[Alley Valkyrie is one of our talented monthly columnists. If you like her stories and want to support her work at The Wild Hunt, please consider donating to our fall fundraising campaign and sharing our IndieGoGo link. It is your wonderful and dedicated support that makes it possible for Alley to be part of our writing team. Thank you very much.]

“The housing crisis doesn’t exist because the system isn’t working. It exists because that’s the way the system works.” – Herbert Marcuse

Borders and Fortifications

On one side of the post office sits Bud Clark Commons, a Housing First complex that also functions as a day center and a drop-in shelter for the homeless. Extending just eastward from Bud Clark Commons are both Union Station and the Greyhound station, anchoring one of the defining corridors of what little still remains of Portland’s ‘Skid Row’.

Portland’s main post office. Photo by Alley Valkyrie

On the other side of the post office is the eastern edge of what is now known as the Pearl District, a neighborhood currently at the tail end of a twenty-year redevelopment plan that transformed the area from an industrial district to the most expensive neighborhood in Portland. Trendy shops, bars and restaurants and million-dollar condos now dominate the ten-block radius just west of the Post Office complex; a neighborhood which thirty years earlier was dominated by auto repair shops, warehouse art spaces, and various types of industry.

The post office itself is not only the city’s main post office, but also the main processing facility for all of Oregon and southwest Washington. The complex stretches from Hoyt Street to the tail end of the Broadway Bridge, spanning 14 acres and the equivalent of eight city blocks. The post office predates both Bud Clark Commons and the Pearl District by a generation, having first opened to the public at the height of the Kennedy administration.

Rear view of the post office complex. Photo by Alley Valkyrie.

While the physical presence of the post office creates a delineating barrier of sorts in terms of its sheer size alone, there’s more to it than just that. It serves as a significant energetic buffer between two neighborhoods that are on the opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum. The post office stands as neutral ground, holding a space understood as commons at an otherwise volatile crossroads where affluent folks often feel uncomfortable two blocks to the east, while poor folks are made to feel uncomfortable only two blocks to the west.

It feels and acts as a fortification as well as a territory of safe passage. But the fortification is seen as an obstacle in the present day, as the eight blocks that the complex rests on is among the most valuable land in Portland. City planners and local developers have been itching to redevelop the land for years and, after many years of negotiations, the plan is finally coming to fruition. The timeline has not been set as of yet, but the complex’s days are all but numbered.

I actually learned this news as I was standing in front of the post office itself, staring into the newspaper box at the headline. Since I don’t believe in coincidence, I stood there digesting the moment when a older man tapped me on the shoulder – a man who I knew to frequent the area around the train station.

“You live here, right?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied. He continued.

“You know this whole place is done for, right?” he said, gesturing with his hand in an arc towards the complex. “According to the news, its going to be condos or some crap like that. The whole thing, coming down.”

I nodded.

“I don’t know what they’re thinking. I mean, I know what they’re thinking, they’re thinking money. And it may make dollars but it makes no damn sense. Not to me, anyway. They want to take over all of it.” He pointed over towards the Greyhound Station. “All the hotels, all the SROs, straight up to Burnside, they want to take over all of it.”

“Yes, yes they do”, I said to him sadly.

“And where do we go then, huh? Where we all gonna go?”

He walked away without waiting for an answer, which was a small relief only in that I sure didn’t have one. The only thing I could focus on at the moment was that this was at least the third time that month that I had a nearly identical conversation in nearly this exact spot.

Vice, Temperance, and the Vanishing Commons

The term “skid row” originates from the greased skids that made up the roads that loggers would use to transport cut logs from the forest to the river in the Pacific Northwest. To be ‘on the skids” was to have no choice but to live in such an area, as the conditions of the roads were considered not to be fit for dignified habitation.

Portland’s skid row stretches down through Old Town Chinatown, butting up against the borders of downtown proper. It has unwaveringly held that territory since Portland’s early days when it was considered one of the world’s most dangerous port cities. The history of “vice” in Old Town is as old as the history of the city itself, and it is both that history of vice and the resistance against its proliferation that define much of the landscape and the historic nature of the area.

- Portland’s historic ‘Benson Bubblers’. originally installed as temperance fountains in the early 20th century.

