I.

If determined enough, the dead can assert themselves to appear nearly as present as the living.

And if one who is noticing and interacting with them does not know they are dead, and/or they are too young to comprehend what dead even is, the distinction between dead and living becomes rather confusing if not at times completely irrelevant.

This was my experience, anyway.

What I believe to be my earliest memory, for example, seems quite average on its surface.

I am a toddler, just old enough to walk and talk. My grandparents are sitting up in their bed, facing the television that was perched on their dresser, and I am sitting at the end of their bed, playing with a pile of coins, babbling enthusiastically to my grandpa about my stacks of pennies. On the television is a rerun of ‘Matlock’, and my grandpa is engrossed in the show, not paying much attention to me. But my grandmother keeps reaching her hands out toward me, trying to get me to sit on her lap. And I keep looking over at her and smiling at her, but I am too distracted by stacking pennies and the sound of my own voice to go to her.

Me at 2 1/2 in the yard where I sometimes saw my grandmother.

It’s a notably clear memory, right down to every little detail. And it wouldn’t strike me as unusual at all if not for the fact that my grandmother died of cancer when I was only a year old, well before I was old enough to climb onto the bed and babble in sentences and recognize Andy Griffith’s face on television.

And yet nobody had told me directly that she had died, and everyone else in the house still talked about her as though she was still there. So it didn’t seem all that out-of-place to me as a toddler that I would see her around and occasionally interact with her. My clearest and most sustained memory of her is of that day in the bed, but I can also clearly recall seeing her hovered over the counter in the kitchen, sitting in one of many antique chairs in the living room, hunched over the dryer in the laundry room, sweeping on the back patio, or in the backyard near the doghouse.

Our dog also had been dead for quite some time, having been my mother’s childhood pet. The backyard had seemingly been abandoned once the dog had passed on. By the time I was a toddler, the backyard was so overgrown with ivy it was barely navigable, and the doghouse still sat in the corner, rotting and collapsing, with a metal bowl still poking out from the ivy. But just as I did not grasp that my grandmother was no longer on this plane, I similarly did not completely grasp that we did not actually have a living dog. I never saw the dog quite as I saw my grandmother, but I sensed that she was there all the same.

It wasn’t until I was around four years old that it started to occur to me that my grandmother was not a current member of our household and that my sightings of her were not shared by my mother or my grandfather. I had overheard a phone conversation in which my grandfather mentioned “the summer before Betty died.” I still didn’t understand what death was, but I could sense what it meant on one level, and it meant that the person was said to no longer be here.

And yet she was. She was all over the house.

My grandmother in the kitchen, exactly as I remember her.

II.

One afternoon not long after that, my mother and I were in our front yard, sitting on the sole boulder that graced the edge of the yard. My mother was watching the road in front of us, waiting for a friend, while I scrambled up and down and around the rock. There were etchings – crude letters carved into the side of the rock, which I had always noticed for their texture but which suddenly held a greater interest to me as I was just learning to read.

“What does it say?” I asked my mother.

“It says ‘Here Lies Elroy’, she said.

“Who’s Elroy?”

“Elroy was my brother’s gerbil.,” she explained. “When he died, Jay buried him under this rock. That was when we were kids, long before you were born. This rock is Elroy’s gravestone.”

“So Elroy is dead like Grandma?”

“Yes, and like your uncle Jay.”

All I knew about my uncle Jay up to that point was that my bedroom was once his room. In a sense, it was still his room. It was often referred to as “Jay’s room” by my mother and my grandpa, and I had always felt that, while it was my designated space within the house, on another level it was not my room at all. I had somehow always felt more like a guest in that room than its primary inhabitant. But unlike Grandma, who was talked about regularly and often as though she was still present, Jay was rarely mentioned, and I had always sensed not to ask questions about him. My room was his room, and that had been the extent of my understanding.

