TWH – A recent article published on the site on LiveScience.com reported on the interesting discoveries of the large Szigetszentmiklós-Ürgehegy cemetery (S-U cemetery) in Hungary. which dates to the Bronze Age.

Of particular interest were the contents of grave 241. It held the cremated remains of what the researchers referred to as “an elite female” as well as those of her twin fetuses. Pregnant for about seven months, she most likely died from complications of pregnancy or childbirth.

In Hungary, the Bronze Age lasted from 2150 B.C.E. to 1500 B.C.E. Archaeologists have already excavated 525 burials. Claudio Cavazzuti of the University of Bologna said that 1,000s of graves remain to be excavated.

Analysis of one grave provides an outline of a cremation ritual at the S-U cemetery. The research team used strontium analysis of a sample of the remains which helped to show migration patterns for high-status females. Strontium is an element that is highly reactive, chemically and is used in dating remains, especially teeth and bones.

Cremation Ritual

Most graves contained cremated remains. A few graves contained a complete, buried human body. An article in PLOS One described the outlines of a Bronze Age cremation and burial ritual.

The body would have been placed on a funeral pyre. The pyre would have burned for several hours. Sometimes, the fire reached a heat of 800o C (1472o F).

After the fire had consumed the body, someone would have collected the ashes, and any remaining bones and teeth. They would then place those ashes, residual bones, teeth, and any grave goods in the funeral urn.

The urn would have stood 35 to 40 cm tall (14 to 16 inches). At its widest, the urn would have measured 30 cm (12 inches). Inside or beside the funeral urn, someone would have set a small cup or dish. Two more cups would have sealed the urn. Next, they would then set the urn in the ground and bury it up to its neckline. Then, they would then cover the urn with stones, perhaps as a sort of grave marker.

While we can infer the basic outline of the cremation ritual, much remains unknown. We do not know who was present such as priests, mourners, or family members, for example, or what words were spoken.

LiveScience reported that the people of the Vatya culture built and buried their dead in this cemetery. They farmed, herded livestock, and engaged in both local and long-distance trade. They also built fortifications on parts of the Danube.

The S-U cemetery

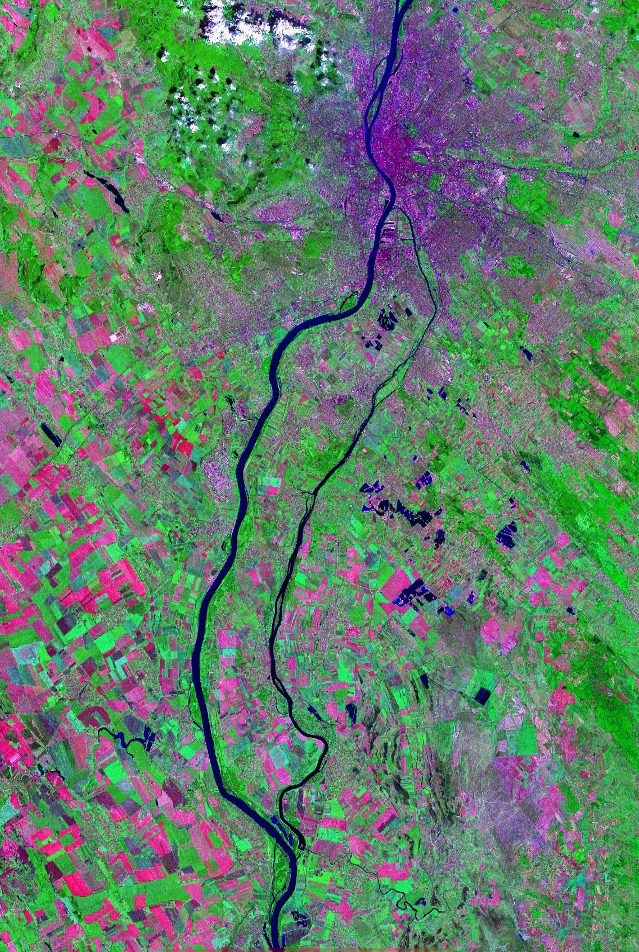

The article in the online journal PLOS reported that the S-U cemetery lies on the isle of Csepel, the largest island within the Hungarian Danube. On the eastern side of that island, another Vatya cemetery has been excavated. The two cemeteries lie directly opposite one another, along an East-West axis. Csepel Island lies just south of Budapest.