As a result of well over a century’s worth of blue-collar domination, much of the original infrastructure is still intact. Old Town and the northern edge of Downtown are home to an impressive inventory of Victorian-era commercial buildings, many of which are historic landmarks and have been kept up to their original glory. Others, no less lacking in history, have fallen in disrepair over the course of many years, but many still retain landmark status and due to the current real estate boom are newly slated for renovation and preservation.

Unlike the sidewalks outside of busy establishments, which for the most part are regularly controlled and policed, the sidewalks outside the tenant-less, abandoned buildings of Old Town function as a commons, not too differently than the the block which contains the post office. In the absence of anywhere else to carry out such functions, homeless folk of all stripes eat, sleep, commune, fight, bicker, barter, hustle, and otherwise claim territory throughout these uncontrolled sidewalks, which in turn only adds to the desires of developers to gentrify the area and displace such folk.

Long abandoned, the Grove Hotel is slated for renovation and restoration in the near future.

Those who displace and renovate also rebrand, and Portland’s rebranding on a national level of being a haven and destination for craft beer is starkly reflected in the newer establishments that have accompanied the recent waves of gentrification throughout Old Town and the surrounding areas. Hipster vice has replaced working-class vice as the area is slowly overtaken by drinking establishments that cater to the young and affluent. Meanwhile, bars that cater to the neighborhood’s historic population have all but disappeared.

Business owners and community members alike credit themselves for “cleaning up” the area, and while I’m sure they’re “cleaning up” economically, it becomes apparent after a while to those who live here that they’ve simply replaced one group of unruly drunks with another. Apparently it was not the presence of “vice” itself that was supposedly “dragging down” the area as much as it was the socioeconomic class of those who were partaking.

Ruins and Reminders

Before Portland had a source and the proper infrastructure for importing natural gas, it manufactured gas from oil in a process known as “coking.” The Portland Gas and Coke (Gasco) plant was built in 1913 on the NW riverfront just across from St. John’s, just north of where the Cathedral Bridge would be built nearly twenty years later. The plant refined gas from 1913 until the city converted to natural gas in 1957, and the plant was shut down a year later. An estimated 30,000 cubic yards of coal tar had accumulated on the site over the years. Fifteen years later, it was covered with landfill when the site was sold, and most of the operational buildings were demolished.

The original administrative building, built in 1913, still stands and has been vacant for nearly sixty years. It is perhaps the most hauntingly beautiful Gothic ruin that I have ever seen with my own eyes. A ghostly reminder of the past, it is one of Portland’s most photographed structures, and over the past several years a fence has been installed and a guard put on duty in order to discourage explorers and adventure-seekers.

In addition to the crumbling condition of the building itself, the land that it sits on is among the most contaminated areas along a stretch of the Willamette River through Portland that has been designated a Superfund site. A DEQ report from the late ‘90s states that contaminated water was detected up to 100 feet below the surface of the west bank of the Willamette. Any significant cleanup of both the Gasco site and the Superfund site has yet to begin.

NWNatural, who still owns the building, announced last year that the building was to be slated for demolition. A community group attempted to raise the funds to buy the building, but they failed in their effort, and NWNatural announced last week that the Gasco building is to be demolished next month. Its reasoning mostly centers around safety. But what is unspoken yet completely understood is that, once the site is cleaned up, the land that the building currently stands on will be quite valuable.

It stands on its own as a sentimental tragedy that such a beautiful structure is to meet the wrecking ball, but there’s something that hits deeper in the timing of the announcement, given that demolition and gentrification have dominated both media headlines and local conversations nonstop for the past several months. The announcement comes in the same wave as the proposed redevelopment of the post office site, further talks of an “urban renewal” plan for the adjacent Old Town neighborhood, and a record number of demolitions and no-cause evictions. While the destruction of the building itself is a significant historical loss, the timing, the symbolism, and the layers of meaning and crossover between the demolition of the Gasco building and the greater overhauling of the city and its denizens — these combined factors speak to a much greater collective tragedy than the loss of any one structure.

Confessions over Coffee

“I mean, there’s a part of me that feels like I did a bad thing, but at that price I just couldn’t say no.”

I looked over at the table next to me and saw two men in suits with portfolio cases at their sides, having what obviously was a heart-to-heart over some sort of business decision. Intrigued, I leaned in slightly in order to properly overhear the conversation.

