“Incense to Burn” by Izzy Nguyen-Phuoc, (Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0)

Thin pale hands clutch a wand bound with a crystal and bundled herbs. The fingers of the practitioner are delicate, lithe, adorned with pewter and silver rings; a thing gossamer fringe from her sleeves or her dress drapes down, and she lights cones of incense in spaces prepared for them upon a painted-stone.

Magic seems to stream through the soft-lighting of the image, and we are left to wonder: Is she casting a spell? Invoking long-quiet spirits? Divining the threads of wyrd woven around a supplicant?

No.

She’s selling a product on behalf of a corporation.

The images that I’m referencing appear on the marketing blog for Free People, which offers ‘curated’ products for sale within ‘The Spirituality Shop.’ For those unfamiliar with Free People, it’s the parent company of Urban Outfitters, a company renowned for their well-documented theft and appropriation of First Nations and individual-crafter art, as well unabashedly selling overtly racist products such as Ghettopoly and “Navajo” liquor flasks..

For 68 dollars, you can purchase their ‘cosmic stick,’ or for 28 dollars you can either purchase an assorted bundle of driftwood sticks or a ‘hand-tied’ smudge stick. To a serious spirit-worker, witch, or wizard, such products are laughable, and they would likely agree with the cynic or the atheist who’d ridicule the use of spirituality to sell a product.

But that presents a problem. Spirit-workers, witches, and other practioners often do sell things, spiritual services (readings, curse-breaking, channeling) and products (wands, enchanted candles, herbal tinctures) through which others find their needs met. The logic of the cynic or the atheist, then, is of no use to the Pagan engaging in such transactions, yet we’d still take issue with The Spirituality Shop.

I’m tempted to say, “Welcome to the Capitalist appropriation of Paganism,” but I’d be misleading you here. It’s quite common, as Pagans are also consumers, and, anyway, we have a horrible habit of appropriating others beliefs and systems, compiling them and selling them back to each other as our own.

But still, it seems…wrong, somehow, for a corporation to present items roughly associated with our beliefs, dressed up in spiritual language, for profit. Many of us sell our services to each other as readers and crafters, and Pagan festivals very often have large markets of items for sale. How is what “The Spirituality Shop” is doing any different?

It’s tempting to fall back upon a particularly modern analysis. Free People is an impersonal corporation only out for profit, rather than a local seller, someone we know, someone ‘in the community.’ And while local trade is certainly something we should strive for, I currently live in a city where the largest on-line retailer of Pagan items (and pretty much every other sort of item), Amazon, resides. Corporations can be local, too.

Nor is it enough to say ‘corporations are bad.‘ As an anti-Capitalist who has worked in both small local-businesses and for corporations (as a cook, retail clerk, receptionist and a couple of professions I’d rather not talk about), I can vouch that working for Corporations was better every single time. They might rape the earth and exploit the poor, but at least their checks never bounce.

But there are several problems with The Spirituality Shop and other commercial outfits selling items with a sacred veneer, shrouded in mystical language and evoking the trappings of magic and the divine. The thing is, these problems are much larger than mere appropriation of an alternative religion and its activities and products. Rather, the problems are integral to Capitalism itself, or, rather, how Capitalism trains us to look at the world and everything in it as ‘objects,’ divorced from both spirit and social relationships.

To understand this, we need to look at the magical practices of Capitalism itself.

Commodification–or how nature becomes ‘things’

A commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties…. The form of wood, for instance, is altered, by making a table out of it. Yet, for all that, the table continues to be that common, every-day thing, wood. But, so soon as it steps forth as a commodity, it is changed into something transcendent.

Karl Marx, Capital

While many 18th and 19th century ‘Enlightenment’ writers were vociferous critics of religion and particularly those who made a living selling metaphysical objects and services to others (Voltaire was very scathing), one of them, Marx, specifically examined our relationship to products and services through a metaphysical lens.

