I told the first of the tales in college. The capstone for my creative writing major, it came out instinctively, half-considered and in an accent I could only call “country,” an accent that tasted like my father’s people around the kitchen table.

I stood up at a podium and told all those who’d gathered about a man at the end of a long life of adventure, unrepentant and amused as he ambled toward his just reward. I’d known him for years, by that point, and feeling him in my tone of voice and the cant of my body towards the audience was familiar and welcome, like introducing an old friend.

Afterwards, folks would come to me and say how much they’d enjoyed it, and I took the compliments as well as I could – but I couldn’t shake the feeling of surprise. I didn’t think the story was anything special, or deserving of all this praise – or certainly not praise for me.

It was just Jack.

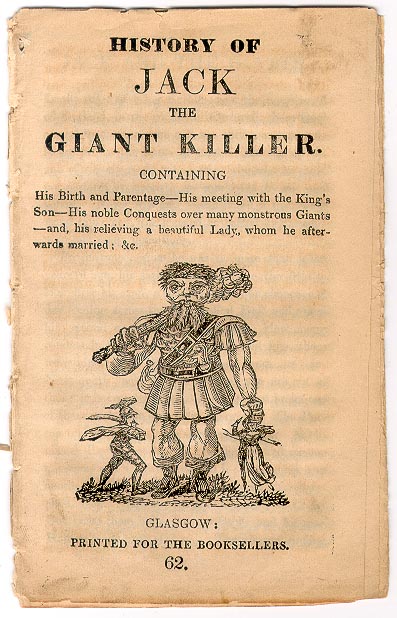

Title page to a chapbook of Jack the Giant Killer, c. 19th century [public domain]

Now, everyone knows a Jack tale. There’s the one about the beanstalk, sure, and most have heard a story or two about him in one of his many run-ins with the devil. He shows up in Appalachia, in Germany, in the deep south – although there he’s just as likely to be called John – and in enough forms of media and song that it’s just about impossible to get through life without knowing him somehow.

The details change, but the man is the same – clever, quick, and set on tearing down whatever rich good-for-nothing has put himself above all the decent and hard-working folk in these parts. And if that leaves Jack the better for it, a little richer, a little better fed, well – that’s only right, isn’t it? In most forms he is a spirit of the people, an embodiment of the everyman – maybe not too smart but laughing and fearless and willing to get his hands dirty.

It’s impossible to say when I met him first, but I took up with him in college – first as a research topic, then as a character in a weekly tabletop role-playing game, and finally as what might as well have been an organizing theme in my life.

This was before I had found myself, before I was ready to claim my own name and walk my own particular path, but through the stories I told about Jack, that work suddenly got a lot easier. I talked about his family, his identity, the great loves that pushed him through great trials – my own inventions, adding onto a history of people telling stories that went back hundreds of years. We told stories together, riffing on older versions, tangling up threads until I realized that half the time I was talking about myself.

I was telling a Jack story when I realized I was trans. I was telling a Jack story when I realized I was in love.

In the moments when I doubted myself I reasoned that even if I were writing a shallow character, well, at least I was having fun. More than that, I was figuring things out, becoming a better writer and a better version of myself. Wasn’t that the point of writing?

In the moments when I had no doubt, I loved him as an author loves their dearest creations, the parts that are most themselves. I planted myself in him and, with a trellis made of a thousand stories, grew toward the sky.

A traditional Irish turnip Jack-o’-lantern from the early 20th century. Photographed at the Museum of Country Life, Ireland. [Rannpháirtí anaithnid, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

This time of year, the story that suggests itself for telling is the one about the lantern.

The way I heard it, when Jack was an old man and past the time of his most wild and rambunctious shenanigans, he took it into his head to die. Now, part of that was simple, but when a soul has been around as long and gone as far as Jack had, well, that last leg of the journey tends to be complicated. Finding that nobody was going to come and get him off the front porch where he’d breathed his last, Jack stood up out of his rocker, shouldered his bag, and started the long trek up to heaven.

“Now, you know well enough that you’re not welcome here, all the wickedness you’ve done,” St. Peter said from well up in the Pearly Gates (where he was pretty sure Jack couldn’t get to him.) “Go on now. Only one place for you. Git!”

“Awful cold out there,” Jack pointed out. “Thought you lot was pretty keen on charity.”

There was some hemming and hawing, and then down from the sky floated a candle, not lit yet, from the great chandeliers that hung in one of the mansions right over that first hilltop.

So Jack, never one to overstay his welcome, picked it up, turned on his heel, and started an even longer walk back the way he’d come, past his own comfortable rocker and the old dog in the yard, out to where another set of gates waited. These, usually wide open, slammed shut as soon as he came into view.

Like I’d mentioned, Jack had some run-ins with the devil back in the day. Tricked him out of a few souls, an instrument or two, that sort of thing. So even though he came right up to the gates and knocked, there wasn’t a single sign that they were going to open up for him now.

“Now,” he said, looking up. “Now, I’ve got to go somewhere. It’s my right to come in – they turned me away from the other place.”

All he got was a voice on the other side of the door saying, “Tough luck!” which Jack did not think was a very gentlemanly thing to say at all.

By this time it was getting dark, and any walk from there was going to be a long walk indeed, and Jack was formulating an idea. “Can you at least give me something to see my way by?” he said. “I’ll let myself out.”

There was a brief and hideous muttering on the other side of the gate, and then a piece of coal from the ever-burning lakes came sailing out to land at Jack’s boot. “Much obliged,” he said, and picked it up as well as he could, and high-tailed it back to the land of the living.

Now, he didn’t quite belong there anymore, and that coal was hot as anything in his hands, so Jack dumped it in the first place he thought might be able to hold it – which was right in the center of a turnip patch. (Some might argue it was a pumpkin patch, and they’d be right in their own way.) He looked at it a moment, and then he bent down and harvested himself a turnip, and cut a hole for the candle to go in, and some more for the look of the thing, and made himself a lantern that he lit with that same coal. Then he walked back to his home, with his front porch and his dog – because Jack never did see the point of going places he wasn’t wanted.

It caused quite a commotion at first, having him back, and the story spread as stories about him always did, and well – it was customary, even then, to light a candle and guide the souls of the dead back home for a visit, once a year. Might be that folks got a little confused in the storytelling, or maybe it was just the spirit of the thing – but those little lanterns of Jack’s started popping up on other porches, which Jack thought was about the funniest thing he’d ever seen. And when he took to wandering again, he carried that lamp with him, rambling through woods and bogs and all sorts of places, finding his own way through the world and the people there who’d never turned him away.

Might be that a few of those times people followed him in where they shouldn’t have gone. Might be that eventually people started lighting those candles to keep the dead away, rather than welcome them home. But those are other stories, and this is the one I’m telling.

A jack o’lantern [Benjamin Balazs, Wikimedia Commons, public domain]

Every year, I go to the grocery store and find the biggest turnip, the tidiest pumpkin that they have on offer. I carve them faces, and light them from the candle that always sits on my altar, and I think about all of the ways we find our paths, and our ways forward. I think about the places that welcome us, the people who are waiting with front porches ablaze with light. I walk into the darkest part of the year, and I am more than grateful that Jack walked this way first.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.