Holy wells and sacred springs have been part of the British landscape since long before recorded memory began, with our earliest evidence of worship at these sacred sites tracing back to the neolithic era. The near-universal sacredness of water meant that the oldest of these wells and springs passed through one religion to another, names and languages and rituals shifting down the years while their spiritual core remained the same.

These waters offered healing, broke curses, and restored fertility to their supplicants, many of whom made long journeys to bathe in and drink the waters, leaving behind offerings ranging from swords to strips of rag for the entities who gave the water its power.

Its important to note that the traditions varied for each site. Shared regional beliefs shaped common practices but even two sites located not far from each other, and in use by people from the same broader religious and cultural groups, often required different rituals, different offerings, and even wholly unique practices from those who sought their help.

The reason I bring this up in the midst of an introduction to a list of holy springs you can still bathe in in the U.K. is that there’s been a flattening of tradition over the years, as information and misinformation proliferates online. Local practices are erased as ideas about the one true, universal way to worship take hold. The Calleach’s Herbarium goes into more detail on how this is impacting Scottish traditions in particular (a place where bathing in the springs was usually taboo as it would destroy the power of the well), and I advise anyone interested in water and water work to read it. It is important, should you seek out holy wells or sacred springs, to do your research into that site in particular, to make sure you understand the requirements of the spirits inhabiting its waters.

Of the ancient springs and wells that survived Christianisation, many have since fallen dry or been abandoned as the religious landscape changed once again with the Reformation, moving away from ritual and intercessor saints to a direct channel with the Christian god. Some, however, survive, and are still safe to drink from or swim in, even as our means of accessing their waters has changed beyond recognition.

Though there are few such sites that still allow full immersion bathing – all of them, strangely enough, along the East of England (to my knowledge anyway) – they’re all well worth a visit. Hopefully other ancient holy springs will be restored and reopened soon.

Buxton

One of the two Roman bath towns in Britain, Buxton was originally called Aquae Arnemetiae, named for the geothermal springs the town was built around and their divine patroness. Arnemetia is a pre-Roman Brythonic goddess we know unfortunately little about; no writing attesting her mythology or ritual practices survive. Even her name is in question, as Arnemetia, meaning “she who dwells beside the sacred grove”, seems more like an epithet than a true name. However, based on archaeological finds, she seems to fit the broader model of Celtic water goddess, offering healing through her waters in exchange for worship and the typical small offerings left at these types of site.

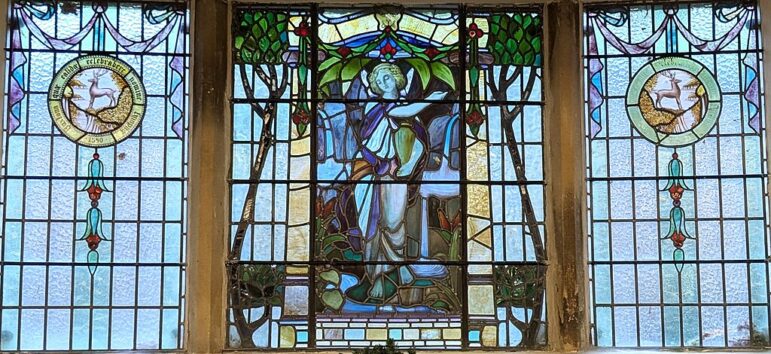

Stained glass portrait of Arnemetiae in the Pump Room [Douglal, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

After Christianisation, the springs became associated with St. Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary, allowing them to continue as a place of pilgrimage and worship into the Catholic era. Though the Reformation declared such “water worship” to be a demonic, un-Christian, pagan, “papish” practice (so many contradictory epithets at play), this particular belief never really took hold in Britain, and while the site at Buxton was closed temporarily under the new order it was reopened to seekers and pilgrims in 1572. This continuity of practice, combined with the natural warmth of her springs, left Buxton perfectly situated to blossom during the era of Georgian spa culture, when the (often pseudo) scientific approach to water cures largely replaced the religious.