Marx wrote extensively in alchemical terms about the way Capital and Labor crystallize into ‘value,’ much like chemicals and minerals ‘crystallize’ out of air or other materials in an alchemical apparatus.This value is an apparently magical property, added into the material realm through human activities (labor, mostly).

When a raw material like wool is still upon a sheep, it has no social value. This isn’t to say it isn’t valuable to the sheep, of course, but it has not yet entered into the abstraction of human social exchange except as a ‘potential’ to be used later. The process of shearing it from the sheep adds an extra social dimension to the wool as a ‘raw material,’ an object, a ‘thing.’

Now, human labor can be applied to that wool to turn it into other things, each further away from the sheep it came from. Carding, spinning and then weaving or knitting each add another layer of objective difference and distance from its original existence as a fuzzy covering on the skin of a sheep. Each of these abstractions adds ‘value’ (specifically, ‘use-value’) to the wool, which is why raw wool costs less than a woolen cloak.

If at any point along the way the wool is given to someone else in exchange for another thing (usually, money), it becomes a commodity, or an object of exchange between humans. This exchange transforms the item into something now alienated from all the other humans who worked it.

That alienation is essential to understanding pretty much everything about Capitalist society.

By removing any thing from the relations that formed it, the threads of community and meaning are severed in the very same way that a human traded as a ‘thing’ from Africa to the Americas was alienated from the world that she came from (and the communities and land which co-created her) and was now considered a commodity despite her very real existence as a human.

That is, in order to alienate or commodify someone or something, they must be made into objects, devoid of meaning.

Commodity Fetishism–the ‘religion of things’

Commodification occurs when an item is divorced from the social relation that produced it.

Turning something into a commodity strips it from relationship and meaning in order to be bought and sold. And there’s a second transformation, just as insidious, which occurs to the commodity. Its social value no longer matters to the seller or buyer, but a different sort of ‘value’ does–exchange-value.

The question is no longer ‘How much does this person mean to their family? or How useful is this table?’ but rather “How much can I earn from this slave? Or how much can I sell this antique for?

And on the other side, the buyers now ask themselves, “Is this a fair price for a kitchen table?’ or, horrifically, “How many slaves can I afford to buy?”

Those questions comprise “exchange-value,’ and there are several new social interactions creating that value. This is where “markets’ come in: the desire of a merchant to profit as highly as possible from an item and the desire of a buyer to pay as little as possible for it. “Supply and demand” comes into play, mostly on the seller’s side, because if there are a hundred people selling coats and only one person buying, each seller is limited on the profit they can make.

It’s in the best interest of a seller to create artificial scarcity, and we should note that many modern famines in Africa and India have actually been a result of sellers purposefully limiting their stock, rather than natural causes (see Raj Patel, Stuffed and Starved, among others).

All these relationships are again divorced or alienated from the humans who created the items, except in the cases of individual crafters directly selling their crafts. Walmart is full of alienated objects. A Saturday market? Not as much.

From a tree which has value-in-itself to a table bought at a furniture store is a long chain of humans who have worked the wood in some way or another. But, in most cases, you can no longer meet them. In fact, not being able to meet the communities of people who created an item is how companies like Apple are able to sell you phones made by people in horrific conditions — You’ll never meet them; you’ll never see their misery. So you’re decision to buy a smartphone is cleansed of questions of morality and ethics.

There’s something uncomfortable about buying alienated products though. Consider the difference between a meal cooked by your family and a meal purchased at a fast-food restaurant. It’s unlikely you know the minimum-wage worker who assembled your meal in her grease-smeared uniform. You have no relationship with her and, more than likely, she’s not considered part of your community. The communal and social relations of a meal are stripped-out of a drive-through burger or a factory-processed microwave ‘dinner.’ Not only are we alienated from the people who created it, we are alienated from the meal itself.

But we (or, many of us, I guess) eat such things anyway–and pay money to do so–despite that alienation. Those items have ‘value’ (because we pay for them and consume them), but that value is a sort of chicanery. The thing-itself has value again, or at least we believe it to have value inherent in the thing itself.

