I just got back from seeing the latest “witch” film, Beautiful Creatures. It is a supernatural love-story adapted from a popular young-adult novel of the same name by Kami Garcia and Margaret Stohl. The story tells of Ethan, a mortal boy, falling in love with Lena, a young witch, or “caster” to use the film’s politically correct term. Tension builds as Lena’s 16th birthday approaches, at which she will be chosen for either the dark or the light.

On my drive home from the theater, the wheels began spinning in my head – age 16, light vs. dark, young love. The narrative fits so perfectly into the allegorical language of Hollywood teenage witch caster films. My mind is still spinning.

For those of you who haven’t read my bio, I am a film scholar. I spent many years writing about the mediation and impact of visual imagery. The release of Beautiful Creatures has provided me with the incentive to dust-off an old dissertation proposal, Visual Representations of the Witch in Hollywood Cinema: An historical analysis. However, I can’t do this in one post. Over some indeterminate period of time I will explore the topic, in-between news outbreaks and other stories. I’m thrilled to see just what this work will conjure.

(One important note, for my purposes: A witch is a witch. A caster is a little wheel on a piece of furniture. )

A few weeks ago, Jason asked, “What does the witch do?” The answer to this question is complex because film art is complex. It’s a narrative form with a definitive language and particular mythology, which speaks to us through a variety of technical elements including; visuals, sound, and story. Each film production unit has a slightly different language. For example, India’s film language is different from France’s. American Independent films are different from Hollywood films.

So, let’s talk Hollywood. Since its inception, Hollywood has been an integral part of the American pop-culture paradigm, one that both reflects and informs our culture. Hollywood gives us what we want as well as attempting to shape our opinions. In the 1930s, musicals, such as Busby Berkley’s 42nd Street (1933), were an attractive distraction from the Depression. In the 1940s, Hollywood released war films, such as Flying Tigers (1941) or Casablanca (1943) , to encourage support for American involvement in WWII. Hollywood films are an excellent gauge of the “pulse” of the nation at any given point in time.

Casablanca (1942)

Photo Courtesy of doctormacro.com

Using an historically-based model, we can locate the witch’s place within Hollywood’s symbolic structure. However, before diving in, there is one very important piece of film history that is essential for understanding Hollywood iconography. Most viewers recognize the extreme conservatism in early Hollywood films, but most don’t realize that it wasn’t just happenstance. In the 1930s Hollywood made a deal with the Catholic Church in order to ensure its financial future.

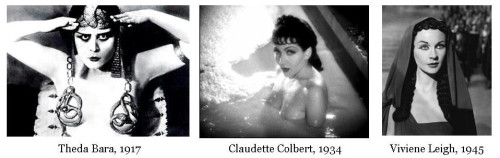

Prior to the 1930, Hollywood had absolutely no censorship and was free to show whatever it wanted, no matter how lurid, risqué or controversial. A good comparison is De Mille’s Cleopatra (1934) or Edward’s Cleopatra (1917) to Pascal’s Caesar and Cleopatra (1945). The early films contain more “skin” and expressions of sexuality than the latter. While the two older films may not be X-rated by today’s standards, they did push the limit within their own historical context.

Cleopatra

Photos Courtesy of doctormacro.com

By the late 1920s, the Catholic Church had organized boycotts and petitions to protest the perceived indecency in Hollywood films. As a result, in 1930, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) established a censorship standard called the Production Code and a watch-dog agency called the Production Code Administration (PCA).

The Code was meant to appease the Church and stop the outcry. After the Crash of 1929, Hollywood could not afford to lose patrons. Regardless, from 1930-1934, the Code had very little effect on Hollywood’s output. So, the Catholic Church increased its pressure by establishing its own motion Picture watch-dog agency, The Legion of Decency.

Together with other religious organizations, the Legion pushed the PCA into hiring an enforcer, Joseph Breen. As noted by Film historian Thomas Doherty, Breen had been a “diplomat and publicity director for Chicago’s 1926 International Eucharistic Congress, a World’s Fair for Catholics.” Breen and the PCA became involved in all aspects of production from writing to editing. Doherty explains:

Breen demanded that American cinema obey a strict catechism of thou-shalt-nots. More than any single individual, he shaped the moral stature of the American motion picture.

From 1934-1968, the PCA was charged with “keep[ing] patrons from movies which offend decency and Christian morality.’” On the one hand, the Code probably saved Hollywood from the Depression turning it into one of the only industries to thrive in the 1930s. On the other hand, Hollywood’s film language was shaped by this conservative Catholic moral sensibility. Doherty goes on to explain,

The code itself was meant to be almost Biblical, metaphors of print-based religiosity would waft around it like incense: the commandments, the tablets, and the gospel.

As a result, a highly-codified film language was born. Here are just a few examples of the religious-bias written into the Code either directly or indirectly through language: (Read more of the Code here)

Pure love, the love of a man for a woman permitted by the law of God and man, is the rightful subject of plots. The passion arising from this love is not the subject for plots.

The name of Jesus Christ should never be used except in reverence.

