As the summer season enters full swing, with fall soon to follow, many individuals head for hikes or outdoor events such as Pagan festivals. Scientists and conservationists would like for us to be mindful of a central backcountry outdoor ethic: “leave no trace.”

The principle is simple: As we visit nature, we should leave everything as it was and leave everything behind.

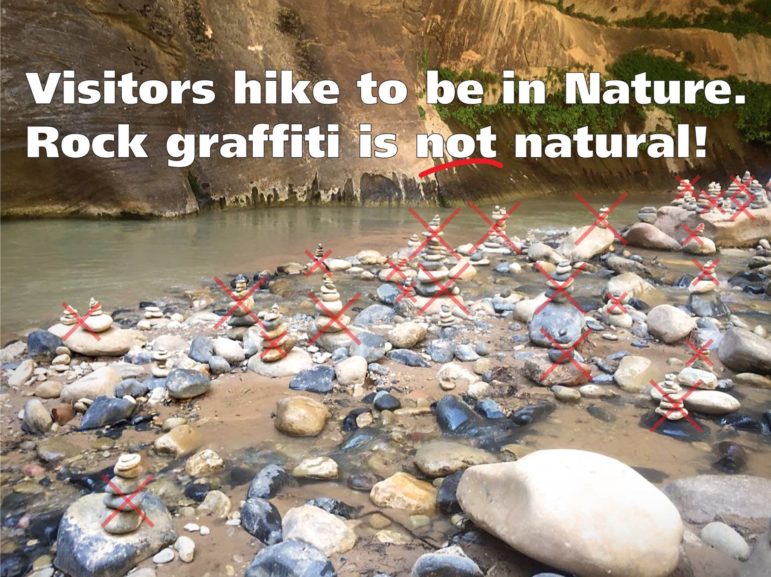

Unfortunately, one seemingly innocuous activity has grown popular over the past decade and has begun to take an ecological toll. The practice of cairn building, or rock stacking, is affecting the habitats of some endangered species, and researchers warn that there is a real consequence to the behavior that is sometimes referred to as “rock graffiti.”

Stacked stones on the beach. [Photo Credit DeFacto (CC BY-SA 4.0)]

Stacking rocks is an ancient practice, familiar to many Pagans. The word “cairn” comes from Scottish Gaelic, referring to purposefully stacked stones that were typically a marker for a burial mound. An old Scottish Gaelic proverb is cuiridh mi clach air do chàrn, “I’ll put a stone on your stone.”

Cairns have been documented on every continent humans have inhabited. The rock stacks have many purposes, from good luck to place markers to ancestor veneration. The Indigenous peoples of the Americas have used rock stacks as both burial sites and trail markers. Earthworks across Eurasia have stacked stones from thousands of years ago. Cairns are even mentioned in the Book of Genesis.

In the United States in 1896, however, the spirituality associated with cairn building was uncoupled with their practical use as trail markers. Waldron Bates created a specific style of hiking cairn in Acadia National Park. His cairns followed a specific pattern: a smaller stone pointing to the trail atop a rectangular stone balanced on two small stacks of stones. They became known as Bates cairns, and were used to ensure hikers knew they were on the right trail, preventing them from getting lost. Navigational rock cairns are now found elsewhere, like in Zion National Park and Bandelier National Monument.

The practical purpose of cairns, however, has now evolved into photography, land art, and rock-stacking competitions. Social media has made the practice popular. Today, the European Stone Stacking Championships, sponsored by the European Land Arts Festival and Stone Stacking Competition (ELAF), enters its final day at Eye Cave Beach, Dunbar, U.K. The winner will qualify for the world rock stacking championships at Llano Earth Art Festival in Texas.

ELAF and other enthusiasts of stone stacking claim that stone stacking has multiple benefits, such as teaching physics, promoting concentration and patience, and relaxation, as well as enhancing mindfulness and creativity. One person implied it benefits people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity conditions.

Announcement via ELAF 2022

The results can be extraordinary, artistic, and even mystical.

That said, stone stacking using natural material from the seaside or rivers, or simply acquiring any stone found in nature, means dislodging those rocks from the natural ecosystem. What seems like an innocent pastime can have a devastating effect on the flora and fauna of an area.

“Rock stacking can be detrimental to the sensitive ecosystems of rivers and streams,” the website of the Ausable River Association explains. “Moving rocks from the river displaces important ecosystem structure for fish and aquatic invertebrates. Many [fish] species lay eggs in crevices between rocks, and moving them can result in altered flows, which could wash away the eggs or expose the fry to predators.

“Salamanders and crayfish also make their homes under rocks,” they add, “and rock moving can destroy their homes, and even lead to direct mortality of these creatures.”

Badger Run Wildlife Rehab in Klamath Falls Oregon warned on their Facebook site that one large salamander species, affectionately known as “snot otter” and “lasagna lizard,” is being affected by rock stacking. “Moving/stacking of a stream’s stones to make rock cairns and small rock dams has now been documented to cause mortality of both larval, juvenile, & adult hellbenders,” they wrote.

Eastern Hellbenders (cryptobranchus alleganiensis) are found in the Appalachian Mountains and their populations have been on a rapid decline from habitat loss, removal of tree cover, pollution, and cairn building. Increasing human use of rivers in the Pisgah National Forest and Great Smoky Mountains National Park is accompanied by human rock stacking. Moving the rocks damages the hellbender’s food sources like crayfish and also their breeding sites. Sometimes, moving the rocks outright kills the salamanders, or crushes them when the cairn is built.

Image by Zion National Park via Facebook

Indeed, research published a few years ago noted that “anthropogenic habitat distrubance (i.e. moving and stacking rocks to build small dams)” was a significant contributor to salamander mortality.

The U.S. Forest Service has put up signs that read: Don’t Move the Rocks! Moving the rocks will destroy the homes of many important fish, insects and salamanders. Unfortunately, they have done little to prevent the practice.

Moreover, even if rocks are only temporarily moved and then put back, the damage has already been done. Pisgah River Rangers, via their Facebook account in August, wrote, “Rocks in and around rivers are important habitats for salamanders, macroinvertebrates, fish and more! In addition, when you move these rocks, you can change the flow of a stream and increase sedimentation, which may change what can survive there. This summer, we took apart more than 300 rock structures!”

The National Park Service asks that navigational cairns not be tampered with and, perhaps more importantly, asks that visitors not build unauthorized cairns. “Moving rocks disturbs the soil and makes the area more prone to erosion,” the service says. “Disturbing rocks also disturbs fragile vegetation and micro ecosystems.”

Stacking stones can also be disrespectful to those cultures that employ the practice as a form of veneration, especially when done on their current or ancestral land. The practice can also undermine the experiences of others who come to visit the area.

A few years ago, angry residents on the Isle of Skye launched a rebellion against stone stacking tourists, saying the Fairy Glen near Uig had been robbed of its natural beauty because of the practice. They cleaned up all the cairns and put up signs asking tourists to stop the behavior.

Zion National Park made the clearest appeal. “Leaving your mark, whether carving your initials in a tree trunk, scratching a name on a rock, or stacking up stones is simply vandalism.”

The National Park Service reminds us of the 7 principles of Leave No Trace:

1. Plan ahead and prepare

2. Travel and camp on durable surfaces

3. Dispose of waste properly

4. Leave what you find

5. Minimize campfire impacts

6. Respect wildlife

7. Be considerate of other visitors

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.