“Are you crazy?” the other man replied. “You said yourself that you profited nearly a hundred times what your grandfather originally paid for that land. Every other house on the block had already had a date with a wrecking ball. How many hundreds of houses have you bought and flipped over the past five years? This is really no different.”

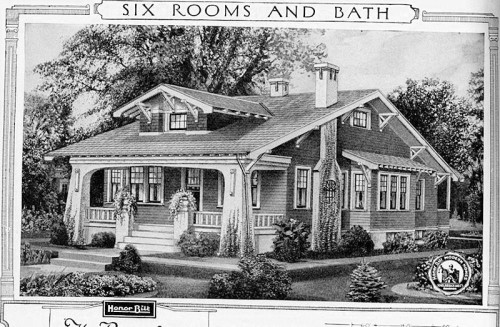

“It’s a little different. He built that house with his own two hands. That house was a Sears bungalow from the 20s… you know, the kind you bought and put together yourself. Three generations in that house. Mom’s still confused, still thinks we own the house or that she lives there, but we all agreed that she’s better off in a home… but still. It’s the house itself. Its this weird attachment, almost. Knowing they’re going to raze it. I feel like I signed its death warrant.”

1920s era Sears kit house. Public domain.

“Its business, Tom,” the other man said after a moment. “You need to remember its just business.”

“I know. I need to stop. It’s just a house. But there’s something that feels nagging.”

I stared at them in disbelief as I realized that this man, obviously a wealthy real-estate developer, had sold his family homestead out from under his ailing mother, not out of economic need but purely for profit. Suddenly I felt sick, and I quickly got up and headed toward the door.

That nagging something that you feel is most likely your ancestors, I muttered under my breath as I walked past them on my way out.

The Yelling Field and the Green Cross

Anywhere I’ve ever moved to, I quickly seek out the abandoned parts, the empty lots and the derelict warehouses. I look for a place, hopefully with features that echo, where I can yell as loud as I need to and nobody’s close enough to hear or investigate or call the police. I call these places my ‘yelling fields’.

When I settled into this neighborhood, I found my closest yelling field a mile or so up the main drag from my building, just north of the Fremont Bridge. A series of abandoned waterfront lots, a few dotted with ‘for sale’ signs but no sign of activity, and nothing else for blocks other than an ancient-looking bar and a run-down strip club a few blocks away across the street.

I thought it to be a consistent landscape that wouldn’t surprise me with any significant changes, but I walked by one day and noticed two things at once. My yelling field was suddenly fenced in, with a sign from a construction company posted in the center of the lot. And across the street, the strip club had closed, and in the window covering the old sign was a new sign that stated “Coming Soon” above a picture of a green cross, which in Portland is the universal symbol for a marijuana dispensary.

I stared at the sign for a minute, thinking back. Fifteen years ago, when I watched New York City undergo a similarly massive gentrification, the “Coming Soon” sign accompanied by a Starbucks logo became known as the telltale symbol that an area was about to gentrify. I realized at that moment that this symbol in front of me was operating on the same pattern, that the green cross held the same symbolic power in this new chapter of gentrification as the ubiquitous coffee goddess did when that first wave hit New York.

And sure enough, I watched over what seemed like only a few months as not only my yelling field, but several consecutive waterfront lots, went from abandoned industrial frontage to high-end condominiums and townhouse apartments. The dispensary opened right around the same time that the first completed development did.

I lost my yelling field while developers created a cash cow. Meanwhile, recent signage indicates that more riverfront construction is to come.

Demolition and Migration

I heard them talking while standing next to the food carts waiting for my lunch.

Food carts in downtown Portland. [Photo by Another Believer.]

Her friend nodded in acknowledgement, and she continued.

“Turns out that same developer bought three other houses on the same side of the street. Apparently if they’re approved for a zoning change, all four will be demolished to build condo units.”

“Yeah, that’s happening everywhere,” her friend said awkwardly, obviously not knowing what else to say.

“Yep, and so I’m just following the pattern of migration. I don’t know what else to do, so we’re all looking in way outer SE for a big house out there. But then the folks who already live out there are then pushed farther out once folks like me start moving in. So in following the pattern, I’m complicit in the cycle.”

