This week has weighed heavily on me. As the mother of three school age children, I spent this holiday week in-and-out of classrooms. With the Newtown tragedy still fresh, there was an underlying uneasiness within our elementary school – a profound sadness and unspoken fear. While I looked at all the children’s projects taped to the walls, one phrase kept passing through my mind:

“How could God have allowed that to happen?”

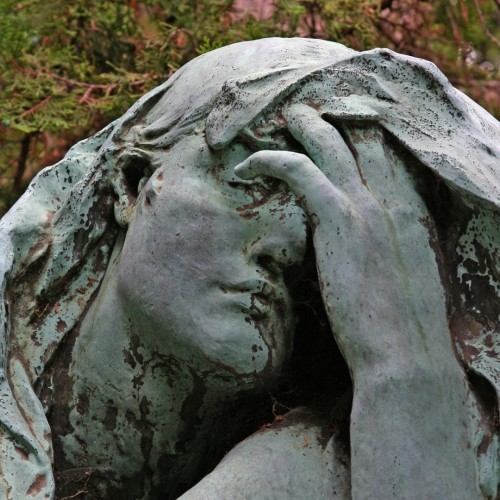

From Cimetiere du Pere Lachaise

Photo courtesy of Leo Reynolds of Flickr

You wonder how a practicing Pagan, a Wiccan Priestess could ask this question? But I’m not asking it. I’m hearing it. I’m reading it. Whether it’s spoken by neighbors or published on the internet, this burning question is drowning out much of the news reports and political calls-to-action as people desperately grasp for meaning.

I began to wonder how we, as Pagans, approach this question. Not for ourselves within our Pagan community but for others outside of our faith. How can we, as Pagans, talk to a depressed Catholic man who has recently lost his wife in a flood? How do we help a young Jewish girl find peace after losing her friend in a war? How do we calm a Methodist mother whose child has just been shot in a classroom?

Whether at a private memorial service or on the front-lines of tragedy, we all will be or have been put in the position to console the grieving. Given we are in a minority religion, there is very good chance that the grieving individual is not Pagan. How do we console someone who understands the Divine in an entirely different way?

Sandra L. Harris, M.Div., Pagan Pastoral Counseling

Several months ago, when I interviewed Sandra Harris, the master’s graduate from Cherry Hill Seminary, we briefly discussed this topic in relation to the Hurricane Sandy disaster. Aside from her work in hospital chaplaincy, Sandra was accepted to the Fairfax County Community Chaplain Corps, an interfaith first-response unit that “provides spiritual care and support to community members during and after a local emergency or man-made or natural disaster.”

I turned to Sandra this week to revisit her advice. She shared this:

When something happens none of us knows why, in all its details, cosmic or mundane. Asking the question [“Why?”] is a very normal human behavior. We count on the Universe to have some order, some predictability. The question arises because the Universe didn’t follow the rules and we fear there are other things we assumed to be true that maybe aren’t.

[As a Pagan friend, minister or confidant] our best response is one that, first, affirms the need and validity of the question and the questioner. Our second response is to encourage the questioner to talk with the aim of releasing what meaning he or she fears the event has. Finally, our third and most difficult job is to help the questioner re-frame the event in some way that leaves hope alive and allows meaning to grow from what happens next. This is where we walk with the questioner while the he or she questions the Divine. We just facilitate that conversation, gently reigning it in when it sidetracks down dark alleys, trying to steer clear from the “if only” and the “what ifs.”

In all cases, never take away hope, stay in the “here and now,” and never be so presumptuous as to impugn meaning to an event in another’s life.

Lady Emrys, Wiccan Priestess

Licensed Clinical Social Worker

Sandra’s thoughts were echoed by another Pagan minister, Lady Emrys, who is a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) with extensive experience in hospice and palliative care as well as psychotherapy. She has worked to ease the spirits of both grieving families and the dying themselves. For much of her career, Lady Emrys worked in the heavily Baptist Deep South with many of those years spent at St. Joeseph’s, a Catholic hospital in Atlanta. Her patients and clients are rarely Pagan. When I posed my question to her, she remarked:

When we sit with people who are experiencing this level of suffering, it’s not about what you say. It’s about how well you listen; how well you can create a space for them to safely feel and say whatever is in their hearts. It’s about how well you can stay present with them, when their pain is so difficult to witness, that all you want to do is fix them.

Whether as minister or as a friend, helping another in this capacity is no easy task for even the trained. Lady Emrys added, “On rare occasions [when] I had interactions with people who were nearly impossible to work with due to a combination of fundamentalism and personality issues, I partnered with another team member, especially the chaplain. This was always helpful in my own self-care and safety.”

In the end, whether the client is Pagan or another faith, in order to truly be present as both Lady Emrys and Sandra describe, we must step outside the barriers that separate our religions. We must journey far beyond interfaith constructs to reach a boundless space where only universal humanity exists. Lady Emrys reminds us:

Regardless of our differences, we are humans with similar needs and desires. If we focus on our similarities, on the compassion we have for our fellow human beings, the connection we make will cause those differences to become insignificant.

So, when they ask, “How could God have allowed that to happen?” We respond, “Well, what do you think?” And then, once there, we listen. Most importantly, Sandra Harris reminds us, “Silence is OK.”

Merry Solstice, Light the lights and may peace find you today and always.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Not all questions have an answer, and not all answers are the ones people want to hear.

Thanks, Heather. I’ve stood in four ceremonies this week in which this event has been commemorated or acknowledged–two of which I organized or helped to organize.In each one, I’ve invited people to look to nature for answers, for comfort, for renewal. When Pagans stand with their Abrahamic neighbors, we do bring something different to the mix and that difference can provide some comfort, I think, to all parties.

Heather, this is a beautiful article. Thank you for bringing your compassionate, mother’s voice to such a difficult subject.

If we accept the pan(en)theistic notion that ‘Thou art God(dess)’, one need look no further than Adam Peter Lanza, his family, and those who might have been his mentors or confidants for answers.

Manifest as Lanza, God was very likely autistic, was a social outcast, and was profoundly disturbed—possibly on account of the way his mother treated him. Manifest as those who had contact with Lanza, God(dess) elected not to reach out.

From what I’ve read, his mother was concerned about him, so it isn’t like she was blindly abusing him.

I didn’t assert that she was abusing him. I’ve read several anecdotes about his interaction with his mother; these seem to suggest that she was very controlling (perhaps to a much greater extent than was necessary, even in light of his alleged Asperger syndrome). For a young man, such treatment could prove to be as humiliating as (or more humiliating than) any interpersonal difficulties he might have met with on account of his condition.

I’ve read that she was/is a survivalist, which has garnered her some level of criticism.

As a professional chaplain, I concur with the article completely– provide a listening ear, show compassion, and affirm that we are all in shock and grief.

Every religion has weaknesses in their theology, and Christianity’s greatest Achilles’ heel, IMO, is the unresolved “theodicy” question. But during times like these, when people are hurting, it is not appropriate to debate theology. It is time, instead, to affirm that we are all grieving and the most helpful thing is to grieve together. This is when Interfaith work is about our common wounds and our common humanity.

In this moment, it’s not about giving answers, its about listening and caring.

As Stephen Levine says, “‘I don’t know’ is always the right answer.”