How much is a coat ‘worth?” An iPhone? A house? We assign a number to that item; a number of dollars or pounds or pesos, abstracting the thing one final time before it’s finally in our possession. That final abstraction is translated into the ultimate fetishized commodity, money, a thing completely worthless except for the potential it signifies.

Marketing Enchantment

When a thing is severed from the community who created it (humans and non-humans), it loses its ‘meaning’ (that is, socially-constructed value) and is an abstract ‘thing’ alienated from the world. In order for it to have meaning again, another magical process must occur. We usually call this ‘advertising.’

I’m loathe to admit this, but there’s some incredible Bardic magic in Capitalism. The fact that every reader of this essay can immediately conjure in their head what the Coca Cola logo looks like is a pure act of sorcery. Delve a little deeper and you can also likely evoke the taste of the stuff and might find yourself getting a bit thirsty, even if you make a practice not to drink it.

This is created meaning attached to an alienated object. It’s unlikely you’ve met many of the people who work in the factories where it’s created, and even its actual contents are hidden from public knowledge. What it’s even made of is a mystery.

Bards and witches can incite desire, fear, and bodily reactions in others, and enchanters can imbue material objects with abilities foreign to the item itself; so, too, does the advertiser.

In fact, someone must imbue commodities with new social meaning, otherwise Capitalism cannot exist.

The alienation of an object from the social relations that created it–and the horrific state of those conditions–are both unbearable to the mind. Alienation from production allows us to ignore slave labor and oppressive working conditions that create the food we eat, and those ignored realities are replaced with pastoral scenes of rolling fields and smiling farmers. Over enough time we stop questioning, but only as long as the charade is kept up and no one challenges us to think too much about who makes these things.

Therefore we don’t empathize with the poorly-paid workers who pick our coffee beans or sew our t-shirts. Instead, at most, we interact with the barista who pours are drink or the salesperson who rings up our purchase. We don’t empathize with the workers because they’re obscured from us, both by alienation and by advertising. This is also how we ignore the destruction of the earth by Capitalism–we don’t see it.

In fact, a lot of advertizement now involves invoking feelings of community, of naturalism particularly to help ease the pain of that alienation from each other and the earth caused by Capitalism. Worse, Capitalist ventures directly harming the earth have become ‘greenwashed.’ BP (once called British Petroleum) uses a green sun-flower for a logo, and automobiles with higher gas efficiency are referred to as ‘green’ or ‘environmentally friendly,’ as if those cars were going around planting trees.

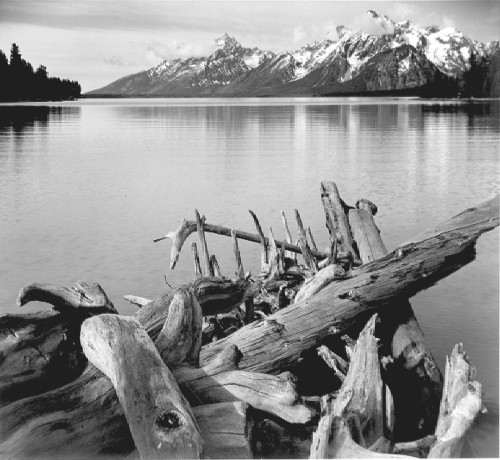

Driftwood photo by Ansel Adams (Public Domain)

Belief as a Product

Let’s return now to The Spirituality Shop.

Besides the sheer audacity of selling pieces of driftwood (freely found at almost any body of water), the fine folks who will sell you racist board games are engaging in the same alienation and commodification of objects as any other Capitalist merchant. But for Pagans, the aesthetic they employ should give us serious pause.

The language and photography in the advertising blog for The Spirituality Shop invokes precisely the connection to more ancient, non-Capitalist forms that many of us cherish about Pagan belief and practice. A connection to trees, to stones, to things like driftwood and the moon are all vital aspects of the Animist, Naturalist, and Pantheist religions within modern Paganism, particularly in our efforts to re-connect with the earth and its inhabitants–including other humans.

