Looking back, one of my all time favorite childhood memories is of one of those seemingly endless summers one often experiences in southernmost France. While I liked to spend these days going out in nature and to the ruins of the medieval castle, my favorite activity was actually to go the local library’s garden, grab a couple of comics, and sit in the sun.

There, I filled my mind with pictures of real and imaginary worlds while listening to the soothing piano sounds coming from the music school on the other side of the garden, and I could spend time completely at peace. Among other things, I distinctly remember devouring entire series of comic books, among which few, if any, I liked as much as Asterix the Gaul.

While Asterix is not very well known on the western side of the Atlantic, in Europe, it enjoys a cult status that can only be compared to the most recognizable properties from Disney, Marvel, and DC. The comic, originally written by René Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo, originated in the bustling postwar Franco-Belgian comic book golden age, where countless classics such as Lucky Luke, Blake and Mortimer, or the Smurfs came to life. Like many other bande-dessinées of its time, Asterix was set in historical times, in ancient Gaul, and in just about every volume, one character or another utters the now legendary exclamation: “By Toutatis!”

Describing Asterix solely as an adventure comic set in historical times would be very misleading. What Goscinny and Uderzo created more than six decades ago transcended the media their creation was born in and became nothing short of a cultural juggernaut. Even following the death of Goscinny in the seventies, the series continued, now with Uderzo taking care of both the writing and the drawing. Following the disastrous review of the 33d album (Le ciel lui tombe sur la tête) in 2005, Uderzo announced he would let new creators take the series forward.

Then, in March of 2020, the cartoonist passed away in his residence of Neuilly, aged 92. When I learned about the tragic news, I was immediately taken back to my childhood days of browsing his amazing series, and I realized that it actually had played a not-so insignificant role in turning me towards the Old Religion. I would like to convey how, with the help of funny-looking cartoon characters, a young lad living in the middle of nowhere in a time before the internet could discover a world well beyond his own.

The first thing to know about Asterix is that, despite being set in ancient times, it tells just as much, if not more about the time it was written in. A number of volumes present, and subsequently parody, various modern issues and themes, such as capitalism (Obélix et compagnie), modern urban planning (Le domaine des dieux), terrorism in Corsica (Astérix en Corse), shady banking secrecy (Astérix chez les Helvètes), and much more. One could even argue that the very idea of a comic idealizing prideful Gaulish warriors resisting the power of the Roman Empire is based on a modern interpretation and utilization of history.

A selection of European hardcover Asterix albums [L. Perabo]

In France, when the republican institutions were reestablished for the third time at the end of the 19th century, the state engaged in a significant process of centralization. To bring the people of a divided country together, new, yet ancient, symbols were needed. It could not be the monarchy, as it had become rather controversial, to say the least, and it could not be Joan of Arc, because of her ties with Catholicism. So the fierce and prideful Gauls were chosen. For the following decades, French schoolchildren (myself included) all started their history education by hearing “nos ancêtres les Gaulois” (our ancestors the Gauls) in the nation’s classrooms.

This somewhat national-romantic origin story of the Gaulish French, coupled with a number of totally anachronistic details splattered all across the series – such as the appearance of Vikings, some 800 years before their time – could well have been expected to become a terrible medium to learn about history, but Asterix is anything but that. Through humorous and colorful strips, I remember learning about Caesar, Brutus, Cleopatra, Gallo-Roman culture, and also, religion.

While religion in and of itself is really not all that present in the pages of Asterix, we find elements of it tucked away in just about every corner. Just the aforementioned “By Toutatis” exclamation – sometimes followed by “By Belenos” or “By Belisama” – probably did more to raise the awareness of this long-forsaken god than centuries of scholarship and renewed worship combined. In addition, every time Asterix and his friends ventured into another land, the locals would similarly swear by their own gods: Venus, Indra, Ahura-Mazda, Poseidon, Odin, Thor, Osiris, and more. The list is so large that someone even bothered to write a detailed Wikipedia article article about it.

Another aspect of the world of Asterix that fascinated me as a child is that it was entirely set in a world free of Christianity. With the exception of a few strips in L’Odyssée d’Astérix that take place in the Middle East, there is not a single passing reference to anything biblical either. For a child, the colorful world of comic books is bound to be interpreted crudely to start with, and yet, the depiction of a world where people are neither threatened by menacing clerics nor guided by the iron law of obscure religious texts was a breath of fresh air.

In contrast, the way Asterix and his Gaulish friends spent their days traveling all across the world (reaching places as far as India or North America), making friends with locals, fighting emperors, blood-thirsty chieftains, and treacherous politicians presented maybe the most positive image of diversity one could think of.