That same geothermal heat gave Buxton staying power as the spa craze died down, with the baths seeing continued, albeit interrupted, usage over the last century and a half. Today there are two main locations for seekers looking to immerse themselves in the sacred waters: the wellness spa at the Buxton Crescent Hotel, which includes the original Victorian bath complex, and the town’s swimming pool near the Pavilion Gardens.

While a spa and a public pool may not sound like ideal spaces to commune with the divine, it’s actually a lot easier than it sounds, especially if you choose a time when few, or fewer, people are likely to be visiting alongside you. In particular, spa pools tend to be very good spaces for this, as spa goers tend to be quieter and less rowdy in the water while also giving each other a lot of space.

Though I haven’t had a chance to visit the Buxton Crescent the facilities as shown on the website look promising, especially as one of the pools is outside, and in my experience an outdoor setting usually enhances the experience.

Bath

Buxton’s more famous sister, Bath has a sacred history stretching back more than 8000 years. Said to have been founded by the legendary Brythonic king Bladdud during his time in exile as a swineherd, the story goes that he discovered the healing powers of the waters when he chased his pigs into the muddy spring and came out cured of the leprosy that had robbed him of his throne. On arrival the Romans turned the ancient cultic site into a thriving bath town, syncretising the local goddess Sul with Minerva, and naming their new settlement Aquae Sulis in her honour.

Roman Aquae Sulis temple complex in Bath, UK [Photo Credit: S. Ciotti]

Visitors didn’t just come to Aquae Sulis for healing. A significant cache of lead curse tablets was uncovered in the sacred spring within the temple complex, beneath the medieval King’s Bath which is still standing to this day. Carved into thin sheets of lead alloy, these tablets all fall into the “prayer for justice” category, with the inscription following a standard formula; the supplicant dedicates items of theirs that have been stolen to the goddess, rendering them now her divine property, and asks that various tortures from insomnia to infertility be visited upon them until the miscreant returns them to the temple. While healing is definitely the most prevalent gift Celtic water goddesses and well spirits are known for, cursing was also relatively common, with traditions varying widely by location – and not all as just or justified as those asked of Sulis Minerva.

Though the temple bath complex and the town itself slowly fell to ruin after the Roman withdrawal, interest in the spring’s healing properties remained. Then, with the establishment of a new town, now known simply as Bath, new baths were constructed under the auspices of the church, with brand new saintly patrons attached. After the Reformation there was a greater emphasis on the medical rather than spiritual benefits of bathing in the spring waters, something which no doubt contributed to Bath retaining its position as pre-eminent healing waters in Britain, surviving long enough to become the beating fashionable heart of the Georgian spa craze.

By 1978 all of the historic bath complexes in Bath had closed to the public due to a combination of safety concerns, lack of interest, and, in the case of the NHS, the construction of an in hospital hydrotherapy pool that was significantly more convenient to use than the Cross Bath. Though the Roman baths remain unsafe for swimmers, the Cross Bath, once used for hydrotherapy by the NHS, has been restored and open to the public since 1999 for a shockingly affordable price. Though the current building is 18th century in origin it sits over earlier medieval and Roman baths, and is officially recognised as a sacred site.

While I desperately want to immerse myself in the Cross Bath, it was unfortunately only available for private group hire on my previous visits to Bath, and so I had to content myself with its equally affordable sister location, the very modern Thermae Bath Spa, located just across the street. In addition to an indoor pool and the usual sauna and steam room and so on you’d expect from a spa, there’s also a lovely rooftop pool that looks out over the city, and it was there I discovered that you can in fact have a quiet religious experience in a swimming pool surrounded by other bathers. Because of Sul/Sulis’ connection with the sun, I recommend booking into either pool during the sunset and gazing at the the sky while floating in the thermal waters; it’s something I’ve done several times now and look forward to doing again when I have the chance.

