[Alley Valkyrie is one of our talented monthly columnists. If you like her stories and want to support her work at The Wild Hunt, please consider donating to our fall fundraising campaign and sharing our IndieGoGo link. There are only 10 days left. It is your wonderful and dedicated support that makes it possible for Alley to be part of our writing team. Thank you so very much.]

I was headed toward a friend’s place for tea, on foot from my place to hers. I wove through Old Town, and then into the heart of downtown, climbing uphill toward the south and west. I followed I-405 as it snaked through the city center and up into the hills.

I first spotted her building from a few blocks away, perched near the base of a hill overlooking the interstate. As I walked across the overpass toward the building, I noticed how the road around the building winded back, seemingly defensively, as though it was holding the building and the hills behind it back from the man-made chasm below. I looked down at the highway for a moment and then back at the building again. The configuration of the streets around and the exits onto the highway were telling; the assortment of dead-ends and winding curves were suggestive of the historic layout of the area prior to the building of the interstate.

When I got to the other side of the overpass, I looked back for a minute, amazed at how what in actuality was the exact length of one city block felt like a much longer distance just then. It was as though I had just crossed over an invisible boundary, a ley line that felt as defensive as the curve of the road had suggested. The building itself, while obviously rooted, seemed to be almost holding on for dear life.

“Do you know how old the building is?“ I asked my friend as she let me in. “Does it pre-date the highway?”

“The building was built in ‘52,” she replied. “I’m not sure about the highway.”

I nodded. I was pretty sure the highway was built in the ‘60s, and the age and curvature of the street that snaked up past the building struck me as older than either the building or the highway. I made a mental note to do some research when I got home.

We had a lovely afternoon over tea and, after I left, I once again distinctly noticed what seemed to be an exaggerated distance and an energetic shift while walking back over the highway. Curious, I decided to follow the 405 again back toward home, but this time paying close attention to the specifics of the twists and turns; the blocks that were taken out; the houses that were obviously and sometimes awkwardly spared; the random dead-end streets that once cut through where the highway now runs.

![Older houses on an awkward dead-end street overlooking I-405 [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/IMG_2878-500x333.jpg)

Older houses on an awkward dead-end street overlooking I-405 [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

But while those stories are forgotten, the present negative effects of the highway have been a source of local frustration since the highway first opened. An unforgiving scar cutting through the natural topography, the highway is universally recognized as a visual eyesore, a pollution nightmare and a cumbersome structural boundary that awkwardly splits the western half of the city in two. The idea of a freeway cap has been floated around a few times over the years, but as it stands the 405 is a canyon of traffic and white noise, harshly cutting through the body that is downtown while seemingly creating a vortex-like boundary at its various crossings.

As I followed the 405 north past Burnside, I briefly paused and turned down at a familiar spot – the intersection where the highway rises from the ground and starts to elevate. While the elevated highway creates an unwelcoming, imposing shadow, the underpass provides a rare source of shelter to dozens of homeless folks who have nowhere else in the vicinity to stay dry. I walked under to say hello, and to my disgust I found that it had been recently swept by police, most likely that very morning.

I-405 underpass, swept by police. [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

