VIENNA – Many traditions in modern Paganisms have a powerful focus on the hearth. The hearth holds deep symbolic and spiritual significance in many Pagan paths, often representing home, family, sustenance, and the sacred center of both domestic and communal life. In some traditions, the hearth manifests the sacredness of the home and serves as a space for honoring ancestors and maintaining devotional practices.

Unsurprisingly, scholars widely agree that fire was essential not only for human survival during the last Ice Age but also for human migration. Harnessing fire is arguably one of the most essential technologies that has enabled humans to survive and thrive across the globe. However, in Europe, archaeological evidence of hearths from the coldest period—between 26,500 and 19,000 years ago—is surprisingly scarce.

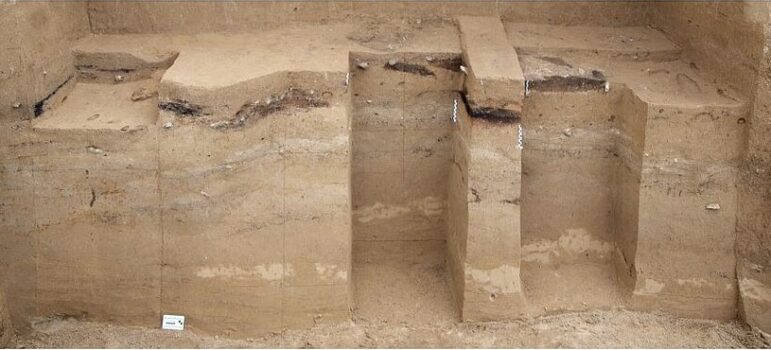

“The large fireplace 1 covered by 2.5 metres of loess sediments.” via/C: Philip R. Nigst.

A new study published earlier this month in the journal Geoarchaeology helps to somewhat close that gap by identifying sophisticated techniques our ancient ancestors used to maintain hearths. “Arguably, one of the most fundamental tools for human survival during this cold and arid period was the ability to create, maintain, and use fire,” the authors write. “While fire is widely considered a ubiquitous tool in modern human behaviour, there are surprisingly few well-described combustion features during the LGM [Last Glacial Maximum] in Europe.”

The research focuses on discoveries in Ukraine that are helping to fill in some of these missing pieces. Scientists have studied three ancient fire pits dating from the coldest part of the Ice Age. These hearths, uncovered in 2013 at a site called Korman’ 9, are between 23,000 and 21,000 years old. They offer a rare glimpse into how people survived and used fire during a time when it was most vital.

The large fireplace 1 covered by 2.5 metres of loess sediments. via/ C: Philip R. Nigst.

“Fire was not just about keeping warm; it was also essential for cooking, making tools, and for social gatherings,” says Philip R. Nigst, one of the lead authors and an archaeologist at the University of Vienna, in a statement. “We know that fire was widespread before and after this period, but there is little evidence from the height of the Ice Age,” added William Murphree, lead author of the study and a geoarchaeologist at the University of Algarve.

To study the hearths, researchers used specialized techniques such as microstratigraphic analysis (which examines soil layers in fine detail), micromorphology (the microscopic study of soil and sediment), and colorimetric analysis (a method used to detect chemical compounds).

The analysis shows that, during the peak of the Ice Age, humans primarily used wood—particularly spruce—as fuel for their fires. Charcoal remains support this, but researchers also believe that materials such as bone or animal fat might have been used. “Some of the animal bones we found were burned at temperatures above 650 degrees Celsius,” explains Marjolein D. Bosch, a zooarchaeologist affiliated with the University of Vienna, the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the Natural History Museum Vienna.

If confirmed by further research, the use of animal bones and fats as fuel would indicate an even higher level of fire-making expertise than previously assumed. “We’re now trying to determine whether they were used intentionally as fuel or were simply caught in the fire by accident,” Bosch added.

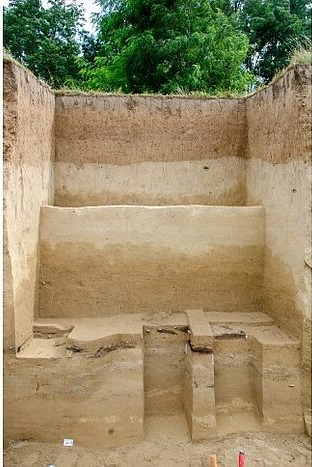

Excavation site Korman’ 9 located at the shore of the Dnister River in Ukraine. via/ C: Philip R. Nigst.

The three hearths discovered are all open and flat, yet the evidence points to a sophisticated understanding of fire. The ways the hearths were constructed and used seem to have varied by season. One hearth, for example, is larger and thicker than the others, suggesting it was built to produce higher temperatures. “These people had excellent fire control and knew how to adjust their use of it depending on their needs,” says archaeologist Katerina Harvati.

Analysis revealed that the fires reached temperatures exceeding 1,112 degrees Fahrenheit (600 degrees Celsius), indicating a strong understanding of fire-building techniques among Ice Age hunter-gatherers. Higher temperatures mean more efficient burning, suggesting these early humans knew how to manage fire with precision. Although all three hearths were similarly shaped, researchers believe they were adapted for seasonal use. The larger hearth likely produced the hottest flames.

“People had excellent control over fire and adapted how they used it depending on their needs,” said Nigst. “Our findings also show that these hunter-gatherers returned to the same site at different times of the year during their seasonal migrations.”

While the study did not directly address whether the site held ritual significance, Nigst emphasized that “our research also suggests that these hunter-gatherers returned to the same site at different times of the year as part of their seasonal migrations.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.