TWH – A dog named Mutton that crossed into spirit in 1859 has shared some secrets about the history of dogs in North America. Through Mutton’s pelt, researchers were also able to tell stories of the oppression of First Nation and Native American culture in the Pacific Northwest.

Dogs have been present in the Americas for over 15,000 years, having been domesticated in Eurasia before accompanying the first people to reach North America. Dogs hold significant cultural importance in Native American societies, playing various roles that extend beyond mere companionship. More than merely for companionship, husbandry, and assisting with transportation, many Native Americans and First Nations attribute spiritual and symbolic significance to dogs. Some view dogs as spiritual guides or messengers and their presence is often linked to spiritual ceremonies and rituals. In some Indigenous cultures, Dogs are revered for their connection to nature and have been sometimes involved in medicinal practices and healing ceremonies.

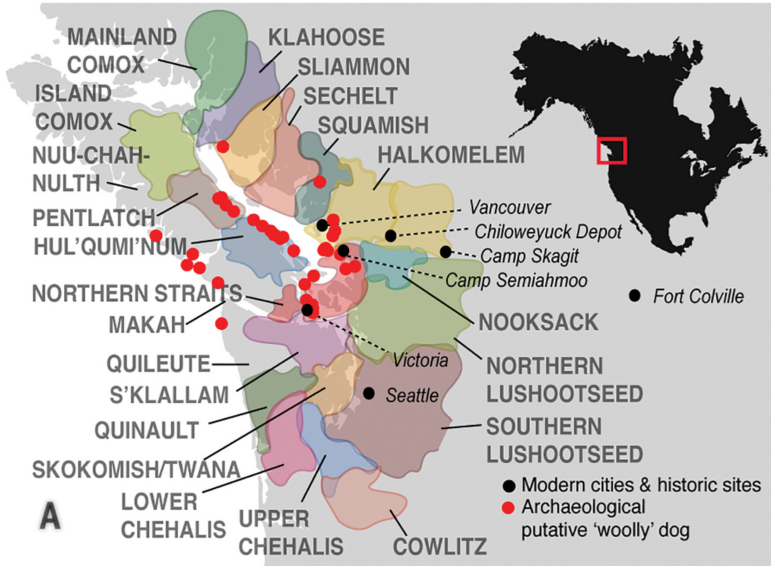

Archaeologists have found remains of dogs dating back around 5,000 years in the coastal regions of present-day Washington state and southwestern British Columbia. But one particular type of canine has been of interest.

Forensic reconstruction of a woolly dog based on Mutton’s pelt measurements and archaeological remains [via Science | AAAS

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Indigenous Coast Salish peoples in the Pacific Northwest maintained a specific breed of long-haired dogs for harvesting their hair or wool, which was used for textile fibers. Alongside alpacas and llamas, these woolly dogs were among the few animals intentionally bred for their fleece throughout the Americas.

However, the practice of keeping woolly dogs and weaving textiles from their yarn declined in the 19th century, and by the early 20th century, the dogs were considered extinct. The decline of the woolly dog has been “attributed to the proliferation of machine-made blankets by British and American trading companies in the early 19th century.” However, the researchers noted that this doesn’t explain the whole story. They noted that the dog’s wool had tremendous cultural importance having been used in high-status items and regalia. They were also reared and owned by high-status individuals. So, what happened to woolly do and if the breed was Indigenous, has remained unknown.

Mutton is sharing some clues and helping to solve the mystery.

![]()

We hate to keep asking, but this is how to help The Wild Hunt.

We are grateful to our readers for your support however it manifests. Right now, we need readers who can help fund Pagan journalism to help us continue serving the community. This coverage of this story you only see here: Only TWH publishes science news from a Pagan perspective.

This is how to help:

Tax Deductible Donation | PayPal Donations | Join our Patreon

We remain one of the most widely-read news magazines within modern Paganism, and our reporters and columnists remain dedicated to a vision of journalism for and about our family of faiths.

