Blackcoffeecoop.com

[The following is an expanded excerpt from a presentation I will be giving at the Polytheist Leadership Conference in Fishkill, New York on July 11, 2014]

I’m staring at a pile of shiny, polished rocks on a counter by the register. Some are smooth river-stones painted in iridescent colors, others are polished common gems, none particularly capturing my interest more than the small handwritten sign in front of them:

“Take a crystal, leave a crystal.”

Just a few minutes before, I’d stared at the wall above the urinal in the bathroom of this cafe, standing longer than was needed for the task at hand, reading and re-reading the poem displayed on the poster. The words admonished against despair, against giving in to the crushing weight of monotonous conformity, urging the reader to look for the presence and gifts and delight of the gods.

Perhaps it might seem strange to some that I wasn’t seeing this all in a Wiccan shop or Occult store. Perhaps where I found these things may seem even more strange: an Anarchist café in Seattle.

But this shouldn’t sound strange at all. Paganism and its beliefs mirror the struggle of Anarchists, and the indigenous activists who host ancestor prayers at that same cafe, and the queer trans* folk who hold meetings and organize protests against corporate pride events or the killing of a man who didn’t have correct fare on the light rail. The beliefs of Pagans, at least on the surface, might seem aligned to the so-called “eco-terrorists” who sabotage the industrial machinery which rapes the land and poisons our air and water, slaughtering thousands and thousands of species upon the earth in which we and the spirits dwell.

They are fighting against hegemonic control of existence, the limiting of human life itself; against the structures which displace people from the earth, disconnecting them from the strength and influence of spirits and ancestors, and turn humans into consumers and producers and subjects of hegemonic control of the powerful. And particularly, they are all fighting against the crushing oppression wrought upon the world by Capitalism.

We should be too, if our beliefs are more than mere opinion.

The Matter of Belief

One of the civic myths of late-capitalist Western democracies is that their citizenry is free to believe as they choose. Enshrined into many of the constitutions of European and European-derived democracies are laws guaranteeing the free-practice and free-conscience of each individual, and such laws are further re-iterated in supranational documents such as the UN Charter of Human Rights.

There have been relatively few government-sponsored mass-arrests of Heathens or Jainists in any European country, so on the surface, the guarantee of such rights seems to be true. While the recent experiences of some Pagans in isolated areas might certainly speak to a limited and merely localized persecution of gods-worshipers, it is incredibly difficult to make a legitimate case that America or any Western European country systematically persecutes those of minority religions.

As such, though, I’d argue that precisely the opposite is the case; that one is hardly free to believe what one wants in any of the Western democracies, and, worse, there is specifically a prohibition against certain sorts of beliefs. And most of all, that prohibition is precisely one of the most important bases of Western democracy.

The problem here, I think, is that we fail to understand the very physical nature of belief.

Belief is generally seen, in common parlance, to be an internal category, descriptive of an interiority invisible to any, except the person who experiences such certainties. As such, we tend to regard belief in the same category as “opinion,” a description of an inclination towards particular ontological positions but otherwise indefinable except through verbal communication.

I believe in multiple gods, and when I say “I believe in multiple gods,” I have thus communicated to you my interior state and theological position. But you, the hearer, must judge whether I have expressed something very deeply held, or merely a philosophical stance towards the subject. The ambiguity inherent in such a statement increases if you have no actual relationship with me. Conversely, if you also profess a similar belief, you may wish to parse out further precisely what I mean by “multiple” or “gods” (that is, am I a Polytheist with monist tendencies, or do I mean “literal” gods or more archetypal or psychological expression of deity?)

Expanding this difficulty out of the personal, though, one can see how such statements of belief might become even more ambiguous on the level of social groups, cultures, or entire nations. When we consider statements of statistical fact regarding the religious affiliations of entire nations, like “there are 828 million Hindus in India,” we accept such statements generally as equivalent to “828 million people in India profess to a belief in multiple gods.” But still, we know very little about what such belief actually means beyond the professions of faith and the self-identifications. We might be well-versed in the structures of the Hindu religions and thus have a greater sense of what is meant by “828 million Hindus,” but this still resides fully in the realm of interiority.

