The Wild Hunt. The journal Antiquity reported on the material remains left as the ice melted, on a high mountain pass in Lendbreen, Norway. In the Medieval period, this site played a critical role in trade, travel, and the movement of cattle to summer pastures.

Mountain passes link one side of a mountain with another. As such, they form liminal spaces of transformation.

Lendbreen had several functions. From the Bronze Age to the Roman Iron Age, ancient people mainly hunted there. Few remains from that period survived. From the Roman Iron Age until the Middle Ages ended, Lendbreen became a trade and travel hub. In the summer, people used it to move cattle to upland pastures. Hunting continued to occur sporadically. Unlike other mountain passes, people used it when snow and ice-covered it. Use peaked around 1000 C.E.

The physical site

The mountain pass, Lendbreen, rises to 1920 meters (6,299.2 feet) above sea level. A series of cairns mark the pathway up to pass and down from it. Near the top of the ice patch, stands a stone shelter. None of the other mountain passes on that ridge has cairns or a stone shelter. These differences may signify a special status for Lendbreen.

Lendbreen is an ice patch, not a glacier. The material in glaciers moves with the glaciers. The material in ice patches tend to be more stationary. Lendbreen marks the first known ancient mountain pass that crosses an ice patch. The terrain of Lendbreen could be quite rough. A thick snow cover would have made it easier to cross those rough patches.

Material remains found

This area in central Norway has yielded the largest number of finds from mountain ice. Archaeologists have found 3,000 artifacts. Those artifacts include horse bones, horse dung, reindeer antlers, textiles, and tools. Bronze Age (1750-500 B.C.E) skis and arrows comprise the oldest artifacts.

The Guardian reported that in 2011, archaeologists found an intact tunic. Someone had woven the tunic from sheep wool between 230 and 390 C.E. It had a diamond twill design. Well worn, it showed repair marks. The weaver made this tunic for a slender person about 1.7 meters (5.5 feet) tall. Both the weaver and the wearer would have been pagan.

Archaeologists have found items related to hunting at the site. These items include five arrows, a “scarer stick,” and two cut reindeer antlers.

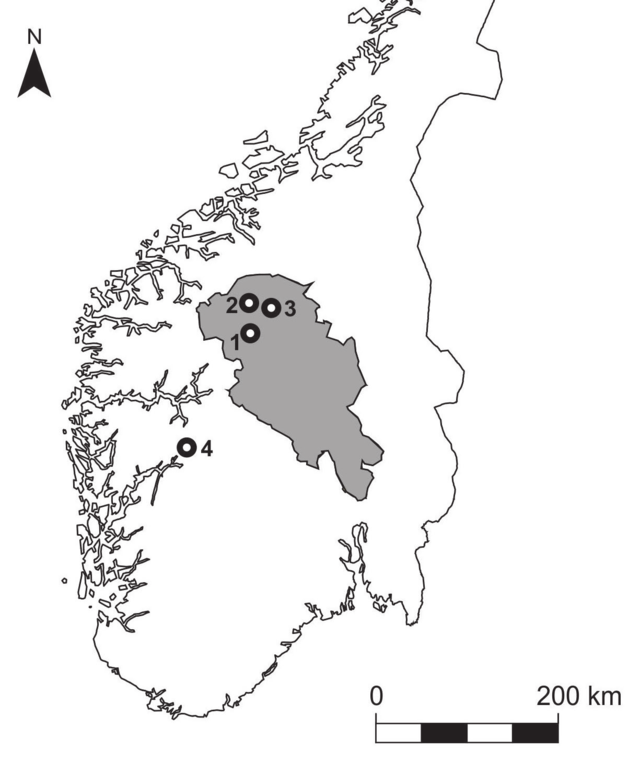

Prehistoric and Medieval Skis from Glaciers and Ice Patches in Norway Fig 1 Map of archaeological ski finds in Norway. Map of Southern Norway with Oppland County marked in grey. Find spots for main ski finds from glacial ice. 1. Lendbreen; 2. Digervarden; 3. Dalfonn [Credit: Lars Pilø, Oppland County Council, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0]

Mountain Pastures

Mountain passes function not only as nodes of travel and trade. They link the lowlands with upland mountain pastures. In the summer, herders across the globe move cattle from the lowlands to upland pastures.

In June, people would bring their cattle over the Lendbreen. From there, they would bring to the nearby mountains pastures. In September, they would make that journey in reverse.

The timing of those journeys suggests a possible linkage. The dates of that travel would roughly coincide with the summer solstice and the fall equinox. A modern Pagan could easily imagine that journey itself as a ritual. Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing if that were the case.

In the uplands, ancient people may have grown and harvested fodder. They would then bring back that fodder to the lowlands for winter feed. Archaeologists found several objects that look like a common tool of the recent past. Farmers used that tool to secure fodder on a wagon or sled. Archaeologists have dated one of these found objects to 264 to 533 C.E.

Summer farming and butter production took place in these upland pastures. Medieval Norway exported butter, reindeer antlers, and reindeer belts. People made combs out of the antlers. More than subsistence farming was going on here. Lendbreen formed part of the maritime Viking export economy.

Home-based butter production in the upland pastures raises an interesting point. Traditionally, women churned butter. Traditionally, males led cattle on journeys. Either males churned butter, or females took part in those journeys, or maybe both.

Trade and travel nodes and Lendbreen use

Lendbreen linked northern, western, and eastern Norway for trade and travel. Local oral histories reported that people would travel to western Norway. They went there to obtain barley and dried fish in times of poor harvest. Lendbreen pass may have facilitated inter-regional and long-range communication.

Material finds peaked around 1000 C.E. The use of the pass declined after that time. Archaeologists have found few items from later than 1400 to 1599 C.E.

Those years around 1000 C.E. mark the high point of the Viking Age. At that time, Viking trade had expanded around the Baltic, Irish, and North, Seas. Political power in Scandinavia became more centralized. After that, the Norse expansion ended. That end of expansion probably contributed to the gradual decline in the use of Lendbreen.

Climate change may have had an impact as well. In 2017, Thun and Svarva reported that in the 1300s population declined in Norway. Tree ring data shows evidence of cold, wet summers. Historical sources report crop failures. Then in 1349, the bubonic plague hit Norway. These two events led to a demographic catastrophe. Such a catastrophe would have disrupted trade and travel.

That decline in population coincides with the start of the Little Ice Age (1300 to 1850). During this period, the northern hemisphere experienced a cooling. Scandinavia has a shorter growing season than does the Mediterranean. Lower temperatures and shorter growing seasons would be much more catastrophic in Scandinavia.

A more speculative explanation for the decline Lendbreen use

In 995, Olaf I Tryggvason, a Viking raider, returned to Norway as a baptized Christian. He seized the throne and began to impose Christianity on the Pagan population. That process took generations.

Interestingly for Pagans, the use of Lendbreen began to decline during this time of coercive conversion. No evidence exists connecting these two processes. They could easily be an odd historical coincidence with no causal connection.

Glacial Archaeology

Climate change is impacting archaeology. Northern latitudes have warmed faster than the rest of the planet. Glaciers have been melting and ice patches shrinking. Unlike soil, ice can preserve organic materials. Melting glaciers and ice patches have revealed organic materials in northern Asia, the Andes, and Europe. Perhaps, the most famous is Otzi, the “Ice-man,” found near the Austro-Italian border in 1991. Glacial Archaeology has emerged as a distinct field within archaeology but may have a limited lifespan. Archaeologist Lars Pilo has estimated that 90% of the ice in Norway’s high mountains will melt away by 2099. and thinks it’s too late to stop that loss.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.