The oldest house in town is not necessarily looking for attention. In contrast to some of the more lavish, well-known historical properties in the city, artfully restored Victorians that often function as bed-and-breakfasts or historical museums, the Daniel Christian house sits quite unassumingly on a quiet residential block just south of the downtown core, a mile or so inland from the Willamette River. The house blends in nicely amongst the curious variety of dwellings that surround it, and to the average passer-by, there is little about the house that suggests any historical or architectural significance.

I must have walked or biked past the house dozens of times without ever noticing it, until one day when a kitten stopped me in my path on the sidewalk in the middle of the block. I reached down to pet it and it ran up the porch step, daring me to follow. I stepped up onto the porch, scooped up the kitten, and found myself suddenly taking in my surroundings. This porch had a very different feel than the other houses I knew in this neighborhood. It felt… old. I glanced at the front door and noticed a sticker on the door stating that the building was on the National Register of Historic Places. There were four mailboxes next to the front door, indicating that the house was divided into residential apartments. I put down the kitten and thanked it for leading me to the front door. At that moment, one of the tenants walked up the porch steps and took out his key. I asked him if he knew the history of the building. “Its really old,” he said, obviously uninterested. “I don’t know much more than that.”

Daniel Christian House

I snapped a photo of the house and walked a few blocks to the Lane County Historical Society, showed the photo to the woman behind the counter when I walked in, and within a few minutes I learned that not only was the Daniel Christian house the oldest remaining house in all of Eugene, but it was most likely the only frame house left standing from Oregon’s territorial era. Christian and his family arrived in Oregon in 1853 from Illinois and settled on a 209-acre donation land claim, a footprint which is now the heart of Eugene’s midtown business district. The Greek Revival-style farmhouse that bears his name was built by Christian himself in 1855, nine years after the city of Eugene was founded, and the surrounding land served as an apple orchard up until the turn of the century.

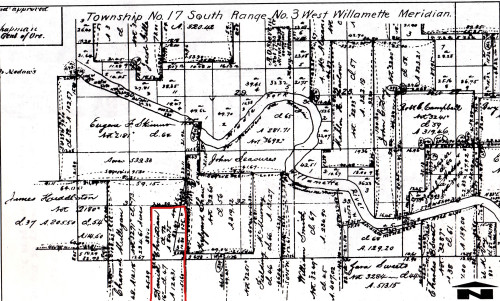

I left the Historical Society with a photocopy of a cadastral map from 1860, showing the original donation land claims that formed the City of Eugene. As I walked back to the house, I reflected on the fact that the dense urban neighborhood that I was passing through had once been an apple orchard anchored by a small, simple farmhouse. A significant portion of the land that was once Daniel Christian’s orchard is currently the site of the largest development project in the city’s history, a project that went forth despite sharp opposition from the community, and as I walked past the development I couldn’t help but to think that an apple orchard in that location would have been of much greater benefit to the neighborhood. I arrived back in front of the house, a house which I now knew had been standing for 158 years, and tried to picture in my head what it must have looked like standing alone, surrounded by farmland, with a clear view straight to the river.

Within that visualization, I immediately noted the fact that the Daniel Christian house was a good distance from the river. The yearly, variable flooding of the Willamette had been a persistent problem throughout the city’s history, especially for the early settlers. The original 1851 Eugene city plat had to be revised and moved inland after the first year due to flooding, and subsequent floods wiped out early settlement areas time and time again. As the town grew over the years in size, the property damage from each flood intensified, until the federal government began to harness the river through a series of dams starting in the early 1940s. While the river still floods occasionally, the water levels have never reached anything close to the levels of the pre-dam floods, and flood damage in the modern day has been very minimal. Most current residents have no memory of a time when the natural rhythm of the floodplain greatly affected the use and development of the riverfront areas, and very few remember back to a time when residents had to be evacuated due to flooding. This lack of memory has always concerned me, even before I was ever conscious of how specifically vulnerable this area is to a flood-related natural disaster.