Hindu cave temple at Ellora [Photo Credit: Pratheeps/CC]

The same can be said of Christians, or of any other religious group which professes belief in divine beings who can be experienced, communicated with, oblated to, or interceded with through structures. That is, the landscape itself attests to the interior experiences of individual and group belief, revealing physical activity of the believers which results in the construction of very physical things.

It isn’t just the physical structures, however, which can be used to discern the content and depth of the belief professed by any individual. The physical activities of those whom believe in gods and spirits can also be observed. Christians who wake up early once a week to attend church services are engaging in actual religious activity on account of their beliefs, just as the Muslim who prays to the east five times daily does so on account of her belief in Allah and the prophet Mohammed.

Such activity can be observed not just by others who believe similar things, but even among those who profess no actual belief in gods or spirits. An anthropologist observing the activities of the people he studies can thusly attest to a whole range of activities (often categorized as specifically religious), which are signs of the meaning of interior experiences. That is, it’s precisely all these physical activities which tell the observer what is meant by those statements of belief, and we can then begin to formulate an understanding of their faith.

More so, it’s precisely those human activities which point to the existence of the gods and spirits with who humans encounter and worship. As the post-colonial historian Dipesh Chakrabarty says in Provincializing Europe:

“…gods and spirits are not dependent upon human beliefs for their own existence; what brings them to present are our practices.”

Faith Without Works…

I’ve taken a very long way around to get to a point which was made several thousand years ago by one of the minor writers of the Christian’s scriptures. That statement, and the meaning behind it, later became crucial to a split within the Catholic Church 1600 years later during the Protestant Reformation: “Faith without works is dead.”

We can interpret this statement in a more modern and Pagan standpoint by briefly mentioning many of the recent conflicts which led to several gods-worshipers being named “The Piety Posse” on account of their insistence that one should do things for the gods that one believes in. It’s surprising no-one reoriented the debate to the question of the physicality of belief. That is, if Belief means something, it results in physical activities stemming from those beliefs. Or, again, if you believe in gods and do not physically do things which belie such beliefs, your profession of faith is suspect.

Rather than re-invigorate that debate (or really, any others), we should expand upon that conflict to apply it to the rest of Pagan-aligned belief first, and then to that of Belief itself. As it is impossible to understand the interiority of any subject (which ultimately makes them an unknowable “Other”) without the physical manifestations of their beliefs, the polytheist “challenge” to mainstream Paganism is precisely that gods, if they actually exist, result in actually-existing actions on the part of those who experience and believe in them as actually-existing.

This stance, called “radical” by some, is similar to the same challenge posed by indigenous and anti-colonial resistance movements, queer political actions, and leftist challenges to mainstream political parties. Each pose the same critique to the dominant hegemonic political order, that it is not merely enough to have an opinion that another world is possible, but rather one must physically manifest such beliefs into the world.

From this viewpoint, then, we can begin to re-examine precisely what is meant by “freedom of belief” in Western Capitalist democracies. One is certainly “free” (by which one really means “not restricted from”) believing in anything one chooses, but any belief which affects the world around the believer falls into a completely different category. That is, if that belief isn’t mere opinion, than there are, indeed, a whole host of prohibitions against that belief.

One is free to hold any opinion one wishes. However, if that stance rises to the level of actual “belief,” and the person espousing such a belief then begins to do things which show that he or she actually believes such a thing, they quickly fall into the political category of “radical” or “fundamentalist,” and there are laws against acting out such beliefs. We can see such restrictions quite clearly in Europe, where advanced Capitalist democracies such as France and Denmark have outlawed such physical manifestations of belief in schools or passed laws against Kosher and Halal butchery. In America, we can see similar attempts to ban minority expressions of belief while simultaneously affirming the dominant religion’s right to physically follow through with their beliefs.