But now, at least I knew he was dead. And on one hand, that knowledge only deepened the mystery, but on the other hand for the first time I felt as if I had some concrete understanding about who was still here and who was not. They were all dead – Jay, Grandma, Elroy and my mother’s old dog who still seemed to live in the backyard. At at that moment the fact that they were all dead was suddenly real where before it had only been abstract.

III.

As I reached grade school age, the sightings of Grandma became much fewer and farther between. And while I couldn’t deny to myself that I was still seeing her occasionally, the part of me that knew that I wasn’t supposed to be seeing her would very actively kick into gear, resulting in a tug-o-war in my head between experience and reason every time I thought I spotted her.

‘Ghosts aren’t real’

‘But I saw her!’

Part of me didn’t want to be seeing her at all. Part of me just wanted to believe I was imagining things. And part of me also wanted to tell the world, or at least to talk to someone about it. But part of me also knew that it was very real, and that I was best off keeping my mouth shut.

And so I did keep my mouth shut about Grandma. I also knew to keep quiet about what was in the garden.

My mother had built a garden in the side yard the year before. She would sit me out in a tiny lawn chair with books-on-tape as she worked for what seemed to be hours on end, weekend after weekend, tilling and planting neat little rows of flowers and vegetables.

Within a few months, we had a glorious garden, and it quickly became a favorite spot of mine. I would spend hours out in the garden, examining flowers and bugs and stealthily rescuing/relocating the snails from the saucers of beer that my mother would leave out to drown them.

Garden slug. [Photo Credit: I. Colae]

Maybe this is God, I thought to myself more than once. But God is a man, I would then reply to myself. I knew little about religion or God, other than that my mother had referred to our family as “lapsed Catholics” when I asked her once. But I had taken enough in from the wider culture to know that ‘God’ was also the ‘Father,’ and while I couldn’t see whatever was in the garden, I felt very strongly that it was female. So she couldn’t be God.

But what was she?

I didn’t know, but she was definitely there. And I liked her, and I could tell she liked me back.

Around that same time, I had started to read the book Anne of Green Gables. In the book, Anne refers to God several times as ‘Providence,’ which stood out to me as unusual as I had thought that Providence was a female name. At some point, I was reading the book in the garden, and when I felt the presence of the yet-unnamed entity in my garden, a potential connection stirred in me.

I asked whoever was there if I could call her Providence. And I sensed immediately that the answer was yes.

IV.

When I was ten, my grandfather died.

My mother and I had moved out of the house three years earlier. She had remarried, and they were able to buy a house of their own, a small Cape Cod-style bungalow about ten miles away from what then became known as “Grandpa’s house.”

Grandpa had continued to live in ‘his’ house for the next few years until a heart attack rendered him unable to live alone, and he ended up moving in with us for what ended up to be the last few months of his life.

My grandfather, six months or so before he died.

I grudgingly surrendered my bedroom, not really grasping that his life was coming to an end. He recognized my frustration at losing my space and invited me to share the bed with him if I wished. I took him up on it a few times a week.

And it was on one of those nights, when I crawled into bed with him in the middle of the night, that he died peacefully in his sleep with me sleeping right next to him. When I woke in the morning, I turned to shake him awake, and he was cold. I knew instantly that he was dead.

After the wake and the funeral were over, what remained to be reckoned with was nearly as emotional and painful as my grandfather’s death in itself. We needed to do something with Grandpa’s house.

I had assumed when he died that we would be eventually moving back into that house. After all, not only was it bigger and nicer, and in a much better neighborhood, it was our home. My grandparents were the original owners, and both my mother and I were raised in that house. While I didn’t recognize it so distinctly at the time, I considered that house the closest thing I had to an ancestral home, and the land around it was the only piece of land with which I had ever had a real relationship. I wanted to live where I was born and raised, where Grandma and most likely now Grandpa still remained. I wanted to replant the garden where I first met Providence. I wanted to clean up the backyard and fix up the doghouse so that it was a more proper place for the dog that I sensed was still there.

