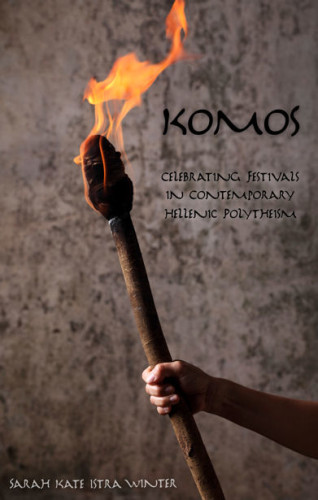

EUGENE, Or. — Last week, Sara Kate Istra Winter, also known as blogger Dver at A Forest Door, announced the release of her new book, Komos: Celebrating Festivals in Contemporary Hellenic Polytheism. It’s intended to be a “201-level” book for Hellenic polytheists who wish to explore the religion beyond household practice. As she was gearing up for publication, Winter was kind enough to answer some questions about her background and the book, giving a sense both of what Komos offers to worshipers of the Hellenic gods, and what it does not.

The Wild Hunt: For those who are unfamiliar, can you share a little bit about your religious practices and/or beliefs?

Sara Kate Istra Winter: I usually describe myself as being on the “outskirts” of Hellenic polytheism, simply because while I have a strong foundation in that religion, I am foremost a mystic and spiritworker and I let my experiences with the gods and spirits guide me to whatever will feed my practice best. Therefore I am also influenced by Slavic, Germanic and English folklore and customs, I pay some limited cultus to non-Hellenic deities such as Odin, and all of the spirits I work with are either local or personal, but not from the Hellenic tradition. I am devoted to Dionysos nearly to a point of henotheism (these days I might say I am more of a Dionysian than a broad Hellenic polytheist), though my relationship with Hermes balances that out a bit.

I am a hard polytheist, an animist, and I favor a foundation of reconstructionism tempered by ongoing personal experimentation. I have spent the past two decades studying ancient religion, including as part of a college degree, but I will ultimately choose to follow instructions from a deity or techniques confirmed by divination rather than a strict adherence to past practices.

TWH: What kind of experience do you have with Hellenic festivals specifically?

SW: I have been celebrating Hellenic festivals for nearly twenty years in one form or another. At first I mostly tried to fold them into my ritual group’s multi-tradition rites, then I experimented with a few on my own, then I spent about seven years closely working with Sannion (another Dionysian) to develop a complex and powerful festival calendar. These days I mostly do the strictly Hellenic festivals on my own again, and sometimes with the help of my Heathen partner. I have adapted ancient festivals, created many new ones, worked through interconnected festival cycles, and have experienced both large successes and utter failures. Some festivals were done once and never repeated because they just didn’t work. I have been celebrating others for many years consistently. I have accumulated a lot of experience via trial and error.

TWH: The word “festival” suggests something different than “ritual.” How do you define it?

SW: This is an important point that I address early on in the book. A festival is definitely more than a ritual (and in ancient Greece, it was also more than a sacrifice, which could be held separately from a festival). It is a set of rituals, and ancillary activities, that all focus on a common religious theme. That theme might be a certain aspect of a deity, or a seasonal marker, or a semi-magical concept such as purification. In addition to offerings, libations, [and] prayers . . . a festival also includes celebratory activities such as dancing, music, and feasting, as well as specialized rites particular to each one — this might be something like replacing a statue’s clothing, or making a certain type of cake, or going to a special place sacred to a deity. It is also important to note that a festival is by nature something that is repeated consistently, generally at the same time each year.

TWH: Where do you get your own ideas for festivals?

SW: Well I definitely started with research into the ancient festivals, which I still advise for others. Some of the festivals I still celebrate are ancient ones, such as the Anthesteria. But I also took a lot of inspiration from those and used it to craft new festivals, by learning what the basic approach was, what types of activities might work, what concepts could be expressed, etc. Some of my festivals spring from the place where I live — those honoring the local nymphs for instance, or marking times of regional significance (either culturally or environmentally). Others have arisen in response to personal spiritual experiences with my gods, wanting to mark those in some way, for instance to honor the specific faces of Dionysos that I myself have seen.