The effect of nudity or semi-nudity upon the normal man or woman, and much more upon a young person, has been honestly recognized by all lawmakers and moralists… Hence the fact that the nude or semi-nude body may be beautiful does not make its use in films moral.

In the end the audience [must] feel that evil is wrong and good is right.

Over time, the Code broke down due to competition with television and the onset of the Cultural Revolution. By 1968, it was replaced by our current age-based rating system. But the underlying Catholic sensibility had lasting effects. For example, we still have movies with very strong good-versus-evil themes, as represented by Beautiful Creatures.

Wizard of Oz (1939)

Photo courtesy of doctormacro.com

Where does that leave the witch? Early on, she* was saddled with a stigma common to any Catholic-based mythological system. As such, she is absent of any meaningful theology, other than the residuals from Christianity. In Hollywood, she is a fictional or mythological creation. She is not us – or those of us who identify as such. While our paths may intertwine and even have common historical roots, we aren’t the same. Why? In Hollywood mythology, the witch is not real.

Has that changed or evolved? Now there’s my cliff hanger, to coin a Hollywood expression. We’ll see where this study leads. In the end, it may prove that not only does the witch inform and reflect mainstream culture, but she may inform our culture and how we, as witches, define ourselves.

To Be Continued…

*Using “she” for ease of explanation at this point.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Thanx for a good bit of background before you get deeper into this. It’s amazing how interesting and provocative (for the time, but sometimes even by today’s standards) many of the “before the code” films were.

Outstanding beginning! Can’t wait for more!

I am definitely looking forward to the rest of this series. 🙂

On question, though: I have not seen “Beautiful Creatures.” Did the characters perhaps mean “caster” instead of “castor?”

Good question, because my thought on reading that was that word “hollywood” wanted is “caster,” a person who casts…..whatever. The word “castor” brings to mind Castor Oil and the aforementioned beavers.

I have a copy of the book and the spelling is definitely “caster” not “castor”.

My thoughts exactly, Lyradora.

Or the little wheel on a furniture leg. 🙂

No, it’s “caster” as in spell-caster, as others have noted.

MTE, was wondering whose spelling error that was, the OP or the book/movie. (Also, for anyone who plays MMOs, you hear “caster” all the time. “Two melee, three casters.”)

Yes. Thank You. The spell “caster” is correct. I did not have the book and was going off a film review spelling. I am making the correction so it doesn’t detract from the rest of the article.

When I was a kid, 50+ years ago, the Legion of Decency ratings were posted on the wall at my Catholic elementary school, and published in the Diocesan newspaper all families were semi-obligated to subscribe to. Boy, I really wanted to know what was in those movies rated “Condemned”!

When I was a teenager in the Fifties I had a Catholic buddy who introduced me to the Catholic Universe Bulletin which served just the function you describe in the Cleveland OH diocese. My adolescent mind was bemused at the reduncancy of LoD effort; didn’t Hollywood already have a ratings system?

Today my wife is the family cinephile and favors movies of the Thirties and Forties. I am forced to admit that the industry produced some excellent product even while coloring within the lines set by the censors.

And I insist “censor” is the right word, not “industry standards.” Movie/TV ratings are promulgated by the industries under the threat of government censorship as an alternative. The human sock puppets who run those systems are at the height of hypocrisy when they claim to be protecting the industry from government censors; they are government censors.

Wow, it would be cool to see one of those “bulletins”.

Is there anything that Christianity can’t fuck up?

Leoht: LoL

Jason: OT: RE: BBC on #of RCC’rs http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21545819

Heather, it was great to connect with you last week over dialogue issues. I had no idea you worked in this area, a passion of mine in cinema and genre in pop culture. I’ve explored aspects of Western esotericism in cinema, and in particular conceptions of the witch, at my blog TheoFantastique. Peg Aloi has been a dialogue partner. Here is an example: http://www.theofantastique.com/2010/12/19/peg-aloi-season-of-the-witch-2011/, and you might also poke around the site for our podcast on The Black Death. I look forward to your future installments on this topic.

“Beautiful Creatures” looks a whole lot better than “Hansel & Gretal: Witch Hunters”. This could be what “Practical Magic” was, a witch movie for a whole new generation. However, the trailer does have a bit of a “Twilight” feeling to it.

The PCA code is responsible for hundreds of adaptations of books in movies being butchered to satisfy self appointed tin plated moralists. That the grubby bloodstained hands of the Catholic Church was behind it does not surprise me.

It’s truly a shame the USAAF didn’t manage to accidentally drop a few dozen bombs on the Vatican City when they bombed Rome in 1943-44. Only the RAF and the Luftwaffe managed to do that but not nearly enough.

I think it is also important to look at how the Witch, in history and film, has been demarcated from society on a myriad of levels in terms of depiction. On one level, you have a separation dialectic (us/them, good/evil, and a reverse of this with the concept of Good Witches). And, too, it is interesting to note how Witches view “non-magical” folk. I have heard “Mundanes” being used, as well as “Muggles,” as well as “Cowans” or those uninitiated in the Mysteries, etc. The use of these terms, I think, highlights much in the Witch wordview, an depiction (fiction/non-fiction). There are many ironies, turns, and overlapping elements involved. Just a few thoughts 🙂