* * *

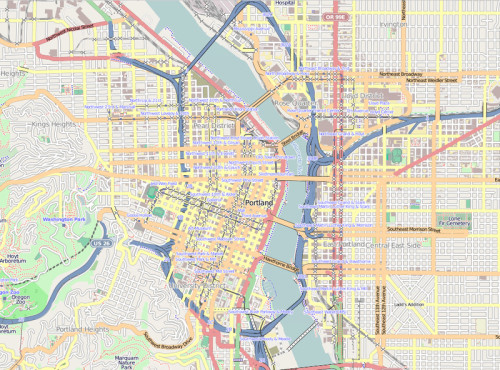

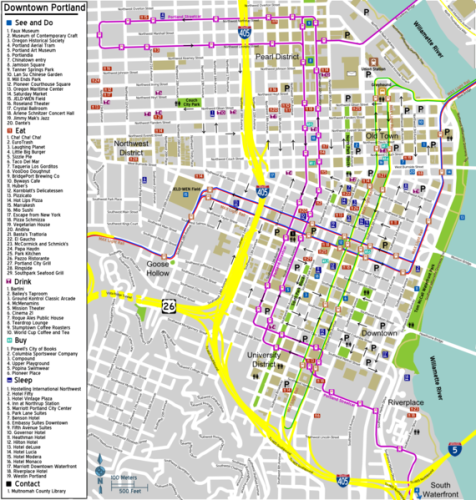

I-405 runs straight through the heart of downtown Portland. The highway branches off from I-5 just south of the city center, running below grade as it loops around and through the center of downtown, then rises in elevation and eventually over the Fremont Bridge, rejoining I-5 again on the east side of the Willamette River.

I-405 on the left and I-5 on the right in blue, forming a loop through and around Portland. [Image Credit: OpenStreetMap]

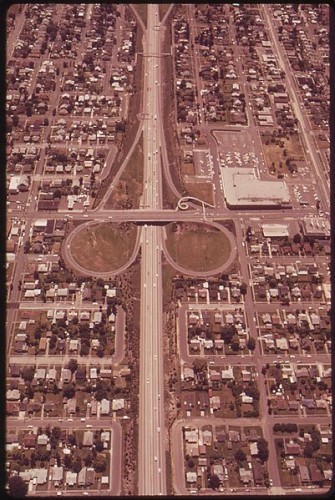

Aerial photo of Portland, circa 1955. The red dashes indicate where I-405 would be built a decade later.

A few days later, I found myself at the corner of NW Glisan and 13th on my way to the reuse store, subconsciously anticipating a ritualized pattern as I hesitated for a moment and summoned my strength before heading westward across the street.

Its not that far, I said to myself, and yet I felt myself resisting, as though I was trying to talk my body into a five-mile hike as opposed to a destination that was less than five blocks away.

Its not that far, I said again, and yet there was something about this last leg of the journey that was consistently overriding my everyday sense of time and distance. It wasn’t just a one-off; I felt this resistance every time I was set to walk west of 13th Street. I looked up at the terrain before me, the small hill that led to the overpass that crosses I-405. Its just a hill, I said to myself.

It has nothing to do with the hill, I said right back to myself, as I realized that this psychic resistance had a counterpart: the walk that I had taken over the same highway on my way to tea a few days prior. It was not the distance, nor the climbing elevation, but the act of walking over the 405 itself that felt so fatiguing.

I walked quickly up the hill and onto the overpass, pausing halfway across. Staring northward at the 405, I closed my eyes for a moment and envisioned the layout of Portland, transposing the route of the highway over that image in my mind. The slightly jagged line, running directly through the center of the natural shape of the land mass, immediately brought to mind an often bare-chested friend who bore a vertical scar down the center of his chest from open-heart surgery. I opened my eyes and chewed on the layers of meaning that sprung from such an image; the highways ripping through the hearts of communities, of neighborhoods, of the city center, the visual scar that the highway leaves on the landscape to remind us of that brutal surgery many years ago.

![The overpass and the highway beneath [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/IMG_2879-500x333.jpg)

The overpass and the highway beneath [Photo Credit: A. Valkyrie]

Suddenly the west side of Portland was a living being before my eyes, highway-as-scar torn through her chest, with cars being fed to the highway from the roads-as-arteries that cradled out and enclosed the land mass from all directions. The two halves of the west side took the shape of lungs on either side of the highway, and she breathed in and out as the cars circulated in and out from the highway and the arterial roads from every direction.

The west side of Portland, divided by the 405 in yellow. [Public domain Image]

I looked down as the cars sped past below, never-ending, through the arteries, drowning everything out for blocks. Everything, that is, except for the energetic effects of the wound itself, which could not be drowned out no matter how loud the white noise.

* * *

The next day, I decided to walk the length of the 405 as far as I could toward the river, and then cross over and follow the edge of I-5 going north, reading the journey along the way as though it were a story.

Where I-405 breaks off to route through the heart of downtown, I-5 runs over the Marquam Bridge and then north through southeast Portland. There, for the first few miles, it runs mostly on and over landfill, towering over patches of grass and fill dirt that extended the river’s edge by the equivalent of up to two city blocks.

