Author’s note:

Last year at this time I wrote about being inside an ancient burial mound in Ireland for Winter Solstice.

If anything, this essay is the shadow of that essay.

I write it for the obscured, the displaced, and the massacred at Wounded Knee, and elsewhere, as well as all the other First Nations people whose lives and sacred sites are not honoured by Americans, Pagan or otherwise.

And this is also for Anthony.

Mound and Mountain Laid Low

I woke into world the bastard child of a slaughtering Empire. I woke into world in an old Shawnee town, but I am not Shawnee, and the town is their ghost.

The town, in Shawnee, is called Chalawgatha, which is also the name of the band of Shawnee who lived there. Wherever they settled, they settled in Chalawgatha, because they were the Chalawgatha, and so Chalawgatha was their town.

What is the ghost of their town is a sprawl of mid-western pavement called Chillicothe, Ohio.

Chillicothe sits alongside a dirtied river on the last plainslands before the land roils upward into the ancient soft-green Appalachian mountains. Chalawgatha was a small settlement upon that same river with much smaller, hand-built mounts rising from the earth. Once the Algonquin ancestors of the Shawnee traveled those time-worn mountains and buried their dead beneath raised hills. The hearts of those mountains are coal; the hearts of those mounds are bone.

It’s doubtful the Chalagawtha Shawnee suspected that one day both mount and mound would be laid low.

Reconstructed Mound City, CC BY-SA 3.0 [Courtesy Heironymous Rowe / Wikipedia]

Homes of Hillfolk Upon Open Graves

Where I woke into the world is a beautiful, haunted place, forested hills whispering ancient truths from caves and streams, wildflower-strewn vales singing fairy-tale beauty into the souls of mortals. It is also a land trashed, paved-over, blown up to get the coal from the heart of the great mountain-spirits, razed to plunder the trees clinging to their face like verdant beards.

Where I woke into this world is sometimes filmed for European documentaries on American poverty, images of shoeless dirt-faced children montaged alongside shoeless dark-skinned children in Los Angeles.

I had shoes; my neighbors did not. Water poured from our tap, my neighbors drew from an arsenic-tainted well. Our sewer overflowed and opened, feeding tree-tall grasses and milkweeds; my neighbours shat in a shed.

We were poor. Others were more poor. The race to the bottom is an abyss mirroring the race to the top, smog-filled skies reflected in sludge filled pools.

The wealthiest can always have more wealth, the poorest can always have less.

Unlike others in those European documentaries, I was never filmed. I did not know my poverty except that I was told of it on television and from my violent and abusive father, who threw crumpled beer cans against a black and white television as Ronald Reagan told us how the Union fared. Then there were the commercials for colas, and shoes, and things we could never afford but others must could, because why would the television tell people to buy things for which they had no money?

When it rained, our clay yard turned slippery, light-brown slicks pooling water into drainage ditches along the rural highway gouged through those winding hills. It was sloppy, and clay is a relentless sort of mud, but I would play for hours. I liked the world best during those rains and just after, the air finally cleansed for a few hours from the moldy garbage-smell of the paper mill along the Scioto river and the rotten sewage smell from our overfilled sewer.

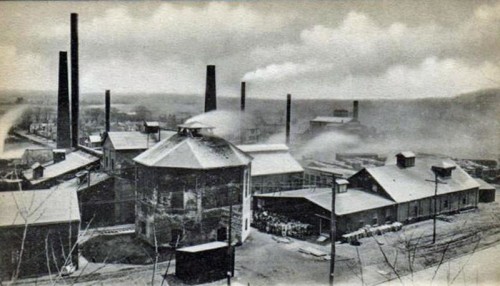

Paper Mill on Scioto river, 1901 [Public Domain]

We moderns, particularly the Pagan sort, are accused of romanticizing the past. I try not to make that mistake, but it’s difficult to imagine the slaughtered and displaced Chalagawtha Shawnee lived lives as miserable, as nasty, as brutish and as short as we’re taught to believe.