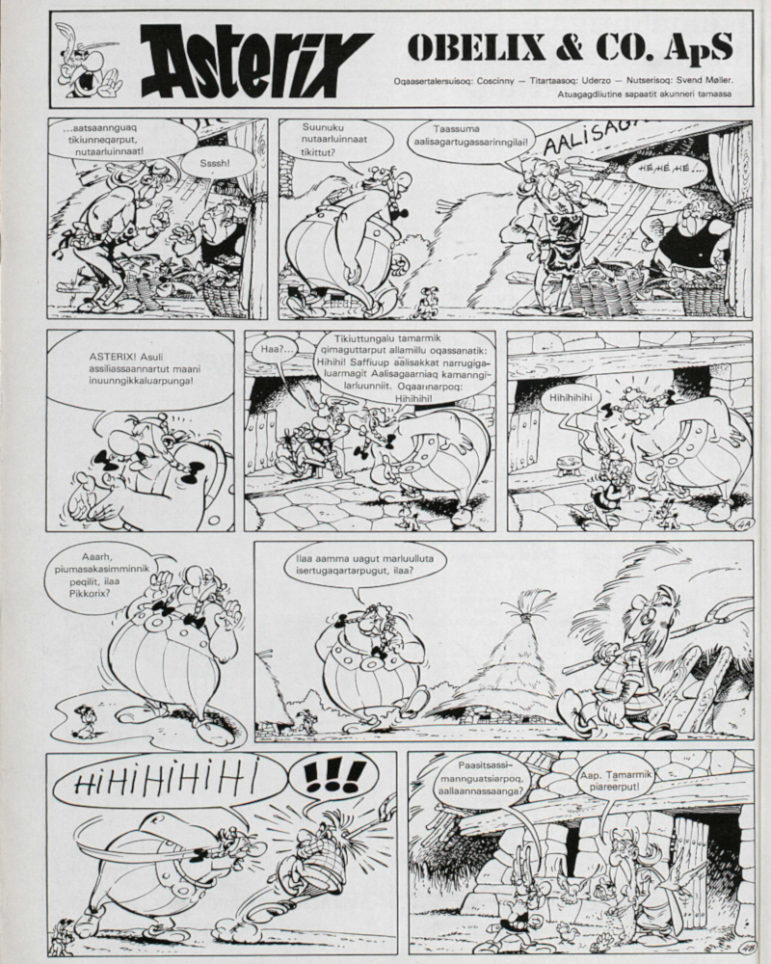

A newspaper edition of Asterix in Greenlandic [Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten]

Even when Asterix and company peacefully stayed at home in their Gallic homelands, I would always find more than enough themes and narratives to quench my thirst for obscure knowledge. In the first pages of the very first volume, the readers of Asterix are introduced to Panoramix (Getafix, in the English translation), the titular druid of Asterix’s village. This old wise man, not too dissimilar in nature to Gandalf or Merlin, is the one who brews the powerful magic potion that gives near-supernatural strength to the villagers, thus allowing them to remain independent from the neighboring Roman Empire. To say that this character plays a central role in the series would be an understatement, and numerous albums (my favorite of which being maybe Le combat des chefs) focus on this very druid, and how critical his work is.

While practitioners of the Old Religion are not always depicted in a wholly positive light in the series (the hilariously charlatanical new-agey soothsayer in Le Devin being a fitting counterexample), the fact that a druid is presented as the guardian of the independence, identity, and freedom of his people left a powerful impression on me. Maybe druids were actually not just dangerous human-sacrificers, like I had learned in school? And maybe there was something behind this cartoon character that reflected something true, and positive about this long-forgotten worldview?

I am more than certain that, of all the kids who got their hand on an Asterix album, I must not have been the only one to have had these kinds of thoughts. The mind of children is, at the end of the day, infinitely malleable, and these small ones absorb just about everything in their environment, consciously or not. I also feel that this experience is probably not all that dissimilar to that of American Heathens who first discovered Norse myth through Marvel’s Thor. Maybe, just maybe, all these works that were at the onset intended to be mere entertainment, might actually have acted as some sort of trigger in the impressionable minds of children inclined towards something a bit more spiritual?

Years after discovering Asterix, when being introduced to philosophy, fairy tales, and the history of religions through my nifty niche high school study program, I ended up falling deep into a rabbit hole made of occultism, Paganism, and Celtic culture. Would I have become that interested in the obscure world of the Old Religion if my childhood cartoon hero had been a monk or a crusader? Fat chance of that I think. And yet, even if this is the one aspect of Asterix I feel has had the biggest influence on me, the true legacy of this comic is that it somehow managed to appeal to people of all backgrounds, all over the world.

Sixty years after its creation, Asterix has been published in over 50 countries and 100 languages, including an impressive number of dialects (Frisian, Karelian, Scots), languages (Greenlandic, Indonesian, Basque), and even dead languages (Latin, Ancient Greek, Proto-Celtic). Any parent wishing for their children to develop their intellect, artistic sense, historical knowledge, and interest for Paganism would be well-advised to pick up a volume or two of this excellent series that is guaranteed to lift the spirits, and elevate the mind.

As a freshly-baked father myself, I cannot wait to introduce my child to this treasure trove. While I personally ended up more closely bound to the Northern tradition than anything else, perhaps my child might end up turning her sights to the other side of the fence and unto the green grass of Celtic mysteries? Who knows, but until then, I give my thanks Goscinny and Uderzo for helping me, and I am sure many others, find the way.

The Wild Hunt always welcomes guest submissions. Please send pitches to eric@wildhunt.org.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.