Düsseldorf, Germany – On Nov.6, archaeologists from the Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe (LWL) issued a statement. They had discovered two temples in the remains of a Roman military camp in Haltern in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. These structures dated to the reign of the Roman Emperor Agustus 27 B.C.E. to 14 C.E. Between the temples, archaeologists found a burning pit, like ones used for sacrifices.

Archaeologists from the LWL reported that only clay fragments remain. Those clay fragments strongly resembled the remains of the typical “large podium temples made of stone.” A podium temple has a raised pedestal or base. Unlike most podium temples, the Haltern temples were made of wood. During the reign of Augustus, similar podium temples were common. Until this discovery, that style of temple and sacrificial pit had not been found in Roman military camps.

The building floor plans formerly belonged to rectangular cult buildings made of clay framework. In front of them was a small portico made of two columns. LWL/C. Hentzelt

The western temple had the shape of a square, with sides measuring 30 meters (98.4 ft.). Its entryway had a width of five meters (16.4 ft.). On each side of that entryway, stood a wooden column. The two temples did not exist in isolation. Roman Haltern had a military complex of 2,000 square meters (21527.8 square ft.). Those temples were in that complex.

In the excavation area in the Haltern main camp, the foundations of the cult buildings can still be seen as faint soil discoloration. The picture shows the cross section through a post trench and a post track. LWL/C. Hentzelt

Both temples have a similar appearance. Between them, lay the remains of a sacrificial pit. A small niche surrounded that pit. Unfortunately, the soil in this area had been greatly disturbed. That disturbance has prevented archaeologists from recovering sacrificial remains in that pit.

Archaeologists first excavated this site in 1928. At that time, they interpreted the temples as part of an administrative complex of the military camp. Later, those archaeologists abandoned the site. A recent survey revealed a measurement error. When corrected, the design of the two structures matched the design of the podium temples.

The sacrificial pit resembled the design of the nearby burial ground. Roman custom and law, however, prohibited human burial within a settlement area.

Though there is scholarly debate on the issue, ancient Romans frequently made offerings and may have understood them quite differently than how they are understood by contemporary societies.

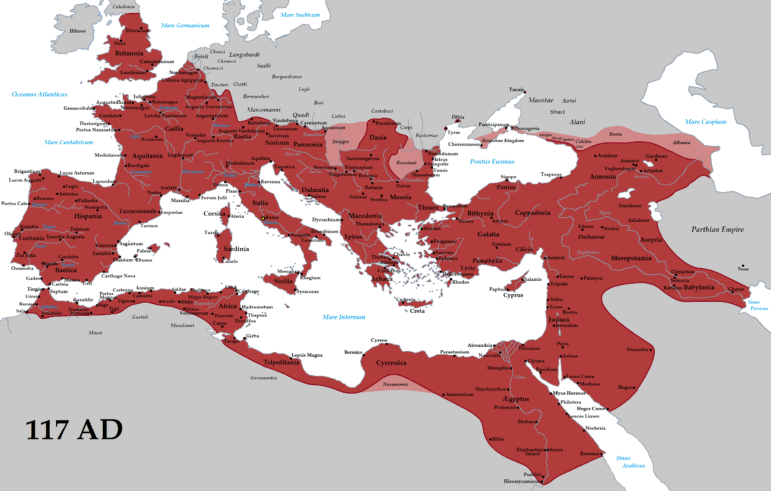

Roman Empire at its full extent in 117 CE under Emperor Trajan. [Image Credit: Tataryn – CC BY-SA 3.0

Celia Schultz wrote about ancient Roman sacrifice in “Romans and Ritual Murder,” and in “Roman Sacrifice Inside and Out.” Leonhard Schmitz wrote about Roman sacrifice in Sacrificium. Schultz argued that the Romans used human sacrifice to distinguish Roman culture from “primitive” cultures. Those “primitive” cultures tended to be ones that the Romans had conquered. The Romans did kill people in what looks like a ritualistic manner. They just did not label it a “sacrificium,” the Roman word for sacrifice.

