The timelines of three different video iterations of Superman are close to converging.

In Zack Snyder’s four-hour made-for-TV version of Justice League, Henry Cavill’s “Man of Steel” returns from the grave to brutally fight Jack Kirby’s 1970s space invaders while wearing Jon Bogdanove’s 1990s black “recovery suit.”

On the CW Network’s new Superman & Lois series, Tyler Hoechlin’s Clark Kent uproots his wife and teenage sons from their urban lives in Metropolis to what he hopes to be the simpler setting of the old family farm in Smallville.

For the upcoming Warner Bros. Superman big screen reboot, Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of Between the World and Me and We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, is writing– if one report is to be believed – the story of “a Black Superman.” Details to come.

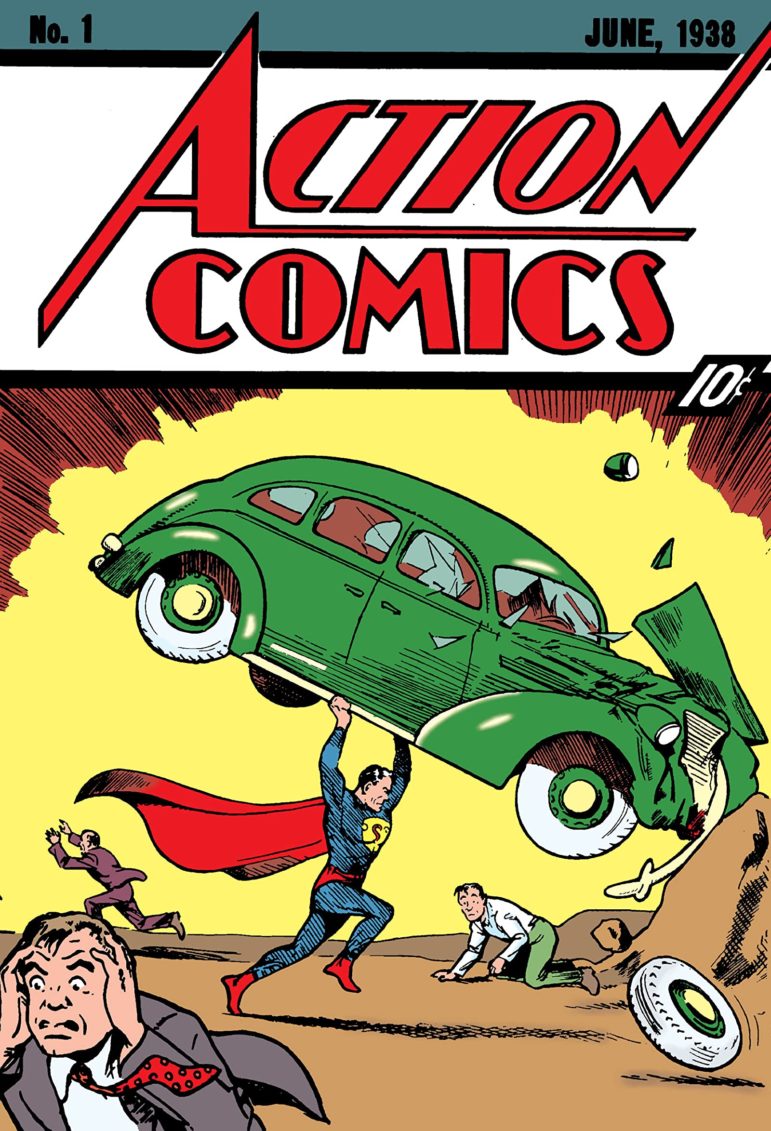

Superman’s first appearance on the cover of Action Comics No. 1 [DC Comics, used under Fair Use]

Eighty-three years after the first appearance of “the most sensational strip character of all time,” Kal-El of Krypton is still very present in the public dialogue of the United States.

What does our abiding fascination with this costumed character say about us? To address that question requires an understanding of myth and fairy tale.

Mythology and innumerable agendas

There is a multiverse of approaches to mythology that is as wide as human experience. Myths are seen as literal representations of reality, as mystic windows into numinous realms, as inspirational tales of ultimate hope, as rousing adventures of heroic figures, as literary cudgels that enforce social hierarchies – the list goes on.

