“Our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them.”- G. Eliot

I’ve always felt that the dead have a complicated life in Latin America. Although the Day of the Dead enters modernity through Mexico, the conversations and intimacy with death are profoundly embedded in and throughout Latino/Hispanic culture.

Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz once commented ““The word death is not pronounced in New York, in Paris, in London, because it burns the lips. The Mexican, in contrast, is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it, it is one of his favorite toys and his most steadfast love.” And it is much the same throughout the Latin world. Haitian Vodou celebrates Baron Samedi and the Guédé, the family of Loá that embody fertility and death. Brazil venerates Los Finados, honoring the dead and drawing on Christians as well as Indigenous traditions: the celebrations run from Bolivia to Cuba.

Santa María Magdalena de Pazzis Cemetery, San Juan. [Photo Credit: M. Tejeda-Moreno]

As an undergraduate, I remember reading Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude in a class on the modern fantastic. It is a seminal literary work on magical realism, a post-modern literary genre intertwining the natural and supernatural in mundane situations deeply linked to contemporary Latin American fiction.

I remember discussing the book in college and wondering why my Anglo classmates were reacting to Rebeca as a bizarre character. They were aghast. I thought it was her habit of eating earth. But, no, they cleared it up: she was carrying around the bones of her dead parents in canvas bag. And that was just too much. My reaction was “So? We did that too.”

Stares.

And I mean stares, the blank, horrified kind.

Lots of them. Hinting at grave digging is a conversation stopper. But, it was also true, at least as a family story.

My aunt – her name was Gladys but we called her YaYa, the term for “mother” in Palo, an African Traditional Religion – was much older than my father by almost twenty years. Because she lived to be 101, her memory spanned to a time before penicillin, running water, and even electricity. Every year in the first week of November, my aunt would instruct me that “the dead are respected but they are not feared. They will take advantage of you if they know you fear them.”

She would certainly know. When she was a child, one of her occasional tasks in November was to remove the bones of ancestors from mausoleums, then clean and place them in ossuaries. It was a practice that would die around World War I. But before that, burial of the dead was apparently a tricky challenge in tropical Cuba where the heat was a problem and space was a premium.

The practice at many cemeteries was simple: graves were rented, not owned. For about ten dollars (about 5% of annual household income), you would have a burial plot – usually above the ground in a mausoleum- for five years. After that time, your family could pay another $10 (or dig up and transfer the bones to chest that would be kept in the house. If you had no money to pay or “abandoned” the deceased, the bones would be disinterred and placed in a boneyard. One such boneyard is of the Colon Cemetery in Havana. There is a famous photo in the Burn’s Archive of Spanish American War soldiers holding human skulls and bones while standing on top of a 30 foot deep pile of human skeletons.

Therefore, for me as a college student, Rebeca’s bag of parental bones sounded like a practical solution to a financial problem. Rebeca’s story was neither horrific, nor alien. The conversation around death in many Latin American households is nonchalant. Death is not a topic of morbidity; only violent or untimely deaths are considered vulgar topics. Death is a reminder to live life fully not only as an act of the moment but as a collective act of preparing for death. But more importantly, perhaps it was that act that connected Rebeca to her forebearers in and intimate and immanent way.

Death in Tradition

Latin America is a fusion of traditions, and it just basically seems like the deceased can have a very difficult time not only navigating their own funerals, but also the complexities of the Afterlife. Native American, African and Christian faiths merged to create a culture where death is multifaceted: the rituals and the understanding of the nature of death are deeply rooted to ancient traditions that span millennia and are separated by oceans. Despite the number of professed Roman Catholics, Latin Americans are often raised in a space that sees and understands death in way that is neither fully Christian nor fully Pagan.

In the Yoruba tradition, Death is a purposeful celebration of the Balance. It is neither useless nor wasteful. In one pataki, death- called Ikú – was in Heaven and the world became overcrowded. The answer to the overcrowding was a cull of humans. So, Olofí – the spirit of God on Earth- ordered Oyá – the Orisha of the winds and change – to fly to Heaven and return Ikú to the world . She refused. Death for the act of slaughter has no purpose. When Olofi made Ikú part of the Balance, she gladly obeyed.

Orisha teach that death is simply another form of life. The dead- called Egungun – are revered because they are our ancestors. We cannot be here without the work of the dead, and they are still there to guide the living. But they have all the virtues and vices of their former life. If an ancestor was a drunk in life, for example, they’ll still like to drink. If they were generous with their time and opinions in life, they might choose to spend a lot of time with you, especially offering their continuous advice. It can be good or bad; but again it is intimate and immanent.

Ancestors can always teach, and we can always learn from their whispers, wisdom, and mistakes. To do that, we would set up bóvedas – altars that had glasses of water and candles carefully placed to denote balance. Sprigs of basil would be placed on the altar for cleansing to ensure that our answers were from our ancestors and that not from elsewhere. It is a ritual borrowed from Spiritism, and versions of it are found throughout the Latin World. Regardless of a professed faith – likely Catholicism- the practiced faith of many Latin Americans blends many traditions, reminding us to keep the dead close. And that is a practice, like Octavio Paz noted, that is far more alien in other parts of the world but deeply present in the Day of the Dead.