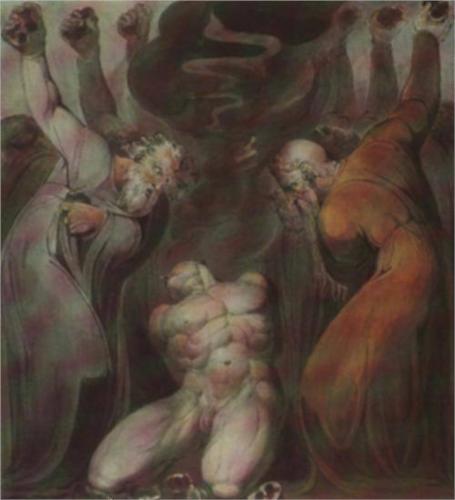

“The Blasphemer,” by William Blake [Public Domain Photo]

It would be facile merely to claim that the West is hypocritical. Hypocrisy requires a degree of self-awareness, a purposeful decision to act in a way contradictory to the manner one demands others act. It would not be merely facile to argue this–we’d be utterly wrong.

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek puts the problem succinctly in an oft-quoted anecdote:

In an old joke from the defunct German Democratic Republic, a German worker gets a job in Siberia. Aware of how all mail will be read by censors, he tells his friends:

“Let’s establish a code: if a letter you will get from me is written in ordinary blue ink, it is true; if it is written in red ink, it is false.”

After a month, his friends get the first letter written in blue ink:

“Everything is wonderful here: stores are full, food is abundant, apartments are large and properly heated, movie theatres show films from the west, there are many beautiful girls ready for an affair – the only thing unavailable is red ink.”

And is this not our situation till now? We have all the freedoms one wants – the only thing missing is the “red ink”: we feel free because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom.

This unfreedom can be explained precisely as our inability to manifest belief into the physical world while simultaneously existing under the ubiquitous delusion that we are relentlessly free to believe whatever we desire. In fact, that unfreedom might be adequately restated as a sort of ban on belief-which-matters, or belief which might physically challenge the power of hegemonic Capitalism.

Witches, Priests, Bards, and Rogues

An Anarchist, or any anti-Capitalist for that matter, believes that Capitalism and the structures which support it must be abolished. They are certainly free to have an opinion on that matter, but they are forbidden by all manner of laws from actually doing anything about it, thus ensuring that such an opinion lingers in the suspended opinion-stance and is never manifested in the world.

Fortunately, Anarchists don’t care much for the laws which prevent them, as it makes little sense to truly believe that a system is destroying the planet and causing human misery, and not try to do something about it.

But here, then, is where most Pagans appear to part ways with others who share many of their beliefs, and I’m not fully certain why this is. One of the many definitions of Paganism in currency lately is a “collection of earth-based spiritualities,” but the amount of Pagans still using petroleum suggests that perhaps Paganism merely holds a generally-favorable opinion of Nature, rather than believing it should continue to be around for awhile.

It isn’t enough merely to think things should change. And though my words function as a criticism of modern Paganism, I hope I’ve also shown how we’ve gotten ourselves into this restrained position. It’s us, but it’s also not just us. We are free to think what we want, but we are also quite unfree to act upon our deeply-held beliefs, forcing them to languish as mere opinion.

But the hegemonic power of Capitalism seems to be weakening again, and the fierce calls to awaken to belief-which-means-something are beginning to threaten the uneasy (and unholy) peace many of us have made with the powerful. Peter Grey’s recent essay “Rewilding Witchcraft” (and his cunning and cutting screed against belief-as-mere-opinion, Apocalyptic Witchcraft), is hardly the only such call within Paganism, and one might actually read the sudden apparent surge in new “polytheists” as a sign of the weakening of hegemonic control.

That is, it is almost as if the gods and spirits themselves are bursting through the walls we put up against belief, demanding that we do something.

The question is, though, will we Pagans see the allies all around, human and non-human, all pushing towards a new assault against the systems which oppress others and ourselves? Or will it be enough merely to “like” the earth and the old ways, with all the meaning and affect of a Facebook status update? Will we let our hopes, dreams, and desires languish in the dark, repressed interiors worlds, or might we have the courage to make manifest and make true our beliefs, regardless the threatened cost?

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

There’s a facile equation here between capitalism and ravishing the Earth. The old Soviet Union had a terrible environmental record.

Just because the USSR trashed the environment doesn’t mean that capitalism is any better. Indeed, we can easily see that capitalism *has* caused vast damage to ecosystems across the planet. The reduction of our environment to a mere commodity for exploitation is a serious issue that needs addressing.

It’s more accurate to say that capital rather than capitalism has despoiled the environment. In the USSR the state owned the capital and proceeded without even the mild environmentalist restraint the capitalist US puts on the process.