Myths can also be read as records of religio-cultural worldview. For those of us interested in reviving, reconstructing, and/or reimagining Old Norse and Germanic religions, the myths and mythical poems that were preserved in Iceland provide valuable insight into the mentalité of late pagan culture even as they contain echoes of older paganism and connections to wider Indo-European traditions.

These archaic worldviews don’t necessarily line up with modern ones. The Old Icelandic Hávamál (“Sayings of the High One”) is an ethical guide for right living that diverges sharply from the Golden Rule; Þrymskviða (“Thrym’s Poem”) is an inversion of traditional masculinity that ultimately endorses it; and Skírnismál (“Sayings of Skirnir”) is a meditation on the union of opposites that privileges the demands of male desire and threats of violence against women.

Our reading of the old myths is ultimately done through the eyeglasses of our own worldviews. Modern Heathens focus on the positive elements of Hávamál and incorporate them into socially and digitally connected lives beyond the imagination of those who first composed the verses. Modern readers with sophisticated concepts of gender and sexuality celebrate the inversion of Þrymskviða without accepting the brutal machismo that concludes the poem. Practitioners of the new religious movement of Ásatrú retell the story of Skírnismál during ritual celebration in a way that embraces the union and elides the toxicity.

At its best, engagement with myth means examining the worldview of both the ancient world and our own. Mothers and grandmothers in India tell their children and grandchildren tales of Rāma and Sītā that are two thousand years old and more, shaping their retellings to shape the understanding of the next generation. One of the qualities of myth is that it is told and retold in varied forms in various situations while being deployed in the service of innumerable agendas.

Our view of the past is as fluid and changeable as our view of our own present and future. The stories that continue to have meaning in our lives have meaning because we invest them with meaning. The ways that we read them, hear them, and tell them simultaneously reflect our values and forward our values.

The Brothers Grimm understood this and acted on this.

Fairy tales and golden wisdom nuggets

In an 1811 letter, Jacob Grimm described the project of collecting “songs and tales that can be found among the common German peasantry”:

Our fatherland is still filled with this wealth of material all over the country that our honest ancestors planted for us, and that, despite the mockery and derision heaped upon it, continues to live, unaware of its own hidden beauty and carries within it its own unquenchable source.

As documented by Heinz Rölleke, Jack Zipes, and (more polemically) John Ellis, the Grimms edited and shaped the text known in the United States as Grimms’ Fairy Tales even before the first volume of the first edition was published in 1812. The “unquenchable source” of the “honest ancestors” was modified by modern minds shaped by in order to fit the Romantic nationalist worldview of the Grimms and their target audience of educated German readers.

1907 Heinrich Vogeler illustration of “Die Starntaler” (“The Star Money”) by the Brothers Grimm [public domain]

After 1815, Wilhelm Grimm became the major editor of the many later editions. He increasingly refined rustic elements into a more purely literary style, eliminated sexual situations, added romantic love, changed frightening mothers into evil stepmothers, and generally brought patriarchal elements to the fore. As the collection became increasingly popular with children, Wilhelm deleted fairies and added Christian proverbs.

The Grimms came to view their collection, according to Zipes, “as an educational primer of ethics, value, and customs that would grow on readers, who would themselves grow by reading these living relics of the past.” This is indeed how the text would be used in Germany and around the world. But the tales we are told as children – the so-called fairy tales that supposedly teach us basic moral values – are not “living relics of the past.” They are modern constructions that have passed through many layers of modern mediation before we come to know them.

The same is true of myth. The Old Icelandic poems and myths were not written down by pagan hands, but by Christians living more than two hundred years after the island’s official conversion to Christianity. There is no pure and original form for us to recover from the well of wisdom. There are only retellings of retellings, all the way down.

Zipes documents the amazing number and variety of revisions, rewritings, and restructurings of fairy tales in Germany since the 1960s. The list of modern German writers who have used the medium of the fairy tale as a vehicle for social comment and criticism is astounding. Rather than servicing an obsession with digging in the past in the hope of finding golden wisdom nuggets, the traditional form (as mediated by the Grimms) is used as a means of engaging with the world in which we find ourselves.

Here in the United States, stories of Superman function as both myth and fairy tale.

