Fifty years ago today, human beings first walked on the Moon.

Strange, how simple that sentence reads, in comparison to the monumental consequence of what it describes: on July 21st, 1969, for the first time in human history, members of our species set foot upon the ground that did not belong to the Earth. It remains one of the greatest scientific and engineering feats yet accomplished by our species, and even now retains an aura of awe and wonder that most things from the late 60s have failed to keep.

It has always struck me that the names NASA chose for these endeavors drew upon Pagan gods for their inspiration: Mercury, Saturn, Apollo himself. Abe Silverstein, NASA’s headquarters director of space flight programs, supposedly chose the name one night in 1960 while browsing through a book of mythology at his home: he claimed that the image of “Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program.”

Apollo, often identified as a god of enlightenment (and, for that matter, the Enlightenment), is identified with all sorts of spheres of influence – he is a god of archery, poetry, shepards, healing, and many more – but it is perhaps in his role as oracle that he is ultimately most appropriately seen as the patron of the lunar landing. Oracles are the figures we turn to for knowledge that we already carry within us but need an outside perspective to understand.

The Earth is small. We know this, intellectually – that there is only so much land and water contained on our planet, that within our solar system