It raises the question as to why the Romans made offerings. Schmitz reported that ancient Romans engaged in sacrifices for many reasons. Some Romans made offerings to show gratitude to a god. Other Romans made sacrifices to lessen a god’s anger. Some Romans made sacrifices to gain a specific favor from a god. Others made sacrifices for non-specific divine goodwill. He divided sacrifices into two broad major categories: unbloody and bloody sacrifices; a division that is seen today in modern spiritual practices that developed independently of Roman influence.

![]()

We really hate to keep asking.

We are grateful to our readers for your support, however it manifests. Right now, we need readers who can help fund Pagan journalism to help us continue serving the community. This is how to help:

Tax Deductible Donation | PayPal Donations | Join our Patreon

We remain one of the most widely-read news magazines within modern Paganism, and our reporters and columnists remain dedicated to a vision of journalism for and about our family of faiths.

You can also help us by sharing this message on your social media.

As always, thank you for your support of The Wild Hunt!

![]()

In unbloody sacrifices, Romans would offer fruits, cakes, and liquids to the gods. Cakes could have the shape of an animal. Romans could substitute an animal-shaped cake for the actual animal. Roman elites would generally sacrifice the animal. Less wealthy citizens could sacrifice the substitute. Other unbloody sacrifices would involve libations and the burning of incense. The Romans would frequently combine libations and burning incense with other rituals.

Bloody sacrifices involved the ritual killing of a living animal. The Romans called the sacrificial animal “hostia” or “victima.” Schultz distinguished between the Roman and modern understanding of a sacrificium. For the ancient Romans, the key moment may have been the anointment of the victim.

The sacrificium did not consist of a single act, but rather a series of inter-related actions. Each step of the sacrificium is built on its prior steps. The word “sacrificium” evolved from the phrase “sacrum facere” (to make sacred). Sacrifice makes something sacred. The process would bring the victim from the mundane world into the sacred world. It would also bring the celebrants and the “congregation” from the mundane to the divine and back to the mundane. Like modern communion, the meal that ended the ritual would allow celebrants to partake of the divine.

A sacrificium consisted of the following interrelated actions. First, the celebrants processed to the site of the sacrificium. Next, they made a preliminary offering of prayers, wine, and incense, a “praefatio.” At the center of the ritual, would be the “immolatio.” It had three sub-stages. A priest would first anoint the victim with mola salsa (a mixture of spelt wheat and salt). A priest would then run the flat edge of a knife along the victim’s back and cut a few hairs from its back. The immolatio would end with the priest killing the victim. After that, priests would inspect the animal’s entrails, a “litatio.” Finally, the celebrants and the audience would hold a communal feast.

Schultz argued that the two key stages of the sacrificium were the anointing and the communal meal. Its death would move the victim from the mundane to the sacred. It had already been made sacred.

The Latin word “immolatio” evolved from an Indo-European root “*melh” (to crush, or grind). Both the English word “mill” and the Latin term, mola salsa, a sacred cake made by the Vestal Virgins in ancient Rome, derive from this same root. Schultz argued that this suggests the importance of the anointment in the sacrificium. The anointing may have been “either the single, critical moment or an especially important moment in a process that transferred the animal to the divine realm, is that mola salsa seems to be the only major element of sacrifice that is not documented explicitly by a Roman source as appearing in any other ritual or any other area of daily life: processions, libations, prayers, slaughter, and dining all occurred in non-sacrificial contexts.”

In earlier times, Romans would burn the whole animal on the altar. Later, the Romans would place the fat-covered legs on the altar. They would then burn it on the altar. Like an offering of incense, the gods would consume the smoke rising from the burning flesh. The gods did not eat the flesh. The human audience and celebrants would then engage in a communal meal of the cooked, sacrificial flesh.

More succinctly, the Romans may have understood a bloody sacrifice as an animal’s ritual consecration. Afterward, they would have eaten the offering. The types of animals sacrificed matched those that the Romans ate. This congruence may show the importance of the communal meal to the ritual where the mundane and divine came together.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.