My mother, on the other hand, had absolutely no desire to live in the house again. And while in retrospect I can completely understand why she felt that way, as a ten year old this decision sparked nothing but anguish, anger, and resentment on my part. I sullenly tagged along as she slowly emptied the house. At times, I flat-out refused to help, as I watched her empty it of the antique furniture with which I had grown up. She eventually put the house up for sale.

By the time prospective buyers were beginning to look at the house, it had all become so painful for me that I started to emotionally detach from the process, not able to bear the thought of losing it. During that period, I often took refuge in what was once the garden, by then overgrown with grass and weeds, crying my eyes out to Providence and anyone else who would listen. At one point, it occurred to me that in losing the house I would be losing my relationship with Providence as well, which only brought more tears.

It wasn’t until a few months after the house had been sold, as I finally started to recover from the numbness and grief associated with the entire episode, that I started to notice an occasional and familiar presence as I went about my day-to-day, unmistakably the same presence that I first met in the side garden as a child.

V.

My mother quit smoking the year I started. Ironically enough, her quitting and my starting were both directly related to the same event. She became pregnant with my sister and quit for the obvious health-related reasons. And then a few months later I started it up as a coping mechanism, wanting no part of a life with a younger sibling. I was fourteen years old and an only child, and was dreading the changes that were sure to come.

When my mother was a smoker, she occasionally kept a pack or two stashed in random places, a fact I remembered one day when I was home alone. Inspired by the idea of found treasure in the form of nicotine, I rifled up and down the sides of my mother’s dresser drawers, hoping to find that prized, half-empty pack of stale smokes.

But instead I found an old envelope in the crack of her sock drawer that had a piece of newspaper poking out of it. I generally wasn’t one to pry in such a way, but my instinct told me to look inside, and so I carefully and gingerly opened the envelope and pulled the piece of newspaper out.

It was a clipping from the local paper dated April 1982, summarizing the death of my uncle Jay. He had been killed in a car crash, having driven into a telephone pole only a few miles away from where we lived. The article stated that alcohol was a probable factor in the crash.

I thought of the uncle I never knew, whose room I grew up in, whose death was never mentioned once throughout my entire childhood. I felt a sudden and strange relief, as a mystery that had grated on me for years had finally been answered without my having to actually ask.

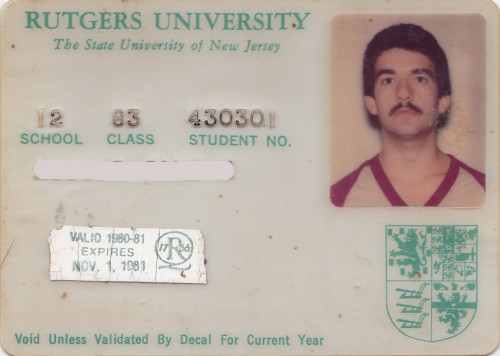

My uncle’s college ID card. He died a year before he was set to graduate.

I also immediately understood why it was never mentioned, especially given my mother’s penchant for avoiding uncomfortable subjects. And as I took in and processed this new discovery, I also forgave my mother for her silence.

VI.

I had been living on my own in the city for a year or so at that point, and had decided to drive out to Jersey to visit my parents for the day. On the drive out, my mind drifted to thoughts of my grandfather’s house, which I realized hadn’t seen since it was sold nearly a decade earlier. Out of curiosity, I decided to take a detour through my old neighborhood before heading to my parents’ house.

I parked on the street and stepped out of the car, and the moment I stepped onto the property I felt a distinct chill. Instantly, this place and I recognized and remembered each other despite many years of absence. The yard and the house had both been altered with much of the original flora removed, but Elroy’s rock remained as did the tree I planted as a small child. I walked toward the side yard, toward the garden where I first met Providence. The garden was gone.