There are also several very fancy hotels with their own private spas fed by Sul/Sulis’ hot springs; however they are eye wateringly expensive to stay in, and frankly, I think the Thermae facilities are better anyway. Obviously your mileage may vary.

Glastonbury

Often seen as the sacred heart of Britain in both Christian and Pagan spiritual paths, Glastonbury’s early history is a little less clear cut and well documented then either Roman bath town. Archaeological evidence shows that the area was subject to human use, including ritual, since the mesolithic era, though we know relatively little about the pre-Christian beliefs and practices of the region.

By Kurt Thomas Hunt from USA – The Holy Grail?, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=101314833

What we do know is largely pieced together from Arthuriana, in which shades of older belief are wound together with early medieval Christianity, creating an evocative patchwork from which it’s extremely hard to extract any sort of clarity whatsoever. Though early medieval Irish kingship is my academic specialty, when it comes to this sort of thing I’m not even going to try; there’s plenty of scholarship out there on the subject and I encourage you to read and draw your own conclusions. (I might end up writing more about this later. I can feel it coming for me now that I’ve said I won’t. But anyway.)

What we do have when it comes to Glastonbury and her two sacred springs is a mixture of Arthuriana and 19th and early 20th century Christo-Pagan mysticism that has since evolved into a living tradition, or more accurately several interrelated traditions, of their own. Of the two springs, the Red, otherwise known as the Chalice Well, is the most famous and, in my opinion, the most likely to have been venerated in ancient times as well as today. A chalybeate spring, meaning a water source with a naturally high iron content, the water from the Chalice Well has a red tinge, leaving reddish brown sediment in it. The frequency with which wells and springs were subjected to veneration by the Brythonic Celts and even earlier inhabitants of the region, combined with the evidence of ritual use of the Tor which looms over it, and the striking bloody residue it leaves behind, suggest to me that it’s unlikely not to have been seen as liminal or holy in some way.

Unfortunately, we can’t know for sure, but the later belief that the waters run red because Joseph of Arimathea hid the holy grail at the source of the spring, as well as the associations made by early English Christians between Glastonbury, the grail, St. Joseph, and Jesus’ alleged visit to Britain during his lost years, suggest to me that there was an older, pre-Christian tradition attached to the spring. The earliest evidence we have of healing powers being attributed to the spring is to be found in the late 18th century, Christian of course, and Glastonbury doesn’t seem to have had much success as a spa town. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, during Glastonbury’s development as a centre of alternative spiritual belief, that the Red Spring came to any real prominence, with the establishment of the Chalice Well Trust in 1959.

Today the Red Spring can be accessed in the Chalice Well gardens, where it flows from the well head down through tiered gardens of decreasing water quality – one to drink, one to bathe, and one to admire as it trickles from the final fountain to the garden’s end. The healing pool sits in a beautiful shaded area tucked between trees and rough rock walls, a space that thrums quietly with something numinous, and while the pool itself isn’t large enough to swim in, and the water is cold enough most people restrict themselves to paddling, it is possible for more than one person to lay fully immersed in the spring waters. I always feel particularly energised when I come away from the healing pool, though whether that’s the intense shock of the cold water or something more I can’t begin to determine.

Beside the Red Spring is the White Spring, which leaves behind a chalky calcite residue. The White Spring has never received the same sort of attention as its much more dramatic neighbour, and I suspect it may not have received any kind of sacral treatment during the pre-Christian era for that reason. However, it is also possible that its location beside the Red Spring led to it being seen as a balancing or counterpart site, especially as red and white both have Otherworldly connections in Insular Celtic myth.

In the last few decades the White Spring has been subject to greater care, with the old well house standing over it dedicated as a temple in 2005, and the spring, the shrines, and the healing pool inside it tended to by the Companions of the White Spring. Access to the White Spring’s temple is comparatively limited, and if you want to bathe in its waters its best you contact the Companions first to see what is and isn’t possible.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.