But then, a few weeks ago, I found myself surprised. When googling “Latin American Death Traditions,” I discovered “Santa Muerte” consistently appearing at the top of my searches. It is not that I had never heard of this entity; she came up while researching a different story several months ago. However, given the breadth and complexity of traditions throughout Latin America, it seemed odd that she would rise to such importance when researching death rituals. Because, bluntly most of us had never heard of her 20 years ago. And there’s so much more to death in Latin America than this one “saint.”

Santa Muerte is Spanish for “Holy Death.” More correctly, she is called Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte (or Our Lady of the Holy Death). She is a non-canonizedm folk saint who is venerated in parts of Mexico and United States. She is depicted as a skeletal figure often carrying a globe and scythe, and is robed frequently, but not exclusively, in white, similar to the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church in one of Her Apparitions.

Santa Muerte has several eponyms including La Flaquita (the Thin One), La Huesuda (The Bone Lady) and La Dama Poderosa (the Powerful Lady). She is venerated by many individuals who experience societal marginalization and alienation; and she even has a shrine on Alfarería Street in the barrio of Tepito, an underserved neighborhood of Mexico City. But her association with delinquency is significant. Santa Muerte is often referred to as the “narco-saint” having been associated with violent and high-profile criminality. She’s even had cameos in the television shows Breaking Bad and Dexter.

But Santa Muerte is not connected with antiquity like Day of the Dead celebrations. In fact, she is completely unrelated to the Day of the Dead. The holiday is a syncretism between Mesoamerican traditional faiths and the Catholic All Saints Day. There is even some documentary evidence linking to the celebrations of the Aztec nation.

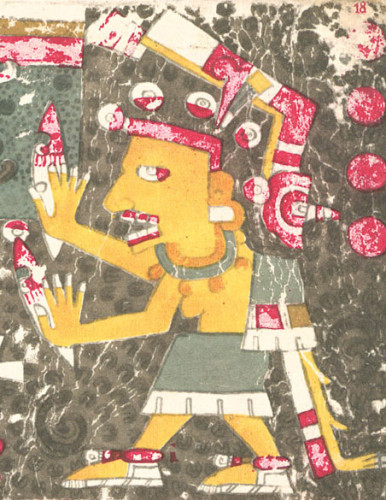

Mictecacihuatl, Queen of the Underworld

Mictecacihuatl [Public Domain]

The manuscript has a mysterious origin. It was essentially an unknown document until it surfaced in the 18th Century in Italy within the archives of Cardinal Stefano Borgia. Cardinal Borgia, by all accounts, was not only a minister and theologian, but he was also an antiquarian, publishing the first papyrus in the West documenting the maintenance and building of irrigation canals in Egypt. More importantly to our story though is his desires for acquisitions. His collecting of Pagan, Christian and Islamic papyri places him as one of the central figures of the preservation and archiving of such documents ultimately coalescing into the field of papyrology.

How Cardinal Borgia got his hands on this document is unknown. But his preservation of the document was a drastic contrast to that of his predecessors, the zealots who sought to abolish all traces of Pagan knowledge originating in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Beginning in the 15th Century, their nearly 400 years of sustained colonization and religious assimilation resulted in the destruction of many cultural cues and elements. But scholars have traced the veneration of Ancestors into pre-Columbian cultures (Miller, 2005).

The Codex itself helps the connections. It contains the elements of the Tonalpohualli, the 260-day calendar – and one of the two major calendars- used in Mesoamerica. This calendar breaks down into 20 thirteen-day periods. It is neither lunar nor solar and theories abound as to whether it aligns to a natural cycle or some abstraction within the Aztec mathematical system. But, the 10th period begins the cycle of the Dog (apparently more towards August than November), and that cycle is marked under the Lord of Mictlan, Mictlantecuhtli, the most prominent of the gods and goddesses of the Underworld and one of the Thirteen Lords of the Night illustrated in the Codex Borgia.

What is relevant to Santa Muerte is that Mictlantecuhtli had a wife, Mictecacihuatl. She is the queen of the Underworld (Mictlan) and the Lady of the Dead. Her job is to guard the bones of the dead and preside over the Mesoamerican festivals of the dead that likely evolved into the modern tradition of the Days of the Dead. Mictecacihuatl is depicted in the Codex Borgia and prominent as far back 200 ce. Her connection to the modern Day of the Dead festivities remains speculative. But one thing is clear; despite the cursory association with death, she has nothing to do with Santa Muerte.

The Rise of Santa Muerte

Santa Muerte’s rise in popularity has taken her from a marginal cult in the 1960s to conspicuous veneration in the 2000s. Yet, at the same time, she still exists in relative obscurity to many Latinos. She remains a divisive and controversial figure. The Catholic Church condemns her as idolatrous and nothing less than blasphemy. Her adoration is considered perverse and satanic.

