Editor’s note: This column references miscarriage and animal butchering.

I was at the craft store for something else, really.

The shop where I usually buy beads for devotional jewelry is classy, filled mostly with precious or semi-precious stones that I can select based on their associations and the unique colors of the lot they’ve been taken from. The bead kiosk at Michaels was a huge contrast. The beads I was pretty sure were stone were also, more often than not, dyed or treated into bright primary colors, and they were hugely outnumbered by the beads that were clearly glass. I was surprised to feel myself pausing with the back-of-the-head pressure that meant that somebody wanted an offering.

“Here?” I asked, and got a sense of excitement, a grabby-handed glee at all the pretty colors. I grinned, almost despite myself. “Okay. We can get a treat.”

I have never been a person who expected to have kids. Nieces and nephews, certainly – I enjoy hanging out with children just fine. But the patience and determination it takes to raise a kid, the equanimity to keep my temper calm and make myself a support and guide? It has always seemed to me an impossible task that only the truly called should attempt, and I’ve never been called.

So it was unexpected, to say the least, when my spirit spouse arrived in my life with a kid in tow. It wasn’t, until that point, even something that I had considered as a possibility. My spiritual life is a series of relationships, charted between and around specific personalities. I know my gods by their tone and their sense of humor and their varied opinions. They are ancient and vast, but they’re people with loves and eccentricities and different tastes. I am used to having a variety of people in my life – but reaching out to a new spirit who’s showing up and finding a child is jarring.

We picked out several strands of beads – bright reds, yellows, a string of glass eyes blues and pinks and lurid greens. That night, I spread them out on the table and made a very nice bracelet of reds and blues, patterned and handsome. I knew as soon as I tied it off that it wasn’t right.

“Did you want to do something else?” I asked, sectioning off another string. “I’m sorry. Shall we try again?”

The second bracelet was a riot. It clashed and repeated, using every one of the beads I had turned up my nose at in a patternless riff of color and size. I thought, several times, of trying to impose order – but there was such a glee about it that, by the time I tied it off, I was also grinning. I put it around my wrist and it looked back at me in glass eyes of purple and orange and black.

“I love it,” I told my step son. “I’m going to wear it to work.”

Polish medieval beads [Silar, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

Even in hard polytheist communities, where spirit spousing is a well-established practice and people share the details of their married lives, there’s not a lot of precedent for inheriting children. Certainly not young ones, the kind that like bright colors and being spooky, who still have the feeling of trying to figure out who they want to be.

“It’s not like I’m a full time parent,” I wrote on one forum. “But it’s definitely feeling like I have an opportunity to be a stable adult in someone’s life? The stuff he shares with me sounds like he doesn’t get a lot of that. Has anyone else interacted with someone who’s a kid before?”

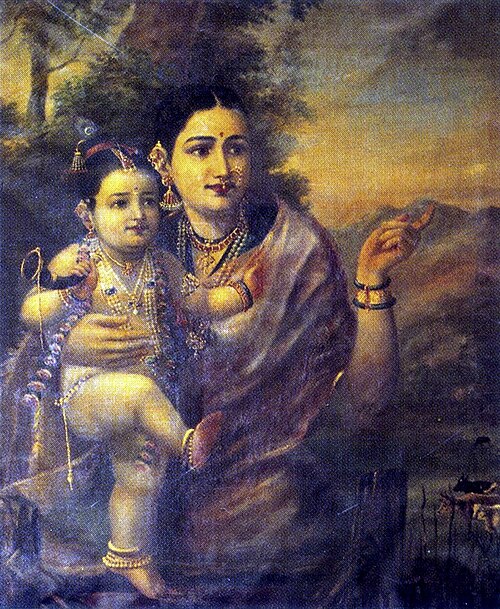

“Sometimes spirits are kids!” is the answer I got back. “Like the story about baby Krishna, where he eats the mud. It happens, but my spouse’s family all shows up as adults for me. Or they’re ageless.”

I’m not Hindu – and I know enough to know this person isn’t either – but I’m pretty sure that story is about how Krishna was still an all-encompassing force even when he was a baby. It feels different than the hurt-feeling tantrums and the hesitant, awkward attempts at affection I’m experiencing. But then again, I don’t even know how to make my own theology flex to allow for a spirit having developmental stages. I keep my mouth shut, and thank them for pointing me in a direction.