“Hey, what you doing?” I heard a voice yell behind me. I turned around and found myself face to face with my former next-door neighbor, whose expression went quickly from anger to a smile as he recognized me. I knew him quite well; he and his wife had lived next door to our family since my mother was a small child. My mother grew up playing with their daughter, and I grew up playing with their granddaughter.

“Oh my God you’re all grown up. Look at you. I knew you’d come back one day.”

Without exactly knowing why, I burst into tears.

He reached over to hug me. “You know,” he said, as I tried to calm down. “Maureen talks to your grandpa and grandma constantly. She sees them all the time.”

I immediately stopped crying and jerked back in shock. Maureen was his wife.

“She does?”

He nodded. “Oh yes. Her and Betty have long conversations. I don’t know the details, but she says they’re both quite loud and active.”

I spoke before realizing I was speaking, before realizing that I had never said what I was about to say aloud before.

“I used to see Grandma all the time. She even tried to play with me once. I remember it quite clearly.”

He nodded again and pointed to the house. “Since your mother sold it, its changed hands three times in eight years. I swear, your grandparents are so loud over there that nobody wants to stay for long. The last folks remodeled the entire kitchen and patio before they left… I watched them just pour thousands into it but then just pick up suddenly and leave anyway.”

I thought of Grandma in the kitchen, and suddenly it all became a little too much.

I explained to him that I was on my way to see my mother and that I had just taken a quick detour and should be going.

“Come back anytime,” he said as I quickly walked towards my car. “I’m sure Maureen would love to see you.”

* * *

“I went by Grandpa’s house today,” I casually mentioned over dinner.

My mother looked up immediately. “Oh yeah?” she asked. “Does it still look the same?”

“Not really,” I answered, uninterested in talking about the aesthetic changes. “But I saw Bill. And he told me that Maureen talks to Grandma and Grandpa all the time.”

My mother laughed a bit and then was silent for a moment. “Somehow that doesn’t surprise me. Its funny, I always felt like Mom had never quite left that house.”

I stared at her for a moment, not quite believing what I just heard. Until that moment, my mother had never acknowledged anything of the sort to me, had never given any indication that she ever sensed the presence of anything at that house. Suddenly, between Bill’s words earlier and my mother’s words just then, my experiences were validated after nearly a lifetime’s worth of questioning in silence.

“She never left, Mom, trust me. She definitely never left.”

Still stuck on the idea that my mother held any kind of religious belief or superstition, I decided to go all or nothing and ask one of those questions I had never before dared to utter.

“Why are we lapsed Catholics as opposed to regular Catholics?” I asked.

It was almost as though she was expecting the question. “Well, your Grandpa’s mother, your great-grandmother, she drowned in the ocean when your Grandpa was a teenager. And even though she drowned, the Church insisted it was a suicide, and they refused to grant her a Catholic burial.” She paused.

“And then they turned around and said they would bury her for a price. Which the family somehow paid, but once she was buried the family didn’t want to have much to do with the church after that. And so neither do we.”

I had never really thought much about my grandfather’s life growing up, other than the knowledge that he had lived through the Depression. But something hit me hard the moment that my mother told me that my great-grandmother had drowned in the ocean. Our family had spent nearly every summer at the beach as I was growing up, a yearly trip which I always dreaded due to a lifelong and unwavering discomfort of being in the ocean. I could never fully enjoy the water no matter how hard I tried and I could never quite understand why, and I couldn’t help but to reflect on that discomfort in light of what I had just learned.

“What was her name?” I asked. “My great-grandmother, I mean.”

“Her name was Providence,” my mother answered.

VII.

A friend and I had spent the day endlessly talking and catching up, and trying to plan out the pilgrimage that we would be taking in just a few months. Both of us were under a lot of stress, both coming off of traumatic experiences, trying to piece together what had happened with our lives and what was being triggered by our upcoming journey. After hours and hours of back and forth, he eventually passed out on the couch. I passed out in my bed not long after, and slept better than I had in weeks.

