I blow the horn, and the mountains move in answer.

They aren’t mountains, I realize. The horizon shifts and rolls, and I am looking into the eyes of Jormungandr, the World Serpent, as its massive head swings down to see who has called on it. I can make out individual scales, the patterns of color in its great golden eyes, and I am delighted and terrified by its enormity, the sky-blocking size of it. My gaze lingers as the water in the lake around me drops, settling into a much lower level as the snake’s body rises. There are whole buildings in there – islands to explore in my own time.

I’ll worry about that later. Right now, it is just me, the jotnar before me, and the gods.

Three of them, specifically: Mimir, decapitated and revived by Freyja, hanging from a belt; Atreus, still young and not knowing his own true nature; and Kratos, the Ghost of Sparta, the murderer of Olympus.

I’m about ten hours into God of War, a video game released in 2018 for the PS4. This game series is known for its over-the-top gore and clever puzzles. I didn’t expect to be struck on my living room floor, with tears in my eyes. I don’t understand why there’s a heaviness in my chest, why I’ve put down the controller and leaned in toward the screen. I can’t explain this reaction.

Is this what “ineffable” means?

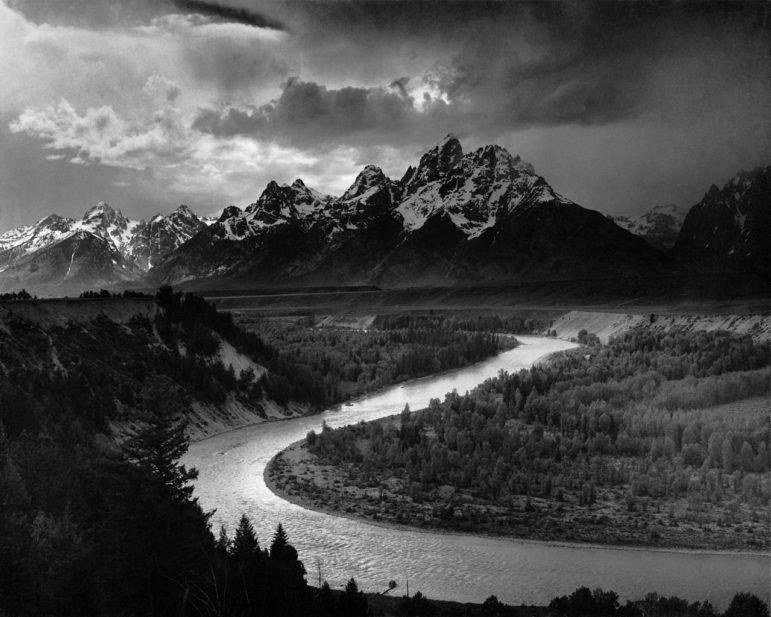

Ansel Adams, The Tetons and the Snake River, 1942 [public domain]

I couldn’t escape this game when it first came out. It seemed like everyone I knew – including the people who only barely understood that I was Pagan – thought that I should play it. Which was fair, honestly. I had played the first three games in undergrad, when my own faith was still something unnamed, and enjoyed them. They were set in a fantasy narrative that loosely overlaid Greek myths onto its characters, and I liked seeing the way they twisted the myths in irreverent ways. But that had been years ago, when I had much more time (and a current gaming system.)

The new game, which people seemed so intent on selling to me, wasn’t something I had any access to. I knew that it dealt with the Heathen gods, instead of the Hellenics, and I was pleased that my friends had thought of me. Then I forgot about it for a couple of years.

An image from God of War (2018) [Sony]

When I finally had a chance to play it this summer, I expected – well, a lot of blood, frankly. Maybe, if I was lucky, I’d get the chance to see some cool character designs for a moment before my main character killed them. That’s the idea of the franchise: the player is Kratos, the titular God of War. The plot of the first three games served, at least in my memory, as a paper-thin excuse for Kratos to fight, and eventually kill, every other god he encountered. I assumed that this would be pretty much the same. I’d fight my way through the three pantheons of Norse Mythology – Aesir, Vanir, and Jotun – depose Odin, and embody Ragnarok itself. A game about the end times seemed fitting, this summer. I thought I knew what I was signing up for.