It’s not the first time I’ve run into the idea of interacting with gods in their childlike forms. Most of the gods I know have stories about being children, and I have no doubt there are aspects of them that still are. But my understanding of gods is that they can be many versions of themselves at once, and that by nature makes them bigger and more expansive than someone who is simply not very old. I realize that it is important to me that I believe my step son is exactly who and what he appears to be – which means treating him as the kid he’s showing up as, not some huge being presenting himself as a child.

Which means that, occasionally, I have a little dude in my house who likes big flavors and weird animals and colors I wouldn’t put together in a million years. He gets frustrated and lonely, and he both wants and disdains attention, and he asks questions about justice and fairness that make me wish I could pick him up and give him the cuddles he very clearly would not accept. I have no idea what to do about that. But in moments when my spiritual path seems impossibly hard and I ask myself where the joy in it lives, he’s the first thing that comes to mind.

Sri Krishna, as a young child with foster mother Yesoda [public domain]

It has not escaped my notice that all of this happened right when my therapist and I started to talk about self-parenting. “You are incredibly hard on your past self,” she said to me at one point. “Would you be that hard on a kid?” When I shook my head, feeling a little guilty, she went on. “There are some things that you needed, growing up, that you didn’t get. What if you gave them to yourself?”

I don’t consider pushing my niece on the swing the same as swinging on it. In the same way, I don’t think that hanging out with my step son is the same as self parenting, But I do recognize that getting to know children has given me context and grace for the kid I used to be. My memories are no longer of myself, as I am now, but small – they’re of a little stranger who deserved someone’s attention and encouragement. I can feel as protective and supportive of that kid, in their flailing attempts to figure things out, as I do of the other children in my life. I can even, sometimes, be patient with myself when I am hurting and out of my depth, or bored, or cranky.

For the first time, I’m starting to understand the benefit of getting to know kids – and I’m realizing how thoroughly they’re locked out of community. The group I used to belong to was explicitly 18+, although there was no adult content in our rituals or theology. We did not welcome children to our space, which meant that their parents were also unable to participate. While I’ve seen some events make a gesture towards welcoming kids, those are usually booths or spaces set aside from the main group and staffed by volunteers, not ways to welcome younger voices and experiences into the flow of things. Taken in tandem with scheduling and other kinds of accessibility, I can count on my fingers the number of times I’ve seen a child at a Pagan event having anything that even looked like it approached a good time.

It’s an especially stark contrast considering that all of the most powerful magic, all of the best rituals I have attended, have been about or for children. I still think about the ritual naming my friend’s child after the difficult beginning of his life, spinning the blessings of his community into health and love and support for the rest of his days. I still mourn the burial of a longed-for baby after a miscarriage, kneeling in the dark, in the dirt, as her parents and I tried to send her off with the love that she was owed. There’s no chanting circle, no portent or offering, that has ever matched the power of those moments for me. I doubt there ever will be.

I don’t consider myself a parent. But the older I get, the more the children in my life bring me joy, make me kinder and gentler towards myself. I want to give them all the things I’ve made for myself – community, and opportunity, and access to magic. I know that these are the feelings that adults have had for the kids in their lives since before we could be classified as human. It still feels groundbreaking.

Dionysus as a child riding upon a satyr. Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli. [public domain]

My brother raises meat rabbits. Helping them butcher means helping to make sure that my niece will get the bunny burger she loves all winter. My brother is, at this point, an old hand at butchering and I’m still learning, so they pause occasionally to show me the right cuts, the knife sliding between muscles so defined it reminds me of a medical textbook. By the time we’re done, we are spattered with blood, a bowl set aside full of meat ready for processing and another at our feet filled with offal and blood.

I look at the bowl of castoffs, and the little wanting pressure at the back of my head kicks up again. I sigh.

“Can I- do some weird stuff with this, before we get rid of it? I think he wants some.”

They raise an eyebrow at me, and laugh. “I mean, sure? Mine just had a period when she ate Cheerios and applesauce mashed into a paste for a week, and I have to keep convincing her not to eat raw flour. Have at it.”

“Great,” I say, frowning at the mess in the bowl. I’m just glad I don’t have to explain to a human child why this is a bad idea. I can put anything aside for an hour while we clean up. “Can I get uh – some heavy cream? And some hot sauce?”

My brother makes a noise of fond disgust, and the back of my head is filled with delight.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.