And when I woke up, I felt a strange familiar presence, which I noted but didn’t put much thought into until he woke up a few hours later.

“I felt so safe,” he told me. “Safer than I had in ages. And I actually slept. And when I woke up early this morning, I heard this lovely voice telling me that I could go back to sleep, that it was safe. And I did. And I feel so well-rested. And whoever that was, it was such a wonderful feeling. Do you know who or what that was?”

I thought back to the presence I sensed when I woke up and I smiled. “Yes,” I said. “I’m pretty sure that was Providence.”

“Who’s Providence?” he asked.

“I’m not exactly sure,” I admitted. “I once thought she was a land spirit, or more specifically a garden spirit, nowadays I think she might be an ancestor spirit but again I’m just not sure. What I know is that she’s been around me since I was very small and she’s always nurtured and protected me. She’s just… around. I don’t think about her for a long while and then she’s just there and reminds me she exists. I’ve never seen her, but I feel her and I hear her and that’s been a constant for most of my life. She never wants anything. She’s just around, and she’s warm and she’s wonderful.”

“Yes, she’s quite wonderful,” he said with a smile.

VIII.

I woke suddenly, not knowing why. It was the middle of the night, but I couldn’t remember anything that I was dreaming which could have stirred me awake. I sat up and looked out the window, and immediately felt the urge to be outside.

Quietly so not to wake my partner, I slipped on my shoes and my coat and went downstairs. I stepped out the front door of my building, and felt myself being pulled toward the river. A minute later, I was lying on by back on the dirt by the riverbank, suddenly overtaken by a stream of visions and messages that seemed to be pouring out directly from the full moon above me.

Full moon over Portland. [Public Domain]

I opened my eyes for a to stare at the moon, and then closed them again. This time I saw what I only can assume to be the future, with flashes and aerial scenes of myself and a dear friend backpacking over mountains as the dead stirred beneath our feet. Every step we took echoed both above and below, an echo I physically felt in my feet throughout the course of the vision.

It then morphed into darkness, and we were in a cave-like setting. And then, he is gone, and it is only I. And there she is. Not a ghost, not an ancestor, but a god.

I knew what she was about to tell me. I also knew why he had suddenly disappeared, as he had not only received this exact message from Her before, but had related it to me only a few weeks prior. There was also a small part of me that knew that if I opened my eyes at that moment, that it would all disappear, that I technically did have a split-second option to escape this moment.

But I also knew that, while I may be able to escape the first-person utterance, I didn’t get to escape its consequences. And I realized in the moment that the message, though delivered before, was incomplete in its overall meaning until now. For the words were not just about the future, but also about the past.

So I kept my eyes closed and stayed, anticipating her words.

“Do not look there, unless you’d leave.”

* * *

I returned home and back into my bed. When I fell asleep again, I deeply and vividly dreamed about the house for the first time in years.

We were all sitting at the dining room table, all having what looked like Thanksgiving dinner. And when I say all of us, I mean all of us: Grandpa, Grandma, my mother, my uncle Jay, and myself as an adult. In my sleep, straddled between worlds, we were talking and laughing and drinking wine and breaking bread without any concept of the barriers between life and death. We were just together, enjoying life, as the family that never quite was.

Even the dog was there, in the corner, patiently waiting for scraps.

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Love this….I have a Dobie mutt that still stays with us, despite the fact she died 7 years ago. I hear her collar from time to time, especially in the garage, where we kept a heater next to her bed in the winter.

A wonderful and moving story. Thank you for sharing it.

This was an amazing article. I know my Grandfather is around and caring for me. I once lived in a very old house and when I would walk in the living room, the rocking chair would be rocking (and nobody in it or the room). Thank you for writing it.

Wow. Amazing writing and a gripping story. Thanks.