When I first started observing and taking in the layout and architecture within specific neighborhoods in this town, I had noticed early on that most of the houses and buildings anywhere near the riverfront were of more recent construction than most of the surrounding areas, with older houses farther back surrounding the newer developments. There are very few structures near the riverfront that pre-date WWII, despite the fact that some of these neighborhoods were originally platted years before that, in contrast to other neighborhoods in the city where a significant majority of the houses standing were built the same year the subdivision was originally platted. I had learned from an old realtor that many of the pre-war houses had been either built on beams to withstand the flooding or built without any sort of foundations whatsoever, and most of the houses that survived all the old floods have been since demolished. A bank won’t finance a home without a foundation, which made many of the old homes impossible to sell in the modern day. A few of these homes still survive, standing reminders of a time when the neighborhood was often underwater, but even these few survivors are disappearing one by one. And yet, I thought to myself, if a dam failure triggered even a temporary return to the river’s natural floodplain, those few old houses would probably fare much better overall than anything built in the last seventy years. I doubted that most of the inhabitants of those newer houses knew the history of the land that their house was built on, despite the subtle clues in the surrounding architecture.

This bungalow (left), built in 1930 at the edge of the natural floodplain and lacking a foundation, was put up for sale last spring and then demolished last month (right) when a cash buyer could not be found.

Standing in front of the Daniel Christian house, I reflected on the fact that this house had survived every flood from the time it was built up to the time the river was dammed. Hundreds of buildings were destroyed or washed away by floods over that hundred-year period, but this simple, inconspicuous house withstood them all. With flooding on my mind, I took out the donation land claim map from 1860, and as I found the location of the Christian land claim on the map I noticed something striking. The bend in the Willamette as drawn on the map did not match the current course of the river. While the current path of the river bends slightly north as it approaches the downtown area, the 1860 map illustrates the river sharply meandering north well past its current boundaries, channeling through a patch of land just above and over the present-day location of Autzen Stadium. I had heard it mentioned once that the flood of 1890 had altered the course of the Willamette, but I hadn’t a clue as to the location or severity of that alteration, and I had never given it much thought until that moment.

1860 Donation Land Claim map, illustrating a sharp river meander. The Daniel Christian land claim is outlined in red.

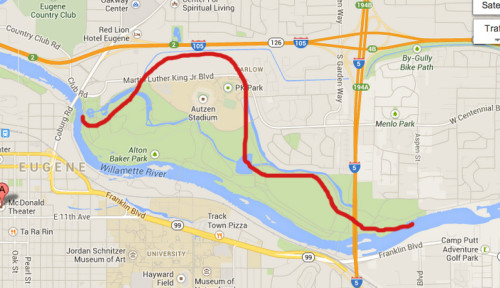

I took out my phone and pulled up a satellite map of the area, and compared the path of the river to the illustration of the 1860 map. In quickly tracing past and present shape of the river, suddenly the history and composition of the land in between the two paths made perfect sense. The 1890 flood had altered the channel at the point of the meander, cutting off the meander and forming a shallow oxbow lake around the river’s old path. Evidence of this former river channel could be seen on the current satellite map, in the form of ponds and sloughs still in its old path. I had already known that the land under and around Autzen Stadium had been undeveloped swampland that was previously used as a dumpsite, but why that swampiness existed in the first place was now clear. The swamp was created by the oxbow lake after the river changed its course.

Current map of downtown Eugene and the Willamette River. The red line indicates the location of the river channel prior to 1890.

I left the house that survived a hundred years’ worth of floods and proceeded towards the river in order to trace the river’s old path. I had walked and biked through the exact area countless times before, but my knowledge of the river’s past spurned a new sense of curiosity about the ponds and sloughs that once cradled the Willamette itself. Following the waterway, I tried to ignore the presence of the looming stadium as I followed the water, envisioning the river, the flood, and the swamp. I suppose it’s fitting, I thought to myself, that a team called the Ducks play in a stadium built on a swamp.