At least not until Empire came.

“Indians” like gods

I woke into the world as an ‘American,’ not as a Shawnee, a child of Empire and Capital, descended from displaced peasants from many other lands. From my father ran blood of Alsatians, Swabians, French, Irish and Welsh; from my mother came more French and Welsh and a bit of English.

I was formed from the blood and semen of peoples without title, wealth or trades. Displaced and impoverished people crafted the homunculus of me, mewling in an aluminum trailer. I was born the bastard heir of Colonialism, suckling not at the teat of imperial wealth pumps but upon rags dipped in the vats of government charity.

I knew none of this then. Empire was a thing elsewhere, wealth the currency of cities on the other side of those low mountains.

Slaughter of peoples, when you are a child, is for the story-books and the 3 channel-reception of the small glowing screen: cowboys shooting Indians, Romans burning Heathens and Christians, Hitler marching Jews to ovens. Ancient peoples and their gods were all over-ocean and under far-flung skies, not by the low mound by which I played and napped.

Ancestors from over an ocean settled in untouched forests, unwitting footsoldiers of Imperial reach, pushing the descendents of mound-builders ever westward, as if chased by an unseen, voracious monster from which all peoples knew to flee. Wars fought between the settlers’ government and the tribal confederacies always ended poorly for the defenders, but what became of these lands cannot be described as glorious or even civil.

The Chalagawtha Shawnee settled in towns nearby the burial mounds of their Algonquin ancestors. They were built during periods named in the American fashion, the Hopewell and Adena cultures, after the names of the settlers’ estates where their mounds were identified. The Chalagawtha town along the Scioto river was near a collection of mounds named now, in even more an American fashion, “Mound City.”

From that Chalagawtha near Mound City by the Scioto river came the most famous Shawnee, and the most antagonistic to Empire, Tecumseh. Traveling with his brother, a prophet given to visions of coming storms and calamities, he led a resistance of confederated Creek and Shawnee tribes against that westward push.

Tecumseh was killed in battle in 1831, far from Chalagawtha. But he would return eighty-five years later to those mounds, at least for a few years, by way of an orphaned child of settlers who went on to burn cities to the ground.

Seven years after Tecumseh’s death, Tecumseh Sherman was born, later christened “William Tecumseh Sherman” by his adoptive mother. His father, a lawyer in Lancaster, Ohio, had developed a fascination for the Shawnee hero, gifting the name to one of his children but dying without giving them anything else. Raised by a wealthy politician instead, William Tecumseh Sherman later became the general who would order “Hard War,” the scorched-earth tactic which saw Atlanta and other southern cities become settlements of flames.

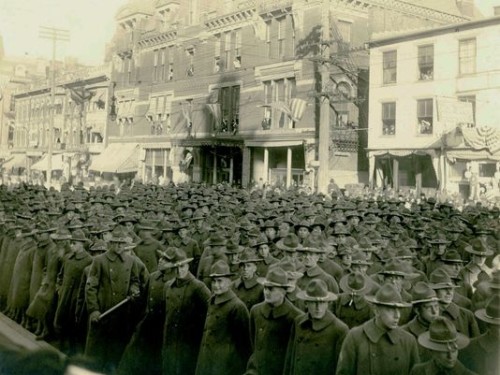

Soldiers from Camp Sherman training for the United State’s first worldwide war of Empire [Courtesy Ross County Historical Society]

Flat, except for a few small hills….

Mound City was razed to make way for global war, the birthplace of General Sherman’s namesake buried under a military fort. There, in old Chalagawtha, men trained to join an imperial power in fighting other imperial powers in trenches gouged into the land from whence the settlers who’d displaced the Shawnee came.

It’s Totemic, and also a really bad joke.

“Their graves turned into ploughed fields.”

