ROME – A new study may be upending long-standing beliefs about the domestication of cats, suggesting that it wasn’t agriculture or pest control that first brought felines into human homes—it was religion.

Working with international colleagues, researchers from Tor Vergata University in Rome analyzed ancient and modern DNA samples from 87 cats. Their findings, published in bioRxiv, reveal that the domestic cat (Felis catus) descends from the African wildcat (Felis lybica lybica) and did not arrive in Europe with Neolithic farmers, as was once believed. Instead, the research shows that cats were introduced to Europe from North Africa over the past 2,000 years.

The findings appear to reshape our understanding of cat domestication. While a 2001 discovery of a 9,500-year-old human-cat burial in Cyprus had led many to believe cats were domesticated on the Mediterranean island, newer studies disprove this. Researchers at the University of Exeter, using skeletal measurements, found the remains to be those of a European wildcat rather than a domestic cat. The Rome team confirmed this by analyzing nuclear DNA.

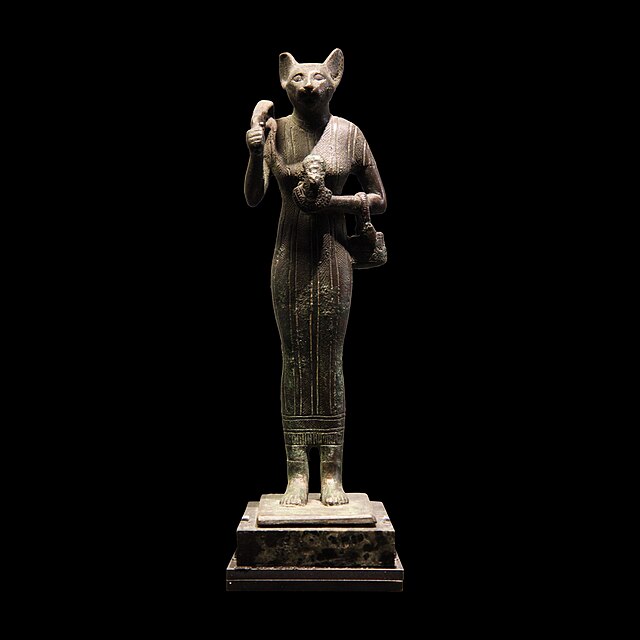

Bastet playing the sistrum. Bastet E 4252 [Photo Credit: Rama Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 France]

With Cyprus ruled out, attention turns once again to ancient Egypt—and this time, with new insights. According to the study, the push to domesticate cats may have originated not with farmers trying to reduce rodent populations, but from religious practices tied to the worship of Bastet, the feline-headed goddess of protection, pleasure, and health.

Early depictions of Bastet in Egypt show her with the head of a lioness. Over time, particularly around the first millennium BCE, her image shifted to that of a house cat. This symbolic transformation coincided with the emergence of large-scale rituals that involved the mass mummification of cats. Millions of cats, both free-roaming and specially bred, were sacrificed and offered to Bastet at temples throughout Egypt.

These temples, often located near fertile agricultural regions, provided ideal conditions for wildcats to thrive. Drawn by abundant food in grain stores and by proximity to humans, wildcats were already a familiar presence. But the rise in religious devotion to Bastet brought them into closer contact with people. Cats were raised, handled, and sometimes even bred within temple precincts, leading to a population of more docile and human-tolerant animals.

“This transformation was coincident with the rise of cat sacrifice, whereby millions of free-ranging and specifically bred cats were mummified as offerings to the goddess,” the researchers explained. “This would have provided the context for the tighter relationship between people and cats that led to the wildcat’s domestication, motivated by their newly acquired divine status.”

Over time, some of these cats left the temples and entered homes—not only as sacred animals but also as companions. What had begun as ritual practice gradually shifted into domestic familiarity. In this way, the religious reverence for cats created a cultural and environmental niche that made domestication possible.

“Our results offer a new interpretative framework for the geographic origin of domestic cats,” the authors explained, “suggesting a broader and more complex process of domestication that may have involved multiple regions and cultures in North Africa.”

The study further reveals that cats expanded out of North Africa in two waves. The first, during the early first millennium BCE, and the second, over the last two millennia, shaped the modern domestic cat population. This challenges earlier views that cats spread with the agricultural expansion from the Fertile Crescent or the Levant.

“The increasingly intensive relationship between humans and cats in the Nile Valley is demonstrated by their role in the Egyptian state cult of Bastet, and as rodent-killers in the agricultural economy,” the study noted.

Bastet, one of Egypt’s most beloved deities, was associated with protection, fertility, music, pleasure, and good health. Though originally portrayed as a lioness, she gradually took on a gentler image—a domestic cat embodying grace and nurturing. Her cult grew especially prominent during the first millennium BCE.

Temples to Bastet, especially in Bubastis in the Nile Delta, became major pilgrimage sites. Devotees offered mummified cats as tokens of devotion. Bastet was believed to guard homes from evil spirits and disease, and her association with cats helped elevate them to sacred status in Egyptian culture.

Bastet’s legacy continues today. She remains venerated in modern Pagan and Kemetic traditions.

This religious origin story challenges modern assumptions that domestication is always driven by utilitarian needs, such as pest control or farming efficiency. In this case, spiritual practice and divine association appear to have played a leading role.

One of our cats, Grigio, was informed of the findings. [Photo Credit: S. Ciotti]

While this research marks a major advance, it also underscores the need for further study. Only a handful of wildcats from North Africa and the Levant have been genetically sampled. Broader genomic analysis—particularly in Egypt—will be crucial for fully tracing the cat’s journey from predator to pet.

Still, the study offers a profound shift in understanding. The domestication of cats may have begun not in a farmhouse, but in a temple, where they were not just fed or sheltered, but revered and even worshiped.

According to the internet, little has changed.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.