What I got was something different. The game is still fascinated with the many and varied ways a body can be incapacitated, and it’s no spoiler to say that the plot revolves around death. Overlaid on that, unexpectedly, is a heartfelt narrative about cycles of violence, family trauma, and inheritance, a story straight out of a saga. And then, in the backdrop, a version of Norse mythology that was thoroughly researched, competently built out, and then twisted ever so slightly out of my expectations.

I want to be clear here – the writers take some liberties with the myths that are pure video game hijinks. Valkyries, the choosers of the slain, appear as corrupted and captured monsters that wait to be freed from their prisons. Some gods are combined. Others are written as abusers and tyrants. But the setting makes it clear that these are choices made by writers who know the myths, understand the gods, and have made specific changes in order to serve the story they want to tell.

One of those choices is to center the narrative of the jotun. Norse mythology is usually told from the point of view of the Aesir, a pantheon of “civilized” gods that, while descended from jotun, often see them as rivals or enemies. The myths are unkind to the jotun, so much so that one of the major doctrinal issues in Heathenry today is whether or not the modern Heathen should incorporate these spirits into their practice at all. Centering them is a smart move to flip the narrative, but in doing so, the writers also create a space for modern, thoughtful, and compassionate illustrations of a pantheon that are usually portrayed as the worst and most dangerous sort of outsider.

I work with the jotun quite a bit. Once I realized what the story was doing, I wasn’t surprised to find moments of gleeful recognition or even profound emotion in their stories. The story of Surtr in this game is one of sacrifice and bowing before fate – lessons I recognize from the jotun I work with. That means something to me, and it took me a while to realize that what I was feeling wasn’t just that recognition of a shared understanding. There were moments in the game – usually short ones, true, but distinct moments – where the mechanics and the nonsense plot fell away for a more direct experience. There were moments where I felt something I couldn’t name: something unmistakably religious.

Michal Klajban, Sun getting through fog in the New Zealand bush, Bryant Range, 2019 [Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

When people find out I’m Heathen, and realize what it means, by far the most common next step is for them to grin at me, tilt their heads, and ask, “What do you think of the Thor movies?”

The answer I give always seems to disappoint them. “I don’t think of them much,” I say with a shrug. “They’ve got all the same names, but I don’t know those guys. I love that people find their paths because of them! Just not for me. The Waititi one was really good, though.”

I remember staggering from an Old Norse final into the theater to see the first Thor and being really disappointed by it. I wanted to see the myths I knew, the figures I was starting to love, on the screen instead of these technicolor strangers. I couldn’t put a finger on what about them rang hollow and left me wanting more. I’d had moments of religious experience in media before, and from less self-important movies. Steve Martin and Martin Short as cartoon charlatans reciting the names of the Kemetic deities in Prince of Egypt had given me shivers since I was a child. Why that, and not this? What made something feel important? What made it echo in my chest and pour out of my hands and drive me to know more? What made it feel true?

I didn’t have an answer then, and I don’t have one now. I can only recognize it when it’s happening. The moment when Kratos opens the door to a temple and sees Yggdrasil, its branches stretching out into the many worlds – that felt right. When the game introduced Freyja, kneeling beside Hildisvini, she was unnamed and unmistakable. When I saw the architect of Asgard’s walls, killed by his own pick and big enough that his corpse was in itself a part of the terrain, I felt an ache for labor unvalued and broken oaths that I recognized.

At least the game named him. Jotnar in the myths very seldom have names. The writers called him Thamur, and his son Hrimthur. Those are names that I will keep, not because I think they are right, but so that when I tell the story I can tell it with respect.

Thorisjökull glacier, Iceland, 2005 [Chris 73, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

I want to tease this unnamable thing out, to tear each moment apart in search for the pieces that make it. How much of this experience is representation, seeing spirits I love treated with half-joking respect? How much is invocation, the writers calling on deities and getting more than what they bargained for? How much is narrative, a respect for sources that tries to treat moments of solemnity with the weight that their story calls for? Maybe if I measure each factor and weigh it out, I can find the right balance that takes something from cool to transcendent. It would be nice to be able to explain this, to justify it. “Yeah,” I’d say to the skeptical. “I had some strong feelings while playing this – but listen, it makes sense, they were so smart about-”

Every time I try, though, it slips away. I am left, a god far from his homeland, holding the body of my son and knowing he is holy, knowing I have harmed him, knowing that I will do anything to make him well again. I am left, a devotee in their own home, knowing this boy is my deity, and seeing someone familiar in the pain on his face.

I don’t have words for this feeling – but I know to honor it when I see it.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.