Superman as American myth and fairy tale

The Superman story radiates Americanness. Created by two sons of European Jewish immigrants and making his first appearance just one year before the Nazis invaded Poland and began World War II, the “strange visitor from another planet” has been associated from the beginning with immigrants who come to the United States and become key players in its self-made history.

Looking back at that first Superman story by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in the 1938 first issue of Action Comics, it’s amazing how little of the mythos is present. The unnamed “distant planet” of Superman’s birth is only mentioned in the first panel, the young alien grows up in an orphanage without the love of Ma and Pa Kent, and the hero is an adult by the fourth panel.

Kryptonite didn’t made its debut until a 1943 episode of The Adventures of Superman radio show, and didn’t make it into the comics until 1949, eleven years after the first issue of Action Comics. Supporting cast mainstays Perry White and Jimmy Olsen were both introduced on the radio show in 1940. Even the “faster than a speeding bullet” and “look, up in the sky” shticks originated with the radio show.

The ability to fly, which seems so core to the character, did not appear until Max Fleischer’s animation studios began working on their 1941 Superman cartoons and realized how ridiculous it looked to have the hero – according to the comics, only able to “leap 1/8th of a mile” – jumping around like a grasshopper on the big screen. The power of flight was then ported over to the comic books.

When the brilliant comic series All-Star Superman was first published in 2006, the mythology was so well-known that Scottish writer Grant Morrison could title his first issue “… Faster …” and present Superman’s entire origin story in four panels and only fifteen syllables: “Doomed planet. Desperate scientists. Last hope. Kindly couple.” Like regular churchgoers, we know all the details behind and emotional resonances of those few words.

This is how myth functions. By becoming part of this culture, the myth becomes part of us. By the myth becoming part of us, we become part of this culture. The myth both expresses the culture and spreads the culture.

This process can be seen in another late accretion to the mythos – the addition of “and the American way” to another of the character’s catchphrases.

The first issue of Action Comics calls Superman the “champion of the oppressed, the physical marvel who had sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need,” and the radio show called him a “defender of law and order, champion of equal rights, valiant, courageous fighter against the forces of hate and prejudice, who, disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth and justice.”

Kal-El has been a social justice warrior from the very beginning. His Jewish creators used the relatively new medium of the modern comic book to teach notions of tolerance and charity to young readers, and the radio show followed suit.

As nationalism soared during World War II, the radio show intro phrase was changed in 1942 to “truth, justice, and the American way.” After the war, the new addition was dropped – only to be added again for the opening of the Adventures of Superman TV series that ran from 1952 to 1958, coinciding with the rise of McCarthyism and renewed American nationalism during the intensifying Cold War.

In Superman Returns, the not-quite-successful attempt at rebooting the Superman film franchise in 2006, “the American way” was again removed – this time, under the shadow of vile human rights abuses by American military and intelligence personnel brought to light by CBS News in 2004.

This week, issue 16 of the Batman/Superman comic’s current run refers to Superman as a “champion of truth, tolerance, and justice.” Writer Gene Luen Yang has stated that he took the phrase from the 1948 Superman movie serial, but it also hearkens back to the decidedly liberal bent of the early radio show introduction and the very first published page of Action Comics.

Here, too, is the fairy-tale nature of Superman. As contemporary German writers have used the Grimms’ form to express their thoughts on modern life, American writers, artists, directors, and producers have used Superman to spread competing visions of what the United States is and of what we want it to be.