Although I’ve thought for years about the Willamette floodplane and the harnessing of the river, only recently have I really thought about the potential devastation to this area in the wake of a natural disaster, and tracing the pre-1890 path of the Willamette brought that reality home for me. Hurricane Katrina was a tragic modern lesson on the vulnerability of dams and levees in the face of a storm, a lesson which greatly raised my own awareness of development and disasters in relation to floodplains. During Katrina, the greatest amount of devastation occurred in the low-lying areas which were not fit for widespread development prior to modern engineering, engineering which in the end could not stand up to the power of nature. If dam failures allowed the Willamette to rise to its natural level, the greatest potential for devastation would also occur in the low-lying areas that were developed after the river was dammed. During Katrina, evacuees took refuge in the Superdome, which had been built upon higher ground. But in the event of a flood-related disaster in Eugene, Autzen Stadium may very well be underwater.

In 1890, the river changed its course on its own and significantly altered the natural landscape without any help from a natural disaster, and scientists have warned for years now that a natural disaster in this area is only a matter of time. The Willamette Valley sits atop the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which experts say is over a hundred years overdue for a major earthquake. In the past few years, concerns have been raised by scientists, journalists, and politicians about the potential of catastrophic dam failures on the Willamette and/or widespread devastation in the event of an earthquake or a tsunami. Although the Japanese tsunami of 2011 sparked a certain degree of awareness as to the vulnerability inherent in our location and infrastructure, little has been done overall to prepare for such a disaster on a local level. Public meetings are held to discuss the economic viability of long-term riverfront development projects as though our dams are impervious to the ways of nature, while no real time or effort is ever spent discussing the overall viability of the city itself in the event that even one of those dams were to fail. While information and education about the level of risk is occasionally available to those who deliberately seek it out, many members of this community are completely unaware of the likelihood of such a disaster occurring here as well as the severity of the impact that such an event will have.

I thought of the tenant I met outside the Daniel Christian house, who was completely uninterested as to the history of his own building. In the case of a low-level to moderate flood, he is most likely protected in his ignorance, as he just happens to live in a house that has withstood every flood in the city’s history. But if a major earthquake hits, triggering the 40-foot wall of water that experts fear it will, he will literally be in the same boat as the rest of us, no pun intended.

Many of us look to the land to teach us various internal and external lessons. And most of us look to what has been built before us in order to better understand who we were and are. But we sometimes overlook the idea that the objects and structures that we have built can also serve as powerful lessons about the land itself. Lessons that our ancestors knew but in the present-day we have forgotten, lessons that the land may not be able to tell us quite so clearly, especially when man-made alterations have transformed the historic layout of a landscape. The Willamette River, currently held back by over twenty dams, has been muzzled and cannot presently hint at the potential reaches of her natural floodplain. And yet the historic age of the buildings and their relative distance from the riverfront illustrate that reach in a way that the river cannot. Perhaps more significantly, the Daniel Christian house serves as an important physical marker, speaking to the boundaries of how far the water has risen in the floods of the past. And yet, while I am slightly comforted in my knowledge and understanding of the reaches of the natural floodplain and the history of the land, I also know that an earthquake-triggered flood may very well result in a flooding situation that will render these observations and lessons irrelevant. But at least I am aware of this inevitability, and I deeply understand that such a disaster is not a matter of if, but when. In the meantime, however, I am simply grateful for my constantly evolving relationship with the river.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

The magic in this is subtle, but powerful. As a local, I can safely say that I was ignorant as to just about every single thing you’ve written here. It makes me want to pay attention to my own surroundings much more, to say the least. Thank you for this.

The dams on the Willamette are horrific affront to the river’s ecosystem. They have greatly damaged the endangered native salmon and steelhead populations that use the river to spawn and raise their young.

The dams shouldn’t be there and should be removed. If you don’t like floods and their consequences, don’t build on flood plains.