Depends on what you consider capital to be.

You do realise there are other alternatives to Capitalism besides Communism, yeah? Both mechanize society in the name of “Progress” and “Improvement,” and both are terrible. Capitalism seems to survive better entirely on its trick of convincing people that such cultural and environmental destruction is actually “freedom.”

Of course I’m aware of alternatives; I was in my twenties in the Sixties. But I’m also aware that anarchists didn’t used to be environmentalists, at least not heavily, until they woke up along with everyone else (well, not everyone) post-Rachel Carson. I recall one article back in the day to the effect of “Ecology is a Racist Shuck.”

Uh, Proudhon wrote in the 1800’s.

Also, George W. Bush was also in his 20’s during the sixties.

The Sixties was a time in which ideas that had been dormant, especially during the Fifties, burst forth again and demanded people’s attention — including economic, theological and sexual ideas.I didn’t run into Dubya then but I hear he was having a better time than I was, and paid for it.

We know that neither communism nor capitalism has worked for the Earth, let’s propose strategies for new ways of being in harmony with the Earth. Sun Bear predicted that those who live in small, sustainable communities will be the ones to survive the Cleansing Times (now called The Great Shift by some). If you can’t go on the land with a small community, perhaps you can get to know your neighbors, start sharing and bartering with the folks on the street. However, I think we have all gotten away from the author’s main point, that pagans are not necessarily doing much about ecological issues despite our professed love or liking of the Earth. This same assertion was made by Bron Taylor in his book Dark Green Religion. He thinks the surfing community engenders a greater potential for changing our ways of living on the earth than Pagans do! This bothered me, I didn’t like to think it might be true. Do we know what percentage of Pagans are making efforts to live in harmony with the earth? I would expect that more of us would than other demographics, but that could be a delusion on my part. Recently, our local Grove, Spiral Grove, sponsored a Greening Fair to help inspire the local community. We had terrible turnout despite good PR–not one local environmental org took advantage of the venue we offered for educating the community about their concerns. I imagine they did not want to be associated with a Pagan group. We had one Pagan who had a table against fracking. We had a permaculture teacher who I do not know his religion. And we had natural crafters, an interfaith prayer circle that no Christian clergy would join, and lots of eco info that we shared. I believe Pagans did make up the majority of the people who participated, but many more showed up when we used to sponsor our annual Witches’ Fair. In this context, I must give honor to Starhawk who travels around the country and the world, teaching permaculture.

I’ve always appreciated whomever it was who said that while Sino-Soviet Communism may not have been the correct answer, Marx was still asking the correct questions.

It is certainly true that anarchists are not free to dismantle capitalism no matter what they believe about it. But when it comes to beliefs that would be classified as Pagan and not anarchist (with the full understanding that for some, including yourself, there is considerable overlap), I would argue the primary impediment to manifesting those beliefs is not a lack of freedom but a lack of will.

Speaking of his Christianity, GK Chesterton said “it has not been tried and found wanting, it has been found hard and not tried.” I would argue that’s true of any religion worth a damn.

One of the primary – and most difficult – tasks of religious leaders is convincing our co-religionists that the benefits of a pious life are worth the effort, and doing so without the power of coercion. It’s hard enough to convince myself, day in and day out.

I love Chesterton, particularly Orthodoxy and the chapter, “The Politics of Elfland.” I used to define my politics as “Chestertonian Marxism.” Interestingly, the Slovenian philosopher I quoted, Slavoj Zizek, quotes Chesterton a lot.

I do address the problem of will a bit in my presentation, particularly as it regards “Divine Trauma,” or the moment when someone experiences the gods and spirits and must make a choice between embracing them or putting them into the category of “madness.” Telling people that you worship actually-existing gods as opposed to archetypes is an epic act of courage, because you risk being thought insane by your community. That is also an act of intense will, and I can see the many reasons why many people fear that act of will. And I’d argue that it’s quite similar to the moment that an Anarchist sees the widespread oppression of the system and decides to take action rather than keep silent.

The moment the anarchists become a real threat, capitalism will crush it like an eggshell.

An excellent illustration of my point–that it’s “safer” to have an opinion that things should change than to actually-believe they should. This is the hegemonic threat, identical in process to “the moment you act as if the gods are really-real, you will be called insane.”

