Uncovering the Past

STUTTGART, Germany – Roughly 2,500 years ago, during the late Hallstatt period, a male Celtic warrior endured a serious injury when an arrow or similar projectile pierced the left side of his pelvis. According to new research, the man not only survived the attack but also received medical treatment so advanced for its time that his wound eventually healed. The rare and revealing discovery offers new insights into the sophisticated healthcare practices of Iron Age Europe.

The study, published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, focuses on the man’s remains buried beneath a large mound at Heuneburg, a prehistoric hillfort located in present-day southern Germany. The site was a major center of power during the early Iron Age and has long been known for its rich archaeological finds.

But this particular burial adds a new layer of insight—not just into ancient warfare, but into ancient medicine, and especially how people of high status were cared for in the aftermath of battle.

Archaeologists first unearthed the skeleton decades ago. It was buried beneath a mound approximately 140 feet (43 meters) wide and nearly 10 feet (3 meters) high. Despite the grave being looted in antiquity, the burial still contained valuable clues, including fragments of a chariot, pieces of a metal belt, and decorative jewelry. These artifacts helped experts date the burial to between 530 and 520 BCE, during a time known as the late Hallstatt period, part of the larger European Iron Age.

The man buried there was estimated to have been between 30 and 50 years old when he died. His skeleton showed clear signs of trauma to the left ischial bone—a thick bone at the base of the pelvis that supports body weight when sitting. This injury, researchers concluded, was caused by an arrowhead, likely during a combat situation.

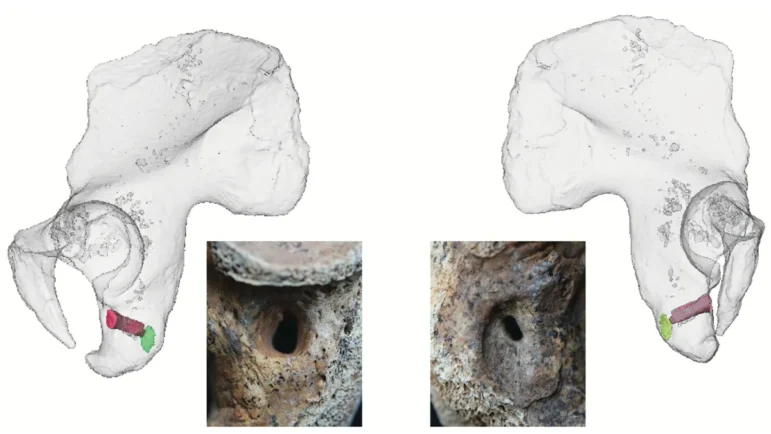

Using modern medical imaging techniques—specifically, computer-based CT scanning—the researchers created a three-dimensional model of the bone injury. This allowed them to closely study the shape, size, and direction of the wound. The arrow had entered from the front-left side of the man’s body, suggesting he was likely shot while running, seated, or possibly riding on horseback or in a chariot.

What makes the discovery especially significant is the condition of the wound. The arrow had penetrated deep into the pelvis but had not completely passed through the bone. The edges of the injury were smooth and showed clear signs of healing. This suggests not only that the arrow was removed, but that the wound was cleaned and treated, and the man lived for several weeks—or even months—after the injury.

Left Pelvic bone of a Celtic warrior injured with an arrow. (Image credit: C. Röding and H. Rathmann / Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen)

“This kind of healing implies deliberate and careful medical attention,” said Michael Francken, the study’s lead author and an osteologist State Office for the Preservation of Monuments at the Regierungspräsidium in Stuttgart, Konstanz, Germany. “The arrowhead would have had to be removed, and the wound likely enlarged in a controlled way to make that possible.”

While no written medical texts survive from this period, the evidence suggests that Iron Age healers possessed specialized tools and techniques. This is particularly notable, considering how little is known about medicine in prehistoric Europe. The fact that the injury was managed successfully indicates a surprising level of anatomical knowledge and practical surgical skill, at least for members of the elite class.

Indeed, the man’s social status likely played a key role in his survival. In Iron Age societies, those with wealth or political power often had access to better food, housing, and, apparently, healthcare. The study notes that a common person likely would not have received the same level of care or been given the time to recover. “This suggests the injured person probably belonged to a social class exempt from daily physical labor for sustenance,” the researchers wrote.

The nature of the conflict that led to the injury remains a mystery, but it was unlikely to have been a hunting accident, according to the researchers.

Although the exact cause of death is unknown, Francken said the healed state of the bone indicates that the man lived with the injury for some time before dying. “Unfortunately, I can’t say whether there is a connection between the individual’s death and the injury,” he explained. “But what we can say is that he received careful treatment and lived for quite a while afterward.”

View from the Heuneburg over the Danube to Bussen” Image Credit: Dionysos1970 CCA-SA 4.0]

Furthermore, the early Celts did not leave behind written records of their battles, and no specific evidence has been found at the site to indicate the circumstances of this particular fight. However, Heuneburg was a fortified settlement with clear signs of political and military significance, so combat injuries would not have been uncommon, especially among elites involved in warfare.

What is clear is that this individual was honored in death. His burial beneath a massive mound, surrounded by remnants of a chariot and finely made ornaments, reflects a “princely” status. His bones, now studied with 21st-century tools, offer a rare glimpse into how ancient societies cared for their wounded—and how even in a time without hospitals or antibiotics, survival from life-threatening injuries was possible for the few who had power and privilege.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.