It’s not until I-5 crosses Sullivan’s Gulch, just south of where the two highways rejoin on Portland’s east side, that I-5 creates an even more damaging effect than I-405 does through downtown. This time, the highway cuts through five miles’ worth of residential neighborhoods in north Portland up through to the Columbia River. The interstate cuts like a knife straight through a series of communities that were the heart of the Black community in the 1960s – a community that was already once-displaced a generation earlier as a result of deliberate racism and negligence.

Out of all the advances in urban planning over the past half-century, in not only technology and philosophy but policy and practice, the one true reliable constant is that eminent domain will inevitably be wielded against those who are the least equipped to fight it. Tucked within the overall story of any urban planning “achievement” is the suffering of those who were uprooted; their communities demolished; their homes taken for far lesser value than they were actually worth.

I-5 at N. Lombard Street, circa 1973. [Public domain Photo]

Walking along, taking in the details, absorbing the quaintness and the beauty alongside the construction and destruction, I started to alternate back and forth over each overpass I came across. The strength of its boundary felt even stronger here than it did several miles south on the 405, and with good reason. While the 5 in north Portland does not cut as deep as the south end of the 405 does, the 5, at the overpasses I was crossing, spans three city blocks as opposed to the single block-wide chasm that contains the 405 through the downtown core.

Each time I looked across at the houses on one side and then the other, I couldn’t stop thinking that what I knew were once pieces of a connected community seemed all too far away from the pieces on the other side. I thought again of the heart and knew I was standing in a place where the heart had truly been torn out, where two halves were permanently disconnected with little hope of reunification. I tried to picture the houses that once stood in the path of the interstate, tried to imagine what the neighborhood would have looked like without a giant canyon of speed and noise running through it, but contemplating the vastness of what had been obliterated quickly overwhelmed me. I thought of the heart and the arteries again, realized that I had fully taken in what I had set out to know for now, and I headed away from the interstate back down towards the river to process it all.

* * *

In the few weeks since I walked alongside the highways, I’ve gradually changed my routes so that I deliberately cross over the 405 on a near-daily basis. Each time I cross, I note the wound and the boundary. I greet the older buildings teetering at the edges, and yet I mainly focus on the warped perception of distance, often imagining that I’m pulling the two halves of the neighborhood closer together as I make my way across the chasm of traffic below.

And, while I can’t definitively attribute it to either a deepening of my relationship with the chasm itself or the effects of a deeper awareness and attention to specifics along my route, each time I cross with attention and intention I take away with me a little piece of understanding – a sign of some type, a detail that holds a greater meaning. Despite the eyesore despite the vortex, the arteries and the wall of sound, I’m finding that the chasm itself tells many stories from its edges.

It’s a fitting conclusion when I consider that the ‘story’ that originally focused my attention on the interstate in the first place was a building perched at the edge of the chasm as though it was holding on for dear life.

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Fascinating work, much to ponder in this essay. You might find interesting the use to which I-405 is put by the authoritarian Portland Protective Association in S. M. Stirling’s Enderverse series. (Which is pretty Pagan, btw.)

Thanks, Alley. As someone who frequently travels to LA and drives The Ten, I’m contemplating what magic I can regularly do on those roads . . . .

More good psychogeographical writing from you! I’ve long been fascinated by how the feral often blooms along these wounds, in the shadows of the freeways, under the underpasses, along the rails, by the abandoned piers….

I’ve often had similar thoughts, particularly while walking in urban areas, about how much more energy it takes to cross the “chasms” of large highways. Communities separated by highways are also changed in other ways and it is all done to accommodate the automobile. Older cities had buildings right to the sidewalks whilst new areas have large parking in front. Older cities had densely built dwellings whilst new areas have condos and apartment towers that have large expanses in between them. Everything is built for cars and requires cars to overcome the larger and more hostile boundaries to walking.

I thought that your observations of how the former city streets followed the landscape, and the image of the highway wound were really interesting. It is even more interesting to note how the grid-pattern of older city streets is in itself imposed on the landscape, and pre-urbanisation, the transportation artery of that area was the river.