Reading this, it occurs to me that there are probably any number of people who are misreading the argument laid out. One of my recent epiphanies in regard to Western politics (and especially American politics) is that there exists a deep misunderstanding of the use of the term “capitalism”. Due to decades of propaganda, there is a strong tendency to associate “capitalism” with “market systems”. Even when the difference is laid out (capitalism is a system in which those who are declared “owners” of capital goods are allowed to make decisions regarding those goods, and sometimes other objects, that have wide-reaching physical and political implications; an obvious example is the assumption that those who own logging equipment should have some measure of access to public lands to use those capital goods to harvest resources in the form of trees, but more subtle and even nefarious examples exist), people quickly return to an evident conflation of the two.

Meanwhile, there are any number of non-capitalist market systems, which have all of the economic benefits of the market-based distribution of resources without necessarily the drawbacks of “the tragedy of the commons” and similar failings of capitalism. (Those systems may have their own drawbacks, of course, and I am not advocating here for any specific attempt at a solution.)

This is quite true. I’ve noted, particularly, that when one says we should abolish Capitalism, a common response is, “but what’s wrong with buying and selling?” Also, when one talks about the history of Capitalism, quite often I hear, “but we’ve had money for thousands of years.”

In both cases, it’s particularly fascinating how Capitalism has so thoroughly re-inscribed itself into all social relations (Marx’s point) that we collectively have trouble historicizing it. This process is hegemonic, and we re-enforce it daily. What should be of particular interest to all magically-inclined folks, though, is that it seems to be the same process by which we enforce the “disenchantment” of the earth and collectively have trouble seeing the world of gods and spirits around us.

The separation of humanity from the land that capitalism and monotheism before it put forward, the inversion of humanity’s relationship of belonging to the land, has been one of the most insidious, vile, unholy, and destructive forms of belief-in-action.

The example you give of logging is problematic. Whilst logging equipment is capital, there is a common thought that natural resources are also capital.

The best example of this is using land as collateral for loans and the suchlike, and how that lands value can vary, depending on what resources are contained therein.

That’s fair, but I was specifically talking about the use of public lands by loggers in that example, not about land ownership (which is an entirely different problematic element). In the US, though I can’t speak to the practices in other countries, this is often allowed for token fees that in no way represent the loss to the public, but are mainly designed to keep those without wealth in capital amounts from benefiting.

I have very little doubt that the government (as controller of public land) benefits from the exploitation of resources reaped from public land.

If it does not, then, doubtless, individuals within government do. (Just how many members of government have vested interests in resource exploitation organisations, such as oil companies?)

I certainly can’t argue the fact that the administrators of the public trust in a capitalist system often do so for personal gain. In such a system, such administration easily becomes merely another form of control of capital.

Sadly people have really only been exposed to capitalism that has been largely unregulated. It’s basically a tool. All tools have safety rules and safety devices that keep them from harming the people that use them. If you remove those safety devices or ignore the rules, they hurt you. Unregulated capitalism is like a deadly chainsaw. But if the tool of capitalism is used properly, you get innovation, invention, ideas, growth, evolution and still can manage to not kill your planet, marginalize your people or end up with 1% of your population owning all the toys. We have never tried it though, in earnest. Read about “conscious capitalism.” There are many books out now.

I’ve heard this argument too many times to count. That is, what we need is not no-capitalism, but “greener” capitalism, or “free-er” or “less corporate” or even, my favorite Orwellian nightmare, “compassionate Capitalism.” The contortions that the wealthy will go through to continue justifying their position is fascinating; even more so, how quickly some are willing to “buy” into it.

The argument that Capitalism causes innovation has been thoroughly disproven. For a lucid take on this, I suggest David Graeber’s essay here: http://thebaffler.com/past/of_flying_cars

There are several reasons I see as to why Pagans don’t do more.

First, there are disagreements on what the definition of Paganism even is or should be. While I don’t really have a problem with the “earth-based religions” label so much, there are some individual Pagans who don’t even necessarily agree with that definition.

There are also individual points of view that tend to be polarizing, different ideas of how Pagans should behave. As an example, some might believe that Pagans should all be vegetarian or vegan if they really care about the environment, some might be spiritually empowered or at least not be bothered by the consumption of meat.

