Editorial Note: The study described below refers to the practices of ancient pagan Britain; The Wild Hunt reserves capitalization in articles for modern Paganisms and practices.

A new study of the Thetford Hoard, one of Roman Britain’s most significant treasure finds and sometimes referred to as the Thetford Treasure, challenges long-held assumptions about the decline of paganism in the region. Published in the Journal of Roman Archaeology, the research by Professor Ellen Swift of the University of Kent argues that the hoard was buried in the early to mid-5th century CE—several decades later than previously thought.

Discovered in 1979 near Thetford, Norfolk, the Hoard consists of more than 40 luxury items, including gold finger-rings, necklaces, bracelets, silver spoons, a stylus, and a silver mirror. These objects offer a rare glimpse into the domestic life, personal adornment, and religious practices of Britain’s elite during the twilight of Roman rule.

Many items bear Latin inscriptions, Christian symbols, and classical Pagan imagery, reflecting a period of religious transition and cultural blending.

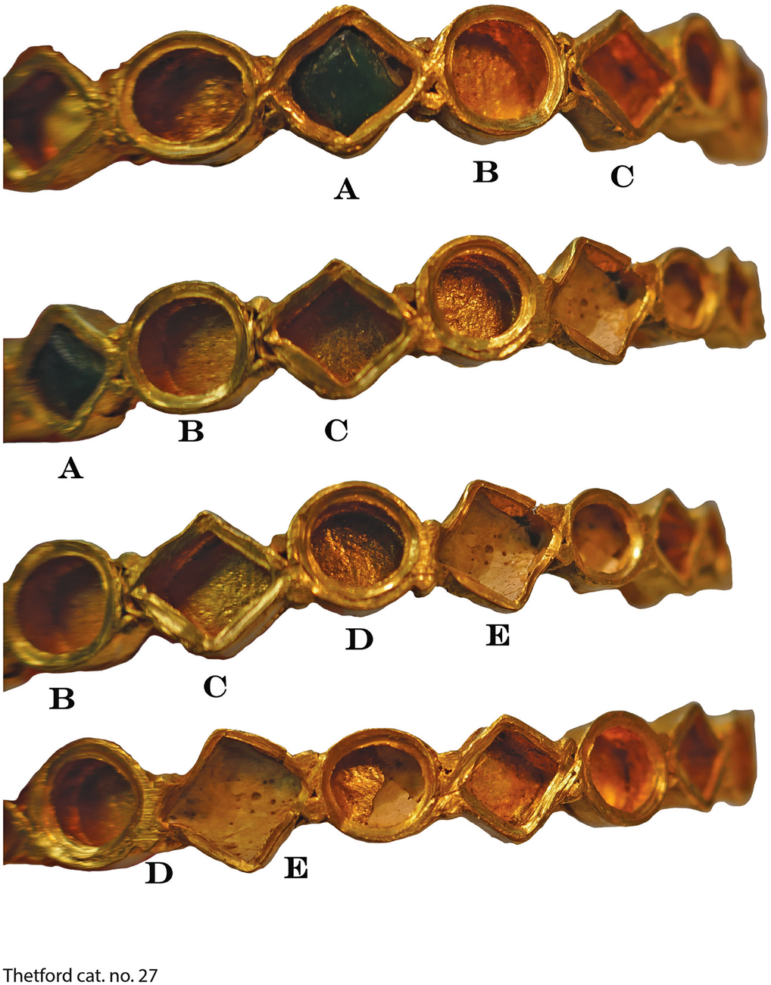

Thetford cat. no. 27 bracelet, with sulfur backing visible in gem setting E and the circular surround to its immediate right. Image Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0].

However, the hoard’s discovery was mired in controversy. Found with a metal detector and not immediately reported, the find lost critical archaeological context. Many objects were removed or possibly sold before archaeologists could properly record the site, complicating scholarly interpretation. Nevertheless, what remains is now housed in the British Museum and has been the subject of ongoing study.

For decades, scholars generally dated the hoard to the late 4th century CE, based in part on stylistic comparisons and the presence of late Roman coins.