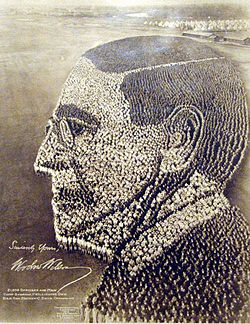

Soldiers make an image of Woodrow Wilson on an ancient burial ground, 1918 [Photograph by Mole & Thomas]

I went to the visitor center at Mound City, visited that mounded center of Chalagawtha. I remember looking at those relics, a child ten years of age, confused. There was lots of mica, some wood, a little copper, all from an age when ‘real indians’ lived and fought and died, before the coming of cities and cables.

That year—I do not remember if before or after my visit–I had learned there were still-living indians, though I could perhaps be forgiven for disbelieving it. Cable had just been lain along the ridge-line where I lived, so I’d now seen so many more stories of the killings of First Nations people that they’d become as mythic as unicorns or gods.

A real-life indian came to my school that year, dressed in white tasseled deerskin leather. I remember asking him—I had to, I’d been fooled before—if he were really an indian, because they were all dead.

He laughed, and smiled, and said ‘some of us are still alive.‘ But he looked a little sad, and very honest.

I hadn’t believed in indians, the way I hadn’t believed in gods. I’d read the stories of their existence, knew they’d once roamed the earth, but surely they’d all gone under the earth like Zeus and Apollo by now. And here was a real-life Indian, one who’d somehow survived the coming of settlers and refrigerators.

He was Choctaw, I remember. He made certain we knew this, that he wasn’t ‘from here,’ but from elsewhere.

The Choctaw were known as one of the ‘five civilized tribes’ on account of their early peace treaties and alliances with the United States. When the Chalagawtha Shawnee chief Tecumseh met with the Choctaw leaders and pleaded their help against the settlers and colonists, he was not only rebuffed but threatened by Pushmatah, the Choctaw leader, who vowed to fight those who fought against the United States.

In a transcribed speech to the Choctaw, Tecumseh warned their relationship with the new imperial state would not go well:

Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mochican, the Pocanet, and other powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man, as snow before the summer sun … Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws … Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields?

Tecumseh was right. Pushmatah, who had organized Choctaw warriors to fight against Tecumseh’s Creek alliance, died 11 years after Tecumseh in Washington D.C., there to beg the government for redress against white squatters of Choctaw land. And six years after Pushmatah’s death, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed, granting the U.S. full control over all traditional Choctaw lands, despite their decades of alliance against bellicose natives.

I do not know if the Choctaw man who spoke to our class thought much on this matter, nor did any of us children know enough to ask on that tragedy. I do know now that he was not the first ‘real-life indian’ I’d met. Adjacent the clay-pit upon which my home stood lived my friends whose always-tanned skin, even in the heart of winter, was an embarrassment to them but a matter of fascination for me. And off the ridge, in the small ghost township called Knockemstiff, lived several families without running water, whose body odor was an unfortunate source of jeer and amusement to us elementary school children; their kids shoeless except in deepest winter when they walked clumsily in adult boots many inches too big for their feet.

Angry Lands, Haunted Peoples

It’s tempting to see the re-appearance of Tecumseh to the site of his birth in the form of Camp Sherman as mere co-incidence or accidental poetry. But the dead haunt us for a reason, and if we’re to have any hope of revolt, we cannot ignore these spectres.

Besides, the United States military has an intimate relationship to the slaughtering of First Nations peoples–the same military which Pagans begged to include Pentagrams and Mjolnir on headstones was responsible for the slaughter at Wounded Knee and the countless other slaughters of indigenous folk.

Ward Churchill has shown that the ‘yellow ribbon’ to ‘support our troops’ –those jingoistic magnets on automobiles traversing highways built over the corpses of buffalo– come from the scarves worn by U.S. soldiers during the ‘Indian Wars.’ Even now, the military names weapons and military vehicles after conquered peoples (as Noam Chomsky mentions, “We might react differently if the Luftwaffe were to call its fighter planes “Jew” and “Gypsy”), and the US military code-named Osama Bin Laden, “Geronimo.”