A more specific example was seen at Pantheacon one year. A group called Coru Cathubodua hosted a ritual that included the consumption of horse meat. Such a practice is quite traditional, and horse meat is still eaten in many countries. It is easy to understand why such a practice could be spiritually meaningful. Perhaps, since it is a traditional practice, it made some participants feel more connected to their ancestors or to tradition. It could have made some people feel more connected to horses by taking it in to become part of themselves. It could have made some people feel more connected to goddesses such as Macha who are associated with horses.

Though it may seem contradictory to our modern sensibilities, many historic feasts to certain deities included the meat of animals deemed sacred to them as a way of connecting to those deities. Some, however, were disturbed or outraged by it. To some, it was sacrilege or disrespectful to nature. Though you are probably talking more about political action or greater acts, that demonstrates the second issue, which is that Pagans often disagree on what Pagans should or should not be doing. Speaking of politics, there is even more political diversity in Paganism than some people realize.

A third issue deals with leadership. There have been some great Pagan leaders that have accomplished great things for the community, but I know that at least in my local geographic area, no one seems to want to step up and take a leadership role and really inspire or organize action. I’ve seen Pagan groups where great ideas have been discussed, and everyone agrees that it’s a good idea, but something gets lost beyond the “talking about it” stage. So there’s something lacking at least in some local-level leadership or in local groups concerning getting motivated, organizing action, and following through with it.

That’s what I’ve noticed anyway. People not stepping up and taking leadership roles, difficulty organizing, varying opinions on what Paganism is, and disagreement on what Pagans should be doing. Let’s face it, we’re a very diverse group of individuals, and as such, it’s difficult to rally around specifics when not everyone can agree on those specifics. To truly accomplish action within the Pagan community, you would have to find something that everyone from the most conservative, macho man, Odin-worshiping Reconstructionist hunter to the most left-leaning, hardcore feminist Dianic Wiccan vegan, and everyone in between or beyond could agree upon and rally behind. (No offense meant by the stereotypical caricatures, but those are the biggest opposites in the Pagan community I could think of off the top of my head to best illustrate the point.)

I think that’s what the difference is between Paganism and the other groups you mentioned. Other groups such as Anarchists tend to have a unifying factor or a lot more in common. Though there seems to be a little tension sometimes between some sub-groups of the LGBTQ community, from what I’ve seen they still also seem to have a lot more in common with each other than random Pagans generally do.

“That’s what I’ve noticed anyway. People not stepping up and taking leadership roles, difficulty organizing, varying opinions on what Paganism is, and disagreement on what Pagans should be doing. Let’s face it, we’re a very diverse group of individuals, and as such, it’s difficult to rally around specifics when not everyone can agree on those specifics. To truly accomplish action within the Pagan community, you would have to find something that everyone from the most conservative, macho man, Odin-worshiping Reconstructionist hunter to the most left-leaning, hardcore feminist Dianic Wiccan vegan, and everyone in between or beyond could agree upon and rally behind. (No offense meant by the stereotypical caricatures, but those are the biggest opposites in the Pagan community I could think of off the top of my head to best illustrate the point.)”

This is where I say that if you want to move the Pagan community in a direction, do so with those who will build lifeboats with you.

Mike Ruppert gives what I feel is a pretty good analogy that works here, since we’re neck-deep in a myriad of crises including peak oil, climate change, and economic devastation. There are three kinds of people on the Titanic.

There’s the first who believe “The Titanic is ‘un-fucking-sinkable’ and while you doomers are out here I am going back to the bar.”

Then, there are those who panic and run around using a lot of energy but putting none into doing anything effective.

Finally, there are those who say “Well, we have x numbers of lifeboats. We fill them and make more where we can.” At the end of the day, the people who come together and build the lifeboats are going to make it.

“That’s what I’ve noticed anyway. People not stepping up and taking leadership roles…to best illustrate the point.)”

This is where I say that if you want to move the Pagan community in a direction, do so with those who will build lifeboats with you.

Mike Ruppert gives what I feel is a pretty good analogy that works here, since we’re neck-deep in a myriad of crises including peak oil, climate change, and economic devastation. There are three kinds of people on the Titanic.