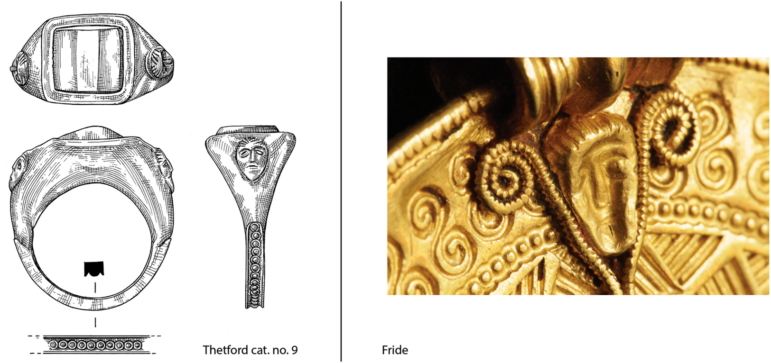

Example of ring decorations used in the analysis. left, left, (Image Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0]

Professor Swift’s re-evaluation of the jewelry and its wear patterns suggests a longer period of use. “There is compelling evidence that it was buried in the 5th century rather than the late 4th,” Swift told Cambridge University Press. “The site’s economic assets, indicated by the value and variety of the hoard, also show that it may have wielded significant power and authority locally.”

Much of Swift’s argument centers on a group of intricately decorated finger-rings with filigree spiral patterns—once considered among the latest-dating artifacts. While these rings do not offer a dramatically different date on their own, Swift contends they were in circulation longer than earlier scholars allowed. “Most of the evidence for wear occurs in this group of rings,” she notes, pointing to a broader usage window than initially believed.

The diversity of the jewelry’s origins further supports a 5th-century context. The finger rings likely originated in northern Italy, while a cone-shaped necklace suggests ties to the Lower Danube region. Despite these varied sources, the pieces share stylistic elements common to the Roman elite, implying that parts of Britain still participated in a broader Mediterranean culture even after the fall of centralized Roman authority.

At least 17 objects from the hoard match the materials, styles, and production techniques seen in 5th-century finds across continental Europe. Comparisons have been drawn to the Hoxne treasure—another late Roman hoard from Britain now also in the British Museum—suggesting broader patterns of elite behavior and continuity in the post-Roman West.

Swift argues that the hoard’s value may have increased in importance during its final phase, not just as personal wealth but as part of a local religious economy. “It is well documented that temples were a hive of economic activity. Religious foundations owned land and buildings that brought in income, and with it influence, in addition to gifts made to the shrine and fees for religious services,” she explains.

This revised chronology is reinforced by close comparisons between the Thetford items—particularly spoons and jewelry—and well-dated artifacts from continental Europe, as well as pieces from the 5th-century Hoxne hoard in the British Museum. The comparison strengthen the evidence from the site itself.

Earlier excavations revealed a large enclosure complex believed to have been an Iron Age shrine. Nearby finds—including coin hoards, shrine remains, and post-Roman timber structures—suggest the area retained religious significance into the 5th century. “Inscriptions on the spoons and other items indicate the site remained an active center of pagan worship during this later period,” Swift added.

Professor Ellen Swift also concluded that Britain was more connected to the broader Roman world than previously assumed, with items in the hoard originating from various parts of the empire.

“The Thetford jewelry especially is highly varied in style, suggesting the different pieces originated in different places,” she explained. “Some of the latest-dating finger-rings in the hoard likely came from northern Italy or nearby regions, and the necklace with conical beads appears to have originated in the Balkans.”

“Most of the jewelry is generically ‘Mediterranean Roman’ in style,” she added, “illustrating a geographically widespread shared culture among elites.”

Swift’s research suggests that instead of an abrupt end to pagan traditions, there may have been continuity well into the post-Roman era, with elite communities maintaining religious and cultural practices amid shifting political landscapes.

Despite the limitations imposed by its unreported discovery, the hoard remains one of the most luxurious and revealing finds from late Roman Britain. Swift’s reassessment invites scholars to reconsider assumptions about religious change and economic life at the edge of the Roman empire and the rate of adoption of Christianity in the region.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.