There’s an app for that,” with app defined as “a simulation program.” In other words, the SRP “aims to develop software that will simulate the cognitive-emotional mental processes and social interactions that mediate the effects of religion on social and cultural systems.”

“Somewhere in here, we’ll find the gods.” [Still from “Manchester Baby.”]

Note that the final statement suggests that religious studies must be simplified in order to deal with the inherent limitations of computer modeling, rather than calling for computer modeling to be developed that can handle the complexities of religious studies. While acknowledging the limitations of previous attempts to create synthetic models of human religious behavior, the writer seems profoundly troubled by the complexity of data generated by the study of religion:

Past simulation research in religion has grossly oversimplified the way humans interact, think, behave (especially morally), and change; this, obviously, will not do. At the same time, one should not include too much complexity in the simulation because this risks obscuring the issue rather than clarifying it. Too much simplicity gives wrong answers, and too much complexity gives unclear and confused ones.

On the website’s Modeling Religion Project Portal, the stated goals include production of “a simulation development platform that will allow SSR scholars and students to create complex simulations with no programming” and “a series of simulations of the role of religion in key transformations of human civilization, such as the Agricultural Transition (c. 8000 BCE), the Axial age (c. 800-200 BCE), and modernity (c. 1600-2100).”

There’s a lot to unpack here.

The spirit of Dr. Asimov is again invoked, if not by name, as the SRP seeks to create analytical models of human religious history from 8000 BCE to 2100 CE – from the ancient to the future – along the lines of the fictional Hari Seldon’s psychohistory, “that branch of mathematics which deals with the reactions of human conglomerates to fixed social and economic stimuli.” Creating any sort of model of religious cultures from 10,000 years ago involves assumptions about the knowability of incredibly ancient worldviews that would make even a reconstructionist blush, while asserting the ability of computer models to predict spiritual beliefs of those who will live nine decades in the future seems to evince a belief in the power of prophecy not so different from that of the arch-Heathen. Such an embrace of the powers of computer modeling borders on the mystical.

The pulling back from the messy complexity of religious studies is a typical reaction to the uncertainties of human experience that regularly makes an appearance in scientific communities. A friend who is a professor of engineering recently gave me a personal lecture to the effect Bernie Sanders supporters are sloppy-minded humanities folks whose emotions rule their lives while Hillary Clinton supporters are clearheaded scientists who have objectively evaluated the data. This engineering attitude seems to underlie the SRP’s belief that those who study religion are troublingly incoherent and inconsistent, and that real scientists need to get the data in shape in order to save religious studies from a state of irredeemable confusion.

This worldview is similar to the one expressed in the articles about the robot monk and the Jewish chatbot. While insisting that “too much simplicity gives wrong answers,” the SRP still embraces the idea that religious experience is something that can be reduced to a role-playing game and that believers ancient and yet unborn can be brought to digital life as non-player characters. Human existence is full of irrationality in general. Our desires, decisions, and deaths are not often algorithmic. Religious feeling is one of the least rational experiences of all, for good or ill. The idea that spirituality, of all things, is something that can modeled by computer engineers is itself irrational.

That scholarship on religion is so complex and irreducible to formula is largely due to the nature of the beast. Religious experience, across its broad spectrum and in all its variations, is not something that can be reduced to a Speak & Spell in a saffron robe, an iPhone app in a synagogue, or a computer model on a gaming table. If you want to understand religious experience and haven’t had it yourself – aside from being forced to go to Sunday school or Hebrew school – the best thing to do is to meet people from different religious traditions, get to know them, and listen to what they have to say. That’s a messy process, and it takes much more time and commitment than listening to a one-sentence answer from a robot, downloading an app, or studying replicant religionists that can be silenced with a keystroke. Many in today’s world will go to great lengths to avoid dealing with the complicated world of face-to-face human interaction. That’s not something to be celebrated as progress.

[Editorial Note: The Robbie the Robot photo that was previously in this article and is still being used in social media in connection with this article was used taken by DJ on Flickr]

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Okay, so the first picture of the robot is obviously from the 1950s movie, Forbidden Planet, later used in the 1960s TV series Lost in Space where it was renamed “Robbie”. It certainly wasn’t the “robot monk” that I saw in the same article you must have read.

Personally, I think humans are waaayyy to complicated for a program to figure out. AI is in its infancy and I don’t think it will reach maturity for a long time to come. Hopefully by then the human race will also have matured considerably. 🙂

As much as we adore Robbie the Robot, we were able to find a usable photo of the robot monk and have changed the image accordingly to avoid any further confusion. Thanks for reading and commenting.

Re: If 2016 robot monks are really running the same basic software as a 1966 computer therapist – or, at least, the same concept of interaction is serving as a model for its programmers – are we really that much closer to HAL 9000?

Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do…

In some ways, Dr. A was ahead of his time, even if he was completely mystified by women.

re: Note that the final statement suggests that religious studies must be simplified in order to deal with the inherent limitations of computer modeling, rather than calling for computer modeling to be developed that can handle the complexities of religious studies.

I agree. Sorry, can’t simplify the religions, much less the studies thereof, O Engineer.

Most religions are Mystery-based–can’t adequately describe the experience to those who’ve never had anything like, and for those who have, no words are necessary, that old chestnut.

In Lois McMaster Bujold’s world of the Five Gods (although some in that world are merely Quadrenes, ignoring the Fifth God), the second novella of Penric and his “demon” Desdemona, a lot of information about the interactions of those Five with humanity is passed along, and what happens, or can occasionally happen to the soul after death is discussed.

In the first novella, Penric unexpectedly and out of the usual way, acquires the collective twelve personalities that held this demon, when their last host suddenly dies, and Penric has stopped on the way to his marriage of convenience wedding, attracting said demon’s attention and consent to transfer to him.

Instead of screaming bloody murder and fighting the sudden intrusion, he continues as polite as ever, something Desdemona (his name for them) has rarely experienced in a host. That’s awfully similar to how I handled a Visitor in the middle of a dance routine, where I was portraying her.

There are discussions of what Saints are, what Divines are, what kinds of shamans and what they do, and the interactions of the Deities with humans, in what they can and cannot make happen in the physical world.

That’s darned hard to simplify, just as our experiences as Pagans, Heathens, and Polytheists are. I don’t care that there is a region in the brain, which if stimulated in a medical situation, results in something close to a religious/spiritual event.

I deny that being the whole of our spiritual being and activities, nor that what we feel, experience, and believe is *merely* brain cells being stimulated, and that our Deities are manufactured merely out of neural stimulation. I reject that with all of my soul.

So if I can’t simplify what I’ve experienced, how can some set of computer modelling, devised by those with perhaps no experience of spiritual matters, define me and my experiences?

That what we experience is by way of brain cell activity does not deny the experience itself, any more than an understanding of the retina disproves the existence of rainbows.This will not be resolved until engineers produce computers complex enough that they don’t need to request a simplification of what they are trying to model. (Of course, should such a computer report an epiphanal experience of its own, then the conversation really gets interesting…)

Pingback: Modeling Religion Project Outreach – Human Simulation