There’s the first who believe “The Titanic is ‘un-fucking-sinkable’ and while you doomers are out here I am going back to the bar.”

Then, there are those who panic and run around using a lot of energy but putting none into doing anything effective.

Finally, there are those who say “Well, we have x numbers of lifeboats. We fill them and make more so we can live through this.” At the end of the day, the people who come together and build the lifeboats are going to make it.

Sometimes, I think that people forget that the various paganisms (small p deliberate) are not only very much distinct religions in their own right, but are also not political organisations. What is a major priority for one person within a particular religious group may well be a complete non issue for another within that religious group, let alone an individual from another religion entirely.

People need to stop pretending that there is such a thing as a monolithic Paganism.

The only anarchist philosopher — if I may be so bold as to apply the term to him — who makes any sense to me is the late Robert Anton Wilson.

I reread “The Illuminatus! Triology” for entertainment, but the parts at which I slow down and ponder are the parts where Hagbard Celine and/or others engage in debates concerning it. I have yet to sit down for a serious read of his lesser-known writings, but they are on my shelf or on my list.

Maybe my exposure is limited. I’ve met several Pagans who have become or have been anarchists. I’ve yet to meet an anarchist who became a Pagan.

I hold a perhaps arrogant view of Paganisms in general when it comes to social and economic dynamics. We have (the arrogant part) the closest and most consciously aware view of balance in our world, and the creation and accumulation of wealth is a dynamic of imbalance. That is the question to be answered by philosophy: where is the balance, and who pays for its lack?

Others share your esteem for Wilson, including an anarchist witch friend of mine who’s constantly trying to get me to read more of him. : )

I’m not sure if I became a Pagan or an Anarchist first. I was certainly an anarchist long before being a polytheist. But I’ve met several others who are recently Pagan, who’ve seen pagan beliefs as extensions of their Anarchism, just as I know lots of people who see Anarchism as logical extensions of their Pagan thoughts, particularly, as you say, on the matter of balance.

I’ve met several […] who’ve seen pagan beliefs as extensions of their Anarchism, just as I know lots of people who see Anarchism as logical extensions of their Pagan thoughtsI totally respect that. I hope you can see that there are some Pagans out here for whom a government with the strength to care for the helpless and defend the environment is utterly consistent with their Paganism.

Absolutely. Which is why I don’t understand why they support the governments they’ve got. That, alone, should be enough to make them consider Anarchy, or Socialism at the very least.

I personally am not involved with polytheism but am involved in Nature-based practices. I had often found it strange how much of Paganism self-describes itself as Nature-based practices yet has a lot of consumerism with the items used to practice their paganism. There are so many products out there to perform what ever ritual you have in mind that is seems excessive and comes across as a marketing scheme. The witches in the Disc World series written by Terry Pratchett always come to mind when I think of this sort of things, “It had taken many years under the tutelage of Granny

Weatherwax for Magrat to learn that the common kitchen breadknife was

better than the most ornate of magical knives. It could do all that the

magical knife could do, plus you could also use it to cut bread.”

I always strive to ensure my personal practice is manifest in our world by doing public work projects, like the school garden, and a pilot project on a local farmer’s property. I also share a lot of what I know so that others can create positive change in their environment – writing at Patheos in the blog Paths Through The Forests. I show how you can manage the water on your landscape to prevent floods, droughts and fires; Help reveal the impacts of how we source the things we use, the impacts of how we do things, and the solutions for them; How we can garden with how nature works instead of against it in a food forest garden – not just organic. I often pose questions of how our practices can be a reflection of how nature works, especially as we come to understand it more, instead of going by what has been historically done even though we now know differently.

I greatly admire your work, and I should be clear–polytheism is hardly the only radical/revolutionary strain within Paganism.

There’s as much liberation in showing people how to grow their own food as their is organizing a manifestation against Capitalism–in fact, Capitalism is predicated on the divorce of humans from the rest of the living world, with the only approved method of interfacing between them being “the market.” Showing people you don’t need a grocery store to eat, you don’t need to buy vegetables and herbs that our growing right outside your door, weakens the very logic of Capitalist hegemony.