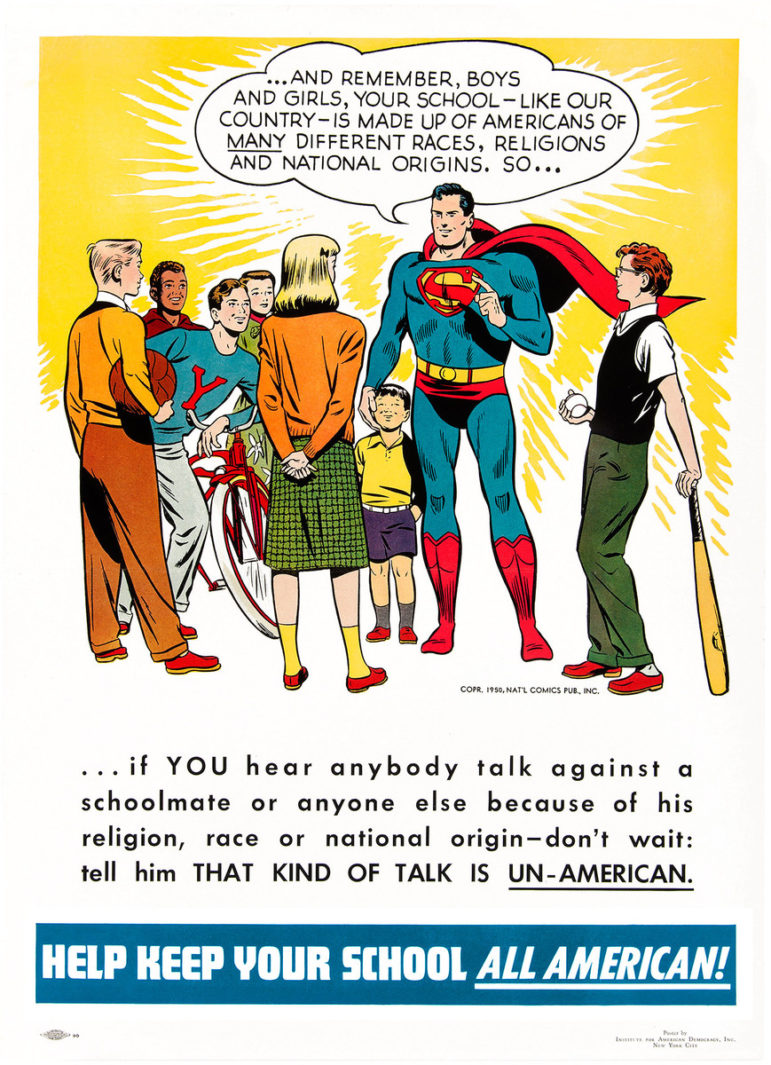

2017 restoration of 1949 Superman poster [DC Comics, used under Fair Use]

We are a nation of immigrants, but we are also an anti-immigrant nation. We celebrate our diversity, but we also breed white nationalist terrorists. We celebrate Superman as an orphaned immigrant who becomes an American champion, but we also lock up orphaned immigrants in cages – and even perform the orphaning ourselves. We design images of Superman teaching schoolchildren to celebrate diversity and confront bigots, but we also publish images of Superman actively promoting anti-Asian propaganda (trigger warning for the extremely racist images shown in the short documentary here).

Our myths and our fairy tales are expressions of our culture, and they spread our culture. The fact that American culture is complex and contradictory is neither unique nor a challenge to this understanding of the narratives we tell and consume.

The latest and upcoming versions of Superman on our small and large screens are part of this ongoing process.

Superman, Hooded Justice, and the Ku Klux Klan

Snyder’s Superman is black and white in multiple senses. In last week’s Zack Snyder’s Justice League, his traditionally tricolor costume has been reduced to black and white. In this week’s Zack Snyder’s Justice League: Justice is Gray, the entire movie has been reduced to black and white. It’s a bit on the nose to say that Superman’s morality has been reduced to black and white, but eight years after he snapped General Zod’s neck and five years after he killed (or didn’t kill) a terrorist by smashing his face through several walls, this version of Siegel and Shuster’s alien immigrant arrives at the end of the movie’s main action to slice off an alien invader’s body part and repeatedly pummel him as he lays unarmed and prone on the ground. This is not exactly a chromatic morality.

The CW’s Superman has a more considered approach to life’s challenges, as he’s pulled in multiple directions by his own internal moral compass. He wants to be a supportive stay-at-home dad for his two sons as they face the difficulties of their teenage years; he wants to support his wife Lois Lane as she pursues her journalistic career; he wants to help the people of the planet as they face natural disasters and unnatural threats; and he wants to aid governmental authorities while resisting the U.S. military’s impulse to treat him as a living weapon under their control. This is just in the first five episodes! I’ve never seen any film or TV version that came this close to representing the complexity of the character as he exists in contemporary comics.

It’s unclear what form Coates’ new cinematic Superman will take, but DC has already provided us with a contemporary take on a Black Superman. In the fantastic 2019 HBO Watchmen series – a sequel that was also a repudiation of both the original Alan Moore and David Gibbons comics and the Zack Snyder movie adaptation – the opening scene transposed the familiar Superman origin story to Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the race massacre of 1921.