You can also help us by sharing this message on your social media.

As always, thank you for your support of The Wild Hunt!

![]()

“When I saw Mutton in person for the first time, I was just overcome with excitement,” said evolutionary molecular biologist Audrey Lin, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the American Museum of Natural History and lead author of the study. “I had heard from some other people that he was a bit scraggly, but I thought he was gorgeous.”

Coast Salish artisans employed the wool from these dogs to create blankets and various woven articles with diverse ceremonial and spiritual applications. Woolly dogs carried spiritual importance and were frequently regarded as cherished members of the family. Serving as symbols within numerous Coast Salish communities, these woolly dogs adorned woven baskets and other artistic expressions.

Naturalist and ethnographer George Gibbs reported caring for a woolly dog and when that dog died, he preserved the pelt and sent it to the Smithsonian. That pelt belonged to Mutton.

A team of researchers led by the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC took a close look at Mutton’s pelt and performed genetic analyses. But the team of researchers also included co-authors who were Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and Master Weavers, who provided crucial context about the role woolly dogs played in Coast Salish society.

“Coast Salish traditional perspective was the entire context for understanding the study’s findings,” Anthropologist Logan Kistler one of the study’s authors.

“We were very excited to participate in a study that embraces the most sophisticated Western science with the most established Traditional Knowledge,” said Michael Pavel, an Elder from the Skokomish/Twana Coast Salish community in Washington, who remembers hearing about woolly dogs early in his childhood. “It was incredibly rewarding to contribute to this effort to embrace and celebrate our understanding of the woolly dog.”

So what did Mutton reveal? First, 85% of Mutton’s ancestry can be linked to pre-colonial dogs.

The unexpected nature of this ancient lineage is noteworthy, given that Mutton existed many years following the introduction of European dog breeds. This suggests a high probability that Coast Salish communities preserved the distinctive genetic characteristics of woolly dogs until shortly before their extinction.

Second, the team found 11,000 different genes through Mutton’s genome that created the desirable, fluffy characteristics of the breed’s woll fibers. They also found 28 specific genes that accounted for the hair growth and curly characteristics. These genes are similar to their human counterparts and might also have been activated in other species like the ancient woolly mammoth.

Coast Salish ancestral lands include the inner coastal waterways of the Salish Sea in southwest British Columbia and Washington State. Archaeological woolly dog data are from. Distribution of the Coast Salish languages in the 19th century are as indicated by colored areas [via Science | AAAS

Unfortunately, the genes couldn’t shed light on why the dog declined. But the Coast Salish Elders could and picked up the story from there. Indian Agents were individuals appointed by the government, often in the context of colonial or settler societies, to manage and oversee relations with Indigenous peoples. These agents served as intermediaries between the government and Native American or First Nations communities.

Along with priests and police, Indian Agents forced Indigenous communities to get rid of their dogs. “The dogs represented high status and traditional practices that threatened British and later Canadian dominion and as such were removed through policies of assimilation, “ the team wrote in their article.

Stó꞉lō Elder Rena Point Bolton, who was 95 years old in 2022, recalled how Th’etsimiya, her great-grandmother, kept woolly dogs, “Our people were not allowed to spin on shxwqáqelets [traditional spindle whorls]. They could spin on a European one but not on the shxwqáqelets.”

Elder Bolton added “They couldn’t use their looms, and they would take them out and burn them or they would give them to museums or collectors … The generation that was there when the Europeans came and colonized us, that’s where it ended, and there [were] just a few people who went underground. And my grandmother and my mother were two of them.”

Artist Eliot Kwulasultun White-Hill (Snuneymuxw) said (9): “It starts to unravel, in a way, people’s understanding of us as a hunter gatherer society … Our relationship with the woolly dogs, our relationship with the camas patches and the clam beds, the way that we tended the land and tended the forests … these all show the systems in place that are far more complex than what people take for granted about Coast Salish culture.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.