The United States is all one vast grave of slaughtered peoples. Our subdivisions, our malls, our kindergartens and Pagan bookshops are all lain over stolen land. And not just stolen, but currently-in-the-process-of-being-stolen. I live on stolen Duwamish land–and they, whose river is a Superfund site poisoned by industry and occupied by a war-machine manufacturer, are not even recognised as a tribe despite their very real existence.

Polluted river of the Duwamish [Public Domain]

But so do we.

Our disenchantment is mere denial, springing from our separation from the land and ourselves. It’s horrifying to make a connection between the places we live and the rivers of blood and sagas of sorrow which cleared the land for our single-family homes and hipster restaurants, or even our sacred sanctuaries. This is Marx’s ‘estranged labor,’ expanded by Silvia Federici’s work, the way we separate aspects of our being, classify our activities, and Enclose certain experiences from other experiences, living disjointed, fractured existences, alienated from and terrified of interwoven threads of meaning.

Animism can shatter these categories. Paganism’s supposed to, but can’t if it continues to cling to the benefits of Empire. Animist peoples know this, but we, bastard children of Empire, do not.

Being disenchanted, utterly disassociated from the land means we can’t even trace the threads between the ‘benefits’ of modern civilization and the slaughter of peoples.

Appalachia is the World

Nowhere is this more evident than Appalachia, the place where both Tecumseh and I were born.

Much of Appalachia is what some call ‘exclusion zones,’ and they are essential for the existence of Capitalism, as well as most of what makes modern life so (-called) ‘civilized.’

In exclusion zones, Capitalism functions precisely as it did when it first started, poisoning the water and air, raping the land for resources like coal and wood, and keeping the population in conditions quite similar to early 19th century peasants. There used to be many more such places in the United States, but in the last fifty years, as environmentalism took hold and terror of acid rain, smog-filled cities, cancer, and developmental disabilities finally took hold, Capitalists altered their behavior…slightly.

They didn’t stop wasting the planet, polluting the air and water, or making miserable the lives of people. Instead, they just moved it elsewhere, hid it from the view of the consumers whose purchases give consent to all this exploitation. They moved this to exclusion zones, benefiting from (and propagating) myths about the ‘backwardness’ of the people in those areas, helped ensure those who didn’t see that damage never took seriously the accounts of people experiencing it.

Excavation and destruction of Adena mound, another sort of ‘mountain-top’ removal, 1901 (Public Domain)

Thus, in American discourse, Appalachians are stupid hicks, backwards, violent conservatives (or militants), uneducated, and not worth listening to.

And If you’ve followed anything at all about the recent protests over the murders of unarmed Black men in the United States, you’re probably seeing a parallel. The same that is said of people in exclusion zones in the United States is said of People of Color, and this is not by accident.

The plight of the Appalachian whose water is poisoned by coal mining is similar to the Midwesterner whose water is poisoned by fracking, and both are similar again to the plight of the Black family living in Detroit or Baltimore in abject poverty, with their water being turned off. And the similarities don’t end there–lack of resources, lack of education, high crime rates, indifferent and often oppressive government representatives, and a great silencing of their voices constructed through prejudices regarding education, lifestyle, culture, and family structures.

And these groups are all similar to those living in exclusion zones around the world, where the overwhelming amount of damage and destruction wrought by Capitalism is displaced. Razed forests, poisoned rivers, dried-up wells, toxic waste, abject poverty, unbreathable air–these are the foul spirits birthed by Capitalist greed, but we don’t see it.

The same process which keeps us from seeing the Dead, the spirits, the fae, and the gods keeps us from seeing the Chlnese labourer attempting to kill herself rather than make another iPad, from seeing the connection between our automobiles and U.S. Imperialism, our electricity and mountain-top removal, our comfortable lives and the constant wars in the Middle East.

It feels like we’re waiting for an inheritance we’ll never get and we are not owed. Empire’s slaughter cleared land for the coming of displaced Europeans like my own family, but it doesn’t care about me, only my submission, only my silence.