That is, Paganism is, if anything, anti-thetical to Alienation and Commodification. The moment a part of the Natural world becomes a mere ‘thing’ or an ‘object,’ its spirit, its being, its inherent worth and magic is ignored or even profaned. Alienation from forests is what allow us to cut them down callously, alienation from others is what allows us to make them slaves or sexual objects.

And it’s the sorcery used to help maintain that alienation which we, as witches, druids, spirit-workers, mages and priests must learn to fight.

When something becomes a commodity, it is stripped of its meaning, its spirit. We must fight off cynical uses of our beliefs to sell products, both from outside Paganism and from within. Value and worth are social creations, formed through social relationships, and nothing destroys social relationships like alienation.

Capitalism thrives on both greed and gluttony, excesses which destroy small communities but are difficult to redress in large ones. Alienation between the producer and the buyer is easier to create when our commerce isn’t personal and embodied; when you don’t meet the person who made your food or the person who’ll eat it.

And most of all, we should be wary of go-betweens, the enterprising sorts who offer to help us make money from our spiritual activities. It’s precisely at that point which alienation occurs, when driftwood collected on a beach becomes an ‘object,’ and the belief which creates a wand becomes a mere marketing ploy.

Relationship–or how sticks become wands

“Value” is a form of meaning that we attach to an item according to social relationships to it, whether those be use-value or exchange-value. But both of those meanings derive from relationship, both to the thing itself and to the beings involved in creating it.

Most magic is also relational. A spirit-worker, a channeler, a priest, a druid, and a witch all cultivate relationships with other beings (be they plants, rocks, spirits, or gods). To create a wand as a druid, for instance, I did not buy a stick from The Spirituality Shop or Amazon.com; I cultivated a relationship with trees (Alder, specifically) as well as gods and spirits related to Alder.

This isn’t to say I couldn’t have bought a wand, or had one created for me. In fact, my altar was created by someone else and gifted to me. I did not craft it, nor did I ever meet the people who’d cut down the trees to turn it into wood, nor those who made it into a bench. But the relationship of the person who made it an altar before I was given it remains; if anything, it’s her skill and her relationship to the god she made it for which imbued it with a rather profound magic in itself.

And here we have the final problem with The Spirituality Shop. We have no relationship with the creators of those items, nor likely did those creators have much relationship with the natural world. Only through the magic of advertising, the evocative chicanery and glamor of their imagery, might we imagine some ‘value’ in those items past their cost.

Thus, too, the problematic nature of even some Pagan ‘products’ such as Sabbat Box. We should be wary of attempts to sell us items evoking ‘Pagan Community’ and the imagery of magic, because this is the same ploy used to sell items devoid of meaning.

Magic might have a price, but relationship cannot be bought or sold. It’s the older truth behind the alienation between people and objects, the reason so many non-Capitalist peoples were communal and non-destructive to the environment in which they lived. Their connection to Nature and each other was relationship, which is the truest magic of all.

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

This is a great description, and yes Paganism started out as a Market Religion, where we are still financing our actions through mercantilism. It is what we do, and always have. Look at Pagan Pride which is merchant supported, or any number of events which have merchants. We do not donate as a whole we sell, to support our faith. Few do donate and give, but you are more likely to see a sale, auction etc, then a full donation box. So when corporations do it, they are following our own example.

Well the conclusion we don’t sell relationships is the only false note. We are a commodity creator, from soaps and incense, to spells, to wands. We do it all the time, and even our most dedicated leaders do it, daily. So that part is not true in the article, we are big on making magic into commodities. Just look at any festival, gathering, or other event, and count how many merchants selling relationships there are.

That’s sort of the point. They see what we’re doing, the level of success, and jump right into it. The problem is that they aren’t looking at the whole picture; they only see the monetary profit. They don’t see the relationships, the spiritual energy, the religious/spiritual aspects, the community bonding and strengthening, etc.