NASA satellite image of Csepel Island, Hungary [Image credit: Compactforever – Public Domain ]

Of the 29 analyzed graves, the three buried remains had decomposed too much to be examined. Archaeologists examined the sample of the 26 cremated remains in urns to estimate ages and biological sex. Among the cremated remains, 11 were female adults, seven were male adults, two had undetermined biological sex. Six were children. Among the cremated, 20 were adults, two were children between 5 and 10, and four were between the ages of 2 and 5. Note: the two fetuses were not counted in these age and biological-sex analyses.

While biological sex could be determined for most adult remains, gender identity cannot be known.

One grave stood out, grave 241. Unlike the other graves, the funeral urn in that grave contained more than one set of remains. It contained the cremated remains of one female and those of her two fetuses, as well as their grave goods.

An article in LiveScience.com reported that in that urn, they found a bronze neck-ring, a gold hair-ring, and bone pins. In the Bronze Age, these grave goods would have marked status. None of the other graves in the S-U cemetery had such high-status grave goods. The female buried in 241 would have been a member of the elite.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, her remains weighed 50% more than those in an average urn. This increased weight suggests a more careful post-pyre collection of her remains.

Strontium analysis to learn where she grew up

The cremation left some of her bones and teeth intact. That allowed researchers to conduct strontium tests. Those tests can reveal where someone grew up.

Researchers can analyze strontium “signatures” in bones and teeth. They then compare those levels with those in the soils of specific regions. Bones and teeth absorb strontium at different ages.

The soil in regions differs in strontium signatures. Plants in a given region absorb the strontium from the soil. Then, those plants store that signature in their tissue. When an animal or human eats those plants, those signatures pass into the creature eating the plant tissue.

Ráckeve-Soroksár Danube, Csepel Island (left) Molnár Island (opp.) from Vadevezős Street, Soroksár district, Budapest, Hungary. [Photo Credit: Globetrotter19 CC-ASA 3.0]

For example, the strontium signature formed in enamel no longer changes after youth. When researchers match that strontium signature in tooth enamel with strontium signatures in a region’s soil, they will have a good idea of where that person spent their childhood.

The strontium analysis showed that the female from 241 grew up somewhere other than Hungary. It showed a range of possible locations. Those locations ranged across Central Europe.

Her bronze neck-ring has a very similar style to those from southern Bohemia, Moravia, and Lower Austria. The strontium analysis included those three areas among her possible places of origin. The PLOS authors concluded that the elite female wore jewelry from southern Bohemia, Moravia, and Lower Austria.

She had moved to this part of Hungary between the ages of 8 and 13. She died between the ages of 25 and 35.

In contrast, metal workers from the Vatya culture almost certainly produced her gold hair ring. The presence of jewelry in her grave from both her “hometown” and her married life could have symbolic meaning.

The PLOS authors suggested that she could have brought the bronze neck-ring from her home village. It would have connected her to her origins. The locally produced gold hair-ring could have represented her new life.

Exogamy and patrilocality

Phys.org wrote that the levels of strontium in the remains of the adult females varied more than those of the adult males. Unlike adult females, adult males shared a common region of origin.

The authors of the PLOS study reported that exogamy (marrying outside the group) and patrilocality (the female moving to where the man lived) was common “across Bronze Age societies in Europe.” They suggested that these high-status marriages solidified alliances, economic, military, and political. This style of marriage lasted for 700 years.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Pingback: A Druid’s Web Log – September, 2021 Summer Comes to a Gloomy End – Ellen Evert Hopman