They paused for a moment. “But my only other option is to go back to Arizona and there is absolutely nothing for me there. I have community here. I need to stay here. But I can’t stand the thought of being the gentrifier. I feel like I’m either I’m screwed or I’m screwing someone no matter what I do…”

I swear, this entire town is having the same conversation, I said to myself.

Remedies and Realities

I stepped out of Powell’s and saw a man with a sign.

“Rent Tripled, Newly Homeless. Need $28 for a Bed, Keeping My Job Depends On It.”

I gave him a dollar and walked down the street, looking up for a moment at a building just long enough to notice a green cross in the window. It didn’t matter where I went, what I read, where I looked, who I talked to. Everything, everywhere, from the people to the signs to the snippets floating through the air, a city in crisis that was broadcasting and reflecting its collective distress through every possible method of expression.

A few blocks later I walked past a man sheltering himself in newspapers. I stopped for a moment and noticed that the headlines that were covering his legs stated that Portland mayor Charlie Hales announced that he wants to declare a housing emergency, while the headlines covering his feet highlighted a proposed “demolition tax.” I’m not sure if the man was aware of the irony and symbolism contained in his presence at that moment, but the universal broadcast was suddenly much louder than I could really handle.

Walking home, mind racing, I realized that I couldn’t recall a day this month where the local headlines haven’t greeted me with displacement-related stories, whether its astronomical rents, multiple mass evictions of both tenants and artists, studies that stress that the national housing crisis is about to worsen, the impending eviction of a longtime homeless camp, ominous comparisons to the market situation in San Francisco, citizen calls for a renters’ state of emergency, and now the potential for a housing emergency actually being declared.

And yet the hope of a remedy provided no real or imagined comfort. It was clear from the level of the broadcasting crisis around me that most others weren’t fooled either.

* * *

bell hooks had it right when she described gentrification as “colonization, post-colonial style”.

Her words serve as an important reminder that the term ‘gentrification’ itself fools us into thinking that what is currently occurring in both Portland and in cities all over the world is a 21st century phenomenon and a “sign of the times.” In reality, this is only the latest round in a cycle of colonization and primitive accumulation that has been ongoing for hundreds of years. And, it is a cycle that will continue its destruction unchecked as long as laws, policies, and sentiments continue to value and prioritize profit and property rights over human need.

In the meantime, I remain in search of and in service to the ever-vanishing waterfront ruins and yelling fields, consistently and helplessly bearing witness as the economic powers allied with the green cross and the wrecking ball seek to displace and devour every last square inch of this city.

And in those searchings and wanderings, my mind keeps going back to the displaced. I keep thinking of the conversation with the man in front of the post office. I wish someone had an answer for him. I wish I knew where he could go.

I’m not sure where I’ll go, either.

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I have very strong feelings on this topic. I was born and raised in an affluent NYC suburb with a strong blue-collar streak. The son of a merchant sailor, grandson of a carpenter, great grandson of a postal worker, and great-great grandson of an Irish laborer. Nestled in wealthy Northern Westchester, this villiage served the big estates that surrounded it. We were the help, and when my old man was a kid every boy in town knew how to cuss you out in both Gaelic and Yiddish.

My town’s big problem came down to zoning. It was incorporated in the 1870s along the Harlem Rail Road, and every scrap of land was zoned residential. The idea was that the “city people” would build summer homes there along the train line. But they never came, and so my ancestors did. By 1985, the town was a nice mix of the affluent and the working class. White collar wokers taking the train to Grand Central every day, light industry nestled in the hills.

See, the city people never came, but too many parcels of undeveloped land remained zoned “residential”. When I was in high school, Toll Brothers started tearing down the swamps and geeenspace for new condo developments. Housing prices began to rise. NYC’s nuovo riche began moving in, buying German cars, and prattling on about having moved out to “the country”.

Then came 9/11 and the dam burst.

Today, I couldn’t afford to live where my parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents lived. Where my oldest paternal American ancestor placed an ad in the paper looking for work: “An Irishman, good with mules”.

And I’m the lucky one. I make good money, so for me its only a matter of mourning the loss of my heritage. A fantastic piece of affluent white privilege.

I think on those suburbanite shits I went to high school with, who are now gentrifying Brooklyn and Queens. I think of their arrogance, their privilege, their total fucking disconnect from reality. And then I think of the working class families they are displacing. I think of the house my wife grew up in in the North Bronx, and how there is no fucking way her grandparents would have been able to afford it today. And I wonder how in hell any working class New Yorker can afford to make ends meet anymore.

And then I wonder how long this can continue to go on.

Here in Salem, MA during much of the 90’s and early 2000’s we had a major condo craze going on with the full support of a mayor who was more interested in serving the needs of his frat brothers turned real estate developers than he was in doing what was best for Salem as a whole. There is a section of Salem known as “The Point” which contains dozens of WW2 era brick apartment houses. This was for decades “upper-low” and “lower-middle” income housing and just barely managed to maintain a “not yet a slum” status in spite of a proliferation of absentee landlords. It was a solid “working class” neighborhood with close knit, solid families.

At the height of the housing market and the height of the condo craze, building after building was being converted from (barely) affordable family apartments to high-end condos. The Point is close to downtown Salem and the Salem waterfront so if the gentrification was successful there were millions to be made. Two bedroom apartments that had been renting for $$800- $1,000/month were now “luxury condos” with an initial asking price of $450,000-$500,000. And families barely able to afford their rent were being “graciously” offered first shot at purchasing the same apartment they had been living in, in some cases, for 15 years or more at these ridiculous prices. Otherwise they had 90 days to move out.

But even more affluent, historic districts weren’t immune as the old Sea Captains’ mansions on Chestnut and Broad streets were bought up by developers only to be chopped up in the inside, transforming them from historic, single family homes into one and two bedroom condos. Prices in these neighborhood started at $750,000 for as little as 600 sqft of space.

For the most part Salem has always been a blue color, working class town. The Mayor and the city council during this period were determined to change that and transform Salem into a little more than a “bedroom community for” Boston. When long time resident complained about being priced out of their homes, the lack of concern from City government was deplorable.

Then the housing market crashed. The few condos in the point that had been sold for half a million dollars were now worth less than $200,000 and the ones that hadn’t yet sold were being reduced to less than $150,000 if not taken off the market altogether and rented out as apartments once more. To recoup some of their investment, the developers jacked the rents up to $1,500-$2,500/month and then submitted them as “Section 8” housing, meaning the majority of the rent is paid for with state housing supplements. This is good for low income families, but not so much for working families who don’t make enough to afford the rents, but make too much to qualify for assistance. So what are they to do?

My husband and I are lucky. We own a small house in a quiet neighborhood just a 10 minute walk from downtown. We are one of just 3 single family houses on our street (the rest are condos, apartments, and multi-families). And most rare of all, we actually have a small yard and off street parking that will fit two (small) cars if necessary during snow emergencies. But before we found our house, we had been pushed out of our own apartment after the building we lived in went condo with starting prices $150,000 above our max budget. So I feel for those who live with the fear of having their home sold out from underneath them because I’ve been there

Fortunately for Salem, we eventually got rid of that particular mayor and enough of the city council to pass new regs restricting condo conversions of existing apartments. Conversion of historic homes in designated historic districts have been strictly curtailed. For now, Salem has been more or less preserved as a working/middle class town. For now. Who knows what the future holds, though, or how long Salem will be able to fend off the next invasion of developers from Boston looking for new hipster stomping grounds?

It’s the same on the other side of MA too. They’re converting all the old mill buildings into high-priced condos and pushing the working class out. My husband grew up in the Berkshires and I moved there to be with him after college. We did well there for about 8 years, but then we both got laid off, and there were no jobs left comparable to what we were making before. We were living in a fairly cheap area, but having to get minimum wage jobs would not have paid our rent for our 1 bedroom apartment. After our unemployment ran out, we ended up moving back to my hometown in PA. And after 6 years here, we’re starting to struggle again.

I’d love to be able to return to my beloved mountains and forests, but I don’t see that ever happening without some massive economic changes, and since that won’t make any money for those at the top, I doubt we’ll ever see them. Those that still manage to keep afloat are so smug… just go to school, get a better job, work harder. And after you’ve done all that and still can’t get by? What then? When do we admit the system is rigged? And when do we do anything to change it?

We have the massively wealthy paying to keep the rules in their favor, all the while pinning the “have-little” against the “have-nots.” If those still getting by can convince themselves that the problems of the have-nots are all self-inflicted, then they can cushion themselves from the fact that it could so easily happen to them. For a little while… they’re all one callous corporate decision away from financial disaster, just like the rest of us.