They lock onto what is sold, go about the least expensive means of acquiring/manufacturing it, completely skip the spiritual/energetic (magickal) step, but then market and sell the products as though they were the same stuff. They then undersell, making it difficult for the authentic merchants/crafters to stay in business and uninformed consumers, unable to find comparisons, fail to see the truth.

This isn’t entirely new and there are many stores, schools, and services in the Pagan community who have lost much of the spiritual purpose in favor of profits. Seeing major corporations doing it, though, not only paints a bleak future for what those who want Paganism mainstreamed will actually get, but also reminds us of the kind of negative energy that will be attached to products practitioners will be using (keeping in mind not all practitioners begin with skills to detect and cleanse such things).

A small historical quibble only, Ed, but at least on the West Coast there had grown up a sort of nature religion, touched with magic, that some even called Pagan, as early as the first half fo the 20th century, or even in the late 19th century. The whole idea of the citizen as consumer really took off only after WW2. So far as I can remember, the current form of Paganism slowly began to become a market religion in the USA only during the 1970s.

Yeah, check out those Pagan Pride merchants indeed. At least half of the merchants at the last Pagan Pride I went to were selling commercially-made crap from China that was undoubtedly made under slave-labor conditions, not anything they made with their own hands. That’s nothing to be proud of.

And no, corporations aren’t “following our own example”. You think they pay attention to us, you think they give a crap? Come on, that’s absurd. They aren’t following our example, they’re simply being capitalists. Many of the marketers behind this crap don’t even believe that magic exists.

The seductive power of corporatized spirituality seems particularly powerful for Pagans because I feel a lot of us have a yearning for more polish and professionalism in our communities. The corporate world can indeed create a slick package, but that doesn’t actually fill our need for great skill, gravity and quality in our communities.

While the sale of these items have always bothered me, either in the Pagan community or commercially, it does prove that Paganism is moving into the mainstream. Isn’t that what many of us have been fighting for? People are always going to find ways to make money from what is popular.

Maybe you’ve been fighting to move into the mainstream, but “many” of us have been fighting just as hard against that for years and years now and this ‘Free People’ mess demonstrates exactly why. Witches were never meant to be in the mainstream, both historically and currently. I’m so done with the respectability politics, with the need to be a part of the mainstream, and with the DELUSION that any of this has done us any good. From where I stand, its only hurt us worse, and personally I hope people take these turns of events as a sign to step back into the shadows where we belong.

I’m just curious about your take on how it’s hurt us worse, to become part of the mainstream, if you’re inclined to comment further.

I would direct you to two recent pieces, both by Jason Pitzl. One was his witchcraft manifesto, the other a essay on respectability politics that appeared last week. Both are easily findable on Google. Peter Grey’s essay “Rewilding Witchcraft” also sums up my feelings on it quite nicely.

I loved the Rewilding, and I’ll look for the others. Thank you.

Being mainstream isn’t my thing, but I recognize for others that may be considered being marginalized.

I’m sure that there were some who stayed in the shadows, but many ancient cultures held their spiritual leaders in the highest regard. These people were well known in their local communities and there was no need to hide. Therefore, I disagree with your concept of “DELUSION”. I would like to at least see Pagans to be treated as equals and not as lesser people. I don’t agree with hiding who I really am and “putting on a show”.

You don’t achieve ‘equality’ by submitting to respectability politics and the status quo. That’s more of ‘putting on a show’ than anything else.

This essay is a worthy follow up to the Pay to Pray story. For me, the main lesson is to think about how we individuals interact with our entire culture and economy. The U.S. at least is dominated by commercialism with a few tiny enclaves holding out. In my lifetime, I have seen dozens of services and products that used to be produced mostly in the household and exchanged among relatives turned into commodities advertised, bought and sold on the open market.

Although there is buying and selling within the Pagan community, it remains a place where almost everything you might need for your spiritual or religious practices can be home made, borrowed, gifted, or work traded for, books being an exception. Purchase for money is an option, not a requirement. For those who say that’s impossible where they live, I suggest that they are not actually part of a community. Religious minorities need to gather in physical proximity to their co-religionists in order to gain all the benefits of living in community.