In 2013, Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, President of the Pontifical Council for Culture, pleaded with Mexicans to halt her adoration, describing it as a “celebration of devastation and of hell.” In 2009, former Mexican President Felipe Calderon even launched military assaults on 40 or her shrines. But both of these were footnote events in Latin American news, which suggests that Santa Muerte’s fame may have one real catalyst: the media.

To explore that question, I spoke with Dr. Antonio Zavaleta, professor of Anthropology and Sociology at University of Texas- Brownsville. His area of research includes poverty, culture and economic activity along the US-Mexican border. This work has brought him to explore and publish works on ritual and folk-belief. He famously recorded the opening of magical work, which he disappointingly refers to as “Mexican Witchcraft,” and discusses ritual belief associated with statuary and intentional work.

While I understand his approach as an academic, the video is troubling to my personal sensibilities because I feel his objective of understanding the ritual work could have been accomplished without violating a piece of magical work. But the video does demonstrate the strength of devotion, ritual and will used to invoke Santa Muerte.

Dr. Zavaleta was generous with his time to describe how he had independently drawn similar conclusions about the rise of Santa Muerte. We talked about the complexity of the belief structure, and Santa Muerte’s rise in power and presence. His thoughts on the matter were the same: “faux-Catholicism fueled by the American media.” She may have some unlikely syncretism with Indigenous Mesoamerican and Catholic beliefs, but there is no “historical connection between Santa Muerte and the Day of the Dead,” he added. “The Day of the Dead is one thing. Santa Muerte is another thing” (Zavaleta, 2015).

Santissima Muerte [Public Domain]

But those audiences have one powerful thing in common: they are typically considered outcasts. She is said to be the protector of LGBTQ persons. She is venerated by the young, often women, and the working class. She is the protector of those people who must turn to work that is often deemed deviant, including sex work, begging and counterfeiting. And while her association with criminal elements seems probable, Santa Muerte is not defined by criminality (Peña, et al. 2009). Instead, she seems better defined by her unfailing support of the beleaguered.

Entering Pagan Space

I wrote that last sentence very carefully. Because in writing that paragraph, Santa Muerte seemed to change from an academic subject to an entity with purpose. I approached learning more about Santa Muerte as social phenomenon. But in doing so, I walked into a Pagan space. Our own traditions range from the reconstructed to the ancient. We, and I would say uniquely, understand that new and magical spaces can open at any time. That we hold keys to summoning new spirits as well as learning about old ones. The ancient and the new cannot only mingle, but they also add to our understanding of spirit. They can be venerated because the cosmos is not a static construction but a continuing revelation.

Santa Muerte is a patron of the disenfranchised to rise against the powers of order and oppression. She is an emotional backlash against the experience of marginalization. Her veneration remains strong among the groups who have been obsessively subjugated by a powerful patriarchy bent on conversion, control and humiliation. And these groups have little power, but she has entered as their ally.

Santa Muerte may be new, but she is no less immanent or relevant than any other Spirit, Intelligence, God or Faculty. The desperation of her followers, their rage of exclusion, and their rebellion to oppression have opened a potent emotional well where you can hear her murmurs with little strain. Pagans know that well. It has brought forth magic before. And I cannot help but wonder if it has borne a new goddess.

Citations

Peña, A. Alejandra, S. et al. (2009). El culto a la Santa Muerte: un estudio descriptive [The cult of Santa Muerte: A descriptive study. Revista Psicologica. http://www.udlondres.com/revista_psicologia/articulos/stamuerte.htm

Miller, Carlos (2005). “History: Indigenous people wouldn’t let ‘Day of the Dead’ die”. The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

Noguez, X. (2009). Códice Borgia. Arqueología Mexicana Edición Especial: Códices prehispánicas y coloniales tempranos.

Zavaleta, A. Personal communication. September 23, 2015.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

The number of the beleaguered, the disenfranchised, the poor, the people publically labeled and scorned as deviant, is steadily increasing at a rate not seen for centuries, as the present economic order collapses irreversibly. Once you realize this, the popularity of Santa Muerte ought not to surprise anyone. But yes, the Anglophone media, whoring after dollars, has found news of her to be a source of their profit.

What a fantastic, moving, and impressive piece! The World which lies like a bright shadow behind ours can, indeed, send another Being here at anytime.

I look forward to more from you, and thanks.

There is (or was about a year ago) a small store in San Francisco with a shop sign that is a painting of three identical female figures robed in white, red and black. At first glance I thought this was a shop catering to some syncretized LatinTriple Goddess cult, but the figures are skeletons and it’s all Santa Muerte inside the store. This is not a store for tourists.

She’s not *probably* associated with criminal activity, she *definitely* is, but certainly not exclusively. I’ve seen it a number of times in the last 20 years.