It also doesn’t care about you, either, except that you buy what it’s got to sell, stare at screens on your way to your jobs, and keep denying the connections between your security and all the people that have to die to make you feel safe.

The dead Black kid in the street is also the slaughtered Lakota at Wounded Knee, and they are both also the drowned Syrian refugee, the shoeless cancer-ridden Appalachian, and all die in the name of Empire.

Perhaps we, Empire’s bastard children, will finally take their side instead.

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I agree with all of this without reservation.

So some questions that need answering then:

What would you have us do?

What do you think can wake the sleepers and convince them to work together to overthrow this Empire?

What would replace it?

Do you think there are answers to these questions which can convince most people across the world, across all significant demographic populations, to actually fight this system?

We are programmed to buy and to want and to ignore the suffering this causes others or to offer token resistance of “giving to help others” which only helps us hide and ignore the symptoms of the greater problem. How do we wake ourselves up from that and stop ourselves from participating? Once we do that, can we convince others?

These questions need answers before we all willingly help to kill the Earth, the Spirits, and our own souls.

We can only awake ourselves and do differently to be an example to others. Show them, don’t tell them.

A startlingly profound, raw, and visionary piece of writing. You are right, Rhyd, in all that you say. Empire arises from sacrifice; but sacrifice without bounds or consent – the unholiest of rites.

Uncompromising and true.

So very sad and so very true, to the rich there is nothing more important than staying rich and getting richer. We need to do away with kings and rich people everywhere, let those who break their backs to make the rich richer have control.

And now the white man will become a minority and he is scared that he will be treated as he has treated others around. That may well happen, and when it happens, the innocent are more likely to bear the brunt of the pain and suffering, that was also the case when it was us were on top doing it to others.

It would be a good time to change our ways, to learn to build bridges to the others. It might also be a good time to learn minority survival methods.

Instead many are using their fear to justify hatred and acting worse than ever. That will guarantee that the pay back will be worse. The change in population political power is coming. It is a waste of time thinking that it can be stopped. Time to change direction and to adjust as needed. Giving up is never a good survival practice.

There are already white Americans who think whites are persecuted, and say so loudly. When whites become an American minority, I fear those voices will gain traction.

No doubt that they will. So it is up to us that understand to talk against that and do so loudly. Remember the problem with extremists is when ordinary and decent people do not respond because they are frightened. We have to do the very thing that we complain about every other people not doing. Thattoisa revolution.

I already speak out loudly against the Muslim Hatred and I can assure you that is not a popular position. But if I stay quiet,others might think no one is against it andgive in to play it safe.

I talk against racism of any kind. I talk against our police force and legal system that target minorities or the poor, or that lets the wealthy get off scot free most of the time.

Not that probably puts me on a few lists, government and other groups. So be it because if we are not every bit as loud as the extremists, who wins and who else will still be able to speak out on what they believe.

Freedom is what your demand for yourself and use.No one can give it to you, though others can take it away, unless you use it as much as possible.

I can be killed, I can be silenced, perhaps I even will be. But ideas can take on a life of their own. Even when buried and forgotten. Like forgotten landmines from a long ago war, they can suddenly explode back into existence when the time is right. So I throw out as many ideas as I can for the future. Others may take it and change it , but that is part of life as well,change.

I don’t agree with everything here. But I don’t need to, to know that getting ideas out is important. I also need new ideas to learn from, so I too have to hear and consider different ideas.

So we are the only solution that we have.Talk means nothing without action. We risk everything if we are going to change anythings. We have to be even more stubborn those that disagree with us, and that includes white extremists as well.

We cannot just tie ourselves to any one group that we happen to naturally belong to.

We are talking the whole human race and what nature will do if we do not change. Extinction.What we are trying to head off extinction, and and to make a life that is still worth living.

That means more than mere surviving. That means living, wanting to continue and becoming who we really are, not merely being part of the big machine, not just living in order to work, nor to be part of somebody else’s game plan.