More so, showing that all Western Capitalism’s so-called “progress” (factory farming, bottled water, and an over-abundance of useless trinkets in stores) is actually not progress at all severely undermines the spell we all seem to be under.

And besides, we’ll all need to learn how to do that stuff again. And soon. 🙂

I flipped a coin. I couldn’t decide on whose post to put this one, both you and Rhyd are making such important points.

I take a “middling” position, certainly out of my upbringing and personal experiences. I am fully embedded in our modern society and culture, but I do not blithely or blindly accept all of it.

The middle way is the opposition of two things. We are losing the cultural value of what it means to have enough. It is being replaced by the notion (fallacy, I am asserting) that more is always better. Corporate greed, something we can see was always there in some form — if less visible in the past — is driving this shift, and we are powerless to stop it completely. Efforts like yours are how it will be prevented from taking over, and in my local and differing ways I stand with you against it.

Few of us are situated to grow our own food in meaningful quantities. We instead put our support behind the CSA movement, and buy our produce from local farmers at local outdoor markets. We don’t agree that it’s more expensive, not when we are assured by the farmers themselves, looking us in the eyes when they say it, that they are truly organic in their farming. There are more ways to measure this than dollars and cents.

Besides, no chain market I know of will stock fresh garlic scapes for any price. That is my reward for supporting local farms, and I’m enjoying it with every meal I cook. 😀

You know what sucks? Have no garden to speak of and not enough money to buy anything other than the lowest priced supermarket food.

It goes beyond food, though.

I spent the last year (re)training as a carpenter (I have two more to go), but I find that I can’t buy the timber as cheaply as I can buy the finished product elsewhere.

When people are already struggling to pay for the cheap crap they are getting, how do we move onto the good stuff?

Yours is a sadly common complaint, one to which I don’t have a ready answer. Much depends on finding others in your situation and banding together to find alternatives, something I’m not in a position to guess might be practical for you.

What may work for you is a potted garden or the before mentioned Kokedama. What ever you buy from the store, the food scraps can be regrown to produce the seed. Collect those seeds and then plant them to grow the food you desire. The fruits have seeds that can be collected and planted in your pots. Citrus plants can remain happy in a pot. Most other shrubs and trees would need to upgrade to bigger pots or transplanted once they are a year or two old. At this point, if you don’t have any yard, you can guerrilla garden. Meaning you plant it on a public or obviously unused vacant lot. Some have taken to utilizing the space between the sidewalk and road in front of their homes. There is also the option of grafting fruit tree branches onto the street trees put there by the city. I’ve read that guerrilla gardening is simple in the city because all you have to do is wear a worker vest and hard hat and nobody asks questions. I’m in a small town so I just go out in the supper hour when there is less people, but not as suspicious as working at night.

My plan is long term. A less than ideal situation now, gain trade, save money and improve situation later.

Once we have run out of oil there will no longer be as much cheap, new stuff ’cause it is being made from plastic. Barter and Recycling building materials are options. Regarding food: Gleaning (Many farmers are now allowing folks to come in and glean produce that remains after harvest–and that is tons of food! But be prepared to handle pesticided and herbicides.) Dumpster Diving (some supermarkets throw out fresh vegetables that are fine to eat, I have heard but never done this myself.) Being friends with gardeners can provide one with fresh veggies in the summer. Joining a community on the land can, too. May all the fresh veggies and fruits you need come to you, Blessed Be!

“Few of us are situated to grow our own food in meaningful quantities.”

Here is the kicker, there are increasing examples of food grown in abundance on smaller lots – usually coined as urban permaculture. The most popular example is the one urban farm that has been able to grow 6,000 lbs of food on a 1/10th acre. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCmTJkZy0rM

Apartment dwellers are growing their own food with window farms and aquaponics. There is also the little known Kokedama (hanging balls of moss to grow herbs and shrubs) that would do very well in a apartment.

Not that you should feel pressure to do any of these things, and supporting an CSA is an excellent way to go too. This is just to show that it is possible grow food in meaningful quantities, what ever the situation you are in. These are options that are definitely available to you. 🙂

I sometimes wonder just what the ancient urban Greeks and Romans would have thought about being called “pagan”, when they, themselves used the term, somewhat disparagingly to describe the “nature loving” rural dwellers.