The dealer’s room at the International Congress on Medieval Studies – the annual medievalists’ conference that everyone just calls “Kalamazoo” – is a dangerous place, especially for me, a failed academic with discretionary income and no library access. Every major academic publisher with a medieval imprint has a stall there, hawking the latest publications in series like “Memory and the Medieval North” and “Toronto Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Rhetoric.” Because the Middle Ages have such popular appeal, there are some stands selling things besides scholarly monographs – manuscript facsimiles, drinking horns, and Green Man masks. And against one wall, standing behind his cases full of coins in silver, gold, and bronze, a numismatist.

I looked through his wares. I admired a silver penny from the reign of Henry II Plantagenet, the protagonist of The Lion in Winter, but it was almost $300 – a little out of my price range. A thought came to mind as I looked through the case’s collection of coins from France. “Pardon me,” I asked him. “This is a little out of period, but do you have anything from Julian II?”

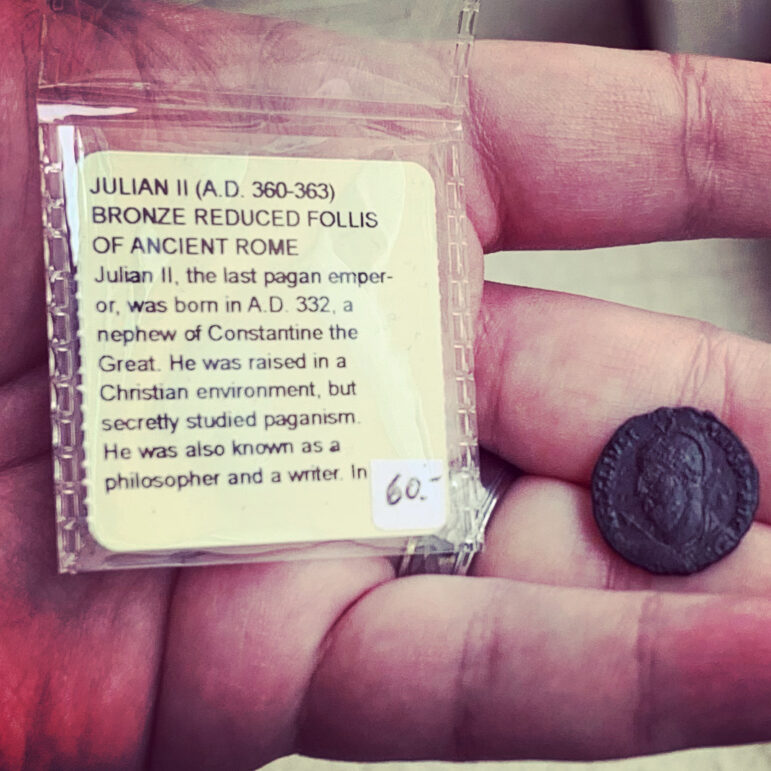

He pursed his lips and pulled out a small box of plastic coin holders from underneath the table. He rifled through them until he pulled out a bronze coin, small and dark, bearing the face of a bearded man. “This is the only one,” he said, “but it’s in good condition.

I held it under a magnifying glass and found myself staring at the profile of the last Pagan emperor, Julian the Apostate. It was a face I’d thought about often in my life; I’d written a book inspired by him in my 20s, and in the process, I had spent a lot of time thinking about what the world might have been like if Julian the Philosopher had reigned as long as his uncle Constantine. In the corner of the package was a handwritten sticker: 60 bucks.

I tried to buy it on the spot, but the coin seller only dealt in cash.

A bronze coin depicting Julian II “The Apostate,” the last pagan emperor of the Roman Empire. [E. Scott]

Artnet News reported last week that the most expensive ancient coin in history was sold at auction in Zurich this month. The coin is a gold stater, a kind of coin found in ancient Greece; this one dates from the 4th century B.C.E., when it was created in the city named Panticapaeum, which was near the modern city of Kerch in Crimea. For modern Pagan audiences, the coin is especially notable for its ancient pagan imagery; the obverse shows the head of a satyr, while the reverse shows a griffin holding a spear in its mouth.

The satyr’s face is exquisitely detailed. Unlike most coins, which show faces in full profile, this stater displays the face in a three-quarter profile. The face, according to The Art Newspaper, is thought to be a reference to the ancient Spartocid king Satyros I, who ruled from 432 to 389 B.C.E.

“The head of the satyr is a marvel of speaking portraiture,” said Godfrey Locker Lampson, an early 20th-century British politician who owned another coin of the type. “That so much expression could be packed into so small a round would not be believed by anyone who had not seen it.”

The griffin, on the other hand, is a guardian of gold deposits in the mountains of Scythia.

There are only three of these coins in existence, and the other two are already in museum collections. This coin had been part of the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia until the Soviet Union sold off much of its collection to raise money for industrial development. It was purchased by Charles Gillet, a French industrialist.

In the recent auction, the stater sold to an anonymous buyer for 5.39m Swiss francs, about $6 million. The previous record-holder for an ancient coin was sold in 2020 when a coin commemorating the death of Julius Caesar was sold with a falsified provenance for $4.2 million.

The satyr head face of the Panticapaeum stater [Numismatica Ars Classica]

It’s strange that there is such a thing as a “coin market” at all, really. The point of coinage is to standardize exchange, setting a fixed value that everyone in a polity can agree on. Especially when we’re discussing coins that derive most of their value from their material (unlike modern currency which primarily depends on the credit of an issuing state), it’s a little strange to think a coin that contains the exact same amount of gold grows so much in value just by virtue of the rarity of its design.

Although we don’t know the identity of the person who bought the Panticapaeum stater, I have to think that we have similar motivations, even if my purchase was $60 and theirs was $6 million. A coin marks a point in time in a way few other artifacts do. My bronze coin isn’t just a piece of metal with a Roman emperor’s face on it – it’s an artifact of his reign, a holdover from that era that testifies to what happened to that point and what might have happened if the contingencies of history had turned out differently.

I thought about those contingencies often as I wandered through the dealer’s room at Kalamazoo. I came to this conference most years that I was in graduate school, and spent a summer at this university studying Beowulf; I had even been accepted to the medieval studies program here when I was applying for masters programs. Sometimes I think of another set of circumstances in which I might have made a life in this city, at this university, in this career. It didn’t turn out to be this life, but I still like to check in on the life that might have been sometimes.

As for the Panticapaeum stater, I hope that whoever has bought it doesn’t hide it away in a vault somewhere. It’s too precious – in terms of both metal and memory – not to be shared with the world.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.