Instead of a planet destroyed by natural forces, we see an African-American community destroyed by violently racist white men. Instead of a loving Kryptonian couple placing their young son in a rocket, we see a loving Black couple place their son in a basket on a car. Instead of a Kryptonian crystal encoded with a culture’s accumulated knowledge, we see a simple and heartbreaking handwritten note saying “watch over this boy.” Instead of finding friendship and love among his colleagues as a newspaper reporter, the hero faces intense racist violence from his colleagues as a policeman. The comics character and the HBO character both develop crimefighting alter egos, but only the Black one has to hide his face to avoid being lynched for his actions.

The fictional histories of Superman and Watchmen’s Hooded Justice converge on an interesting point: battling the Ku Klux Klan. Nearly seventy-five years before the HBO TV series, the Superman radio show featured a story arc called “Clan of the Fiery Cross” in which the superhero fought the KKK. In 1946, the series of episodes was produced at the request of the Anti-Defamation League, which had infiltrated the Klan and hoped that rightfully portraying the white supremacist organization as public enemies, terrorists, and ritual-obsessed weirdos would destroy whatever mystique they held in the minds of American youths. In 2019, Hooded Justice’s battle against a KKK conspiracy is shown to take place at roughly the same time as Superman’s.

As with Gene Luen Yang’s return to the late 1940s concept of Superman fighting as a “champion of truth, tolerance, and justice,” the producers and writers of the Watchmen TV series nodded towards the part of the Superman myth that most clearly speaks to and stands against the resurgent white nationalist terrorism of today. Interestingly, Yang also authored the 2019-2020 comic book limited series that adapted the 1946 “Clan of the Fiery Cross” radio episodes as Superman Smashes the Klan. He has said part of what drew him to the story was discovering that, in the original radio programs, it is a Chinese-American family that moves to Metropolis that first gets Superman involved in fighting against the KKK.

The myth and the fairy tale are retold yet again, in new forms that refer back to the old.

Brutality and maturity

I became a Superman fan in 1976 or 1977. Since then, I’ve been reading Superman comics and watching every possible cartoon, television, and film version of him. When I was in preschool, I tied a blanket around my neck as a cape and jumped off of chairs as I yelled, “Supermaaaaan!” Long before I knew about Thor, Zeus, the Abrahamic god, or Jesus, I knew about Superman.

From the very beginning, he was defined by his amazing abilities and by his kindness. When I saw the first Superman movie in 1978, it wasn’t just the flight scenes and special effects that I loved. It was also the smile and the wink when he looked out at those of us sitting in the audience.

I drifted away from Superman in the early 1990s, both because I was too busy building a life and because I thought I was too cool for the straight-ahead character. I came back into the fold with Superman volume 2, issue 175, in December, 2001. I randomly picked it up in a comics shop and was shocked to see that Lex Luthor was president and that American colorists were using computer tools to render three-dimensional effects.

After that, there was no escape. The fact that DC has repeatedly brought in top writers and artists to create mature tales dealing with complex issues made a big difference. Sometimes the stories soar, sometimes they fall flat. Such is the nature of our retellings of myth and fairy tale.

Today, I’m completely turned off by the Synder version of the character. He seems too indebted to the übermacho and ultraviolent comics of the 1990s, full of protagonists with bulging neck veins grimacing like they’re in the midst of an extremely painful proctological exam. The Snyder Superman who shows up in the final moments only to beat someone nearly to death is far less interesting to me than the CW Superman who remains present and works to do the right thing by his family, his country, and his planet while holding on to his core values.

The snarling and weaponized Superman is too much an embodiment of the worst elements of the United States today, and I can find no connection with him. I know that the 1977 version of me would have been absolutely terrified of him. On the other hand, the thoughtful and determined Superman is the latest version of the Superman I have known and loved for nearly fifty years. He has points of contact with the positive elements of the character that have appeared for over eighty years.

Today, our nation is divided. The division between these two iterations of Superman both reflect that division and forward that division. As we’re surrounded by anger and submerged in hate, the last thing we need is a dark and almost amoral Superman. I’ve been working to convince family and friends to watch the kind and caring Superman. He’s the one I’ve always known.

Our myths and fairy tales reflect us, and they way that we tell them shapes us. Who are we today, and who do we want to be?

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.