Basically what happens and how commercialized we become depends on each of us.

So just look at the holidays in our nation and how much people complain about how they are so commercialized. Well, as long as we buy into how can we complain as we ourselves help keep it going?

Being both poor and suffering from being bi-polar this eat the holidays created a lot of stress. Stress I don’t handle well so I did the obvious thing I bailed out of the holidays and holiday spending. I do not take part in any of the official holidays. I do not buy anything for them, I do not take part in them, I do not decorate with holiday themed decoration, or take part in the appropriate drinking bing and I do not over eat.

See how simple that is. I feel no more holiday stress. I spend not a dime more on those days, so now I can occasionally go out and buy the books that I am interested in. Best of all I can put money aside, so if an unexpected expense shows up I don’t need to panic. How you sped your key or how you do’t sped your key ca e a apical act ad empower you as a person.

Same goes with my altar an ceremonial stuff. I do buy frankincense and I do buy bees wax candles. I can afford to cause most everything else I have either made myself, or were minor purchases over the years, or I have found and put to use. Again your choice is a magical act. So I am afraid it is unlikely this nice big corporation is ever never to make a dime off of me no mater how much they advertise.

So as I said it is our own hands whether we just become another mindless consumer. We really can take back control over our own life by deciding just how much we will buy into the consumer society.

We’re a pagan shop in Glastonbury, UK, and we try to be mindful of where things are coming from – we don’t sell Chinese-made plastic, for instance, and we do our best to source things ethically (so, we make our own wands, oils, incense etc). We do obviously try to make a living, but we concluded that there’s little point in selling mass-produced goods with dubious provenance.

My thinking on this has always been: You can buy the object, you can’t buy its spiritual power and significance.

You can buy a really nicely carved stick, but it’s not a wand until you’ve gone through some ceremonies or rituals that make it both spiritually charged and yours. Same for candles, incense, musical instruments, robes, athames, jewelry, divination tools, and all other commonly sold pagan goods. It’s not that selling those things is bad, just don’t claim to sell anything other than the object itself, and while you can advise your buyer it’s ultimately up to them to decide what they’re going to do with it.

Defining capitalism by what a big scary corporation does is a little like defining Christianity by what the Anglican Church does.

Nor are all corporations bad.

If you want quality anything, you’re going to have to look harder and not depend on the best price.

That being said, over time free market capitalism tends to give us better items in more variety at cheaper prices. Just look at these computers we’re typing these posts into. Compare them with the personal computers of a decade or two ago.

Sure, I can’t get heirloom tomatoes in the local grocery. But down the street there’s a nursery that will sell me the seeds and what I need to grow them.

I’ve got weird feet that are extra wide with no arches. Do you have any idea how hard it is to find shoes? But the important thing is that I can find them.

Don’t close down the pizza place because you don’t like anchovies.

Yes, it gives us better items in more variety at cheaper prices… at the cost of exploiting both people and natural resources. And yes, to a certain extent all corporations are bad in that they depend on extracting surplus value from either people or planet in order to create profit.

Please show me a plant or creature which does not exploit natural resources and other creatures.

Unlike those other creatures, you have the ability to decide if mutual trade would be beneficial or not.

I think we have very different ideas of what ‘exploitation’ means.

I have feet like yours. I can buy several good brands of day shoes, but finding dress shoes is close to impossible.

I go barefoot or sockfoot whenever I can.

Please, show me a corporation that does not exploit people or planet.

People have never needed “things” to be a worshipper of the Gods. Incense and wine is very nice when I can afford them (I only use real frankincense or myrrh). The ancient Hellenes knew that all you needed was an extra sharp kitchen knife for at home sacrifices. Standing, head held high, arms held up you prayed out loud because you were not ashamed.

I’m very grateful to Rhyd and TWH for starting this discussion.