TWH: What might the solitary practitioner find valuable in Komos?

SW: Since I personally have done so many festivals either alone or with only one or two other people, and I’m pretty sure most other Hellenic polytheists are in a similar position, I wrote Komos from that perspective. Almost every suggestion is meant to be adaptable to a solitary practice. Frankly, the Hellenic festivals of antiquity were designed to be celebrated by large groups, so adapting those (or new festivals based on the same principles) for a large group now isn’t much of a challenge — the real issues come up when you try to figure out how to do the same things all by yourself. Processions, competitions, revels, these are all collective activities in our minds, and I’ve tried to suggest ways they can be incorporated even into a solo event.

TWH: How about someone who would like to organize something for a group, or in public? Does it include any advice about the issues that need navigating?

SW: I have mostly focused on solitaries and small groups with this book. I do not know of many people attempting to put on entire festivals (as opposed to rituals) for large or public groups. However, I do think the way I’ve broken down the key elements and the issues regarding timing and localization could all be applicable to larger festivals, and will be especially helpful when people are trying to create new festivals rather than just reviving the same few Athenian ones we all know.

TWH: You’ve described this as a “201-level” book. What would you recommend someone read or do before picking it up?

SW: Well, it would definitely be useful to read my first book on Hellenic polytheism, Kharis, which covers the religion in a broader sense. I also think anyone coming into Hellenic polytheism should at least read a few basic scholarly books to get a footing — though they don’t need to become scholars themselves by any means! — and this would include authors such as Walter Burkert, Martin Nilsson, Jane Ellen Harrison, Jennifer Larsen, Robert Parker, Karl Kerenyi, [and] Sarah Iles Johnston . . . I also like to recommend Pausanias since he paints a great picture of the variations in cultus across the Greek lands, and of course the ancient playwrights though you have to take them with a grain of salt.

However, I always stress that you can practice Hellenic polytheism from day one, and learn as you go from a combination of reading and experience. It doesn’t take an complicated knowledge to pour out a libation and hail the gods. The rest will come with practice. Komos will definitely make more sense if you’re at least familiar with the Greek gods and some basic ideas of how they were worshiped in antiquity, but it doesn’t require anything more than that. I define all the terms that are in Greek, and I take a fairly practical approach to the whole issue. I call it a “201-level” book because instead of just being an overview of the religion as a whole, it’s focusing in on a specific aspect in more depth, and aimed at people who want to really dig in and expand their practice.

TWH: Will this book be useful for people who worship Roman deities, or perceive them as identical to Hellenic ones except in name?

SW: I suppose it depends on how important it is to them to reconstruct the Roman way of doing things, which was similar but not identical to the Greek way. I admit I am not very knowledgeable about Roman religion, so I’m not sure exactly how much of this would be applicable. I have distilled the concepts that were especially important to the Greeks when thinking about what makes up a festival; I do not know how many were equally important to the Romans, although I would guess there is a lot of overlap. Certainly some of the specific ideas and suggestions could work for either.

TWH: More broadly, is this information specifically Hellenic in character, or do you include methodologies or strategies which could be adapted to unrelated religious practices?

SW: This book is definitely specifically Hellenic in focus. With all my religious practice, I attempt to explore what the foundational assumptions and priorities are in the original religion, and then extrapolate to create new practices that are still consistent with tradition. These things are going to be different for every culture, at least to some degree. Sometimes these differences are negligible — an athletic competition during a Hellenic holy day might seem quite familiar to a Norse heathen — but sometimes there are crucial differences, such as traditions in which you consume the offerings versus those (like ours) where that is forbidden. My discussion of the lunar calendar will have little relevance to those outside the Hellenic worldview, but my chapter on how to localize your rites might strike a chord with anyone practicing a recon-based tradition. I also briefly touch on the issue of celebrating festivals in multi-tradition households in my troubleshooting section.

Komos is now available through Createspace, and also on Amazon, along with Winter’s prior book on the subject, Kharis: Hellenic Polytheism Explored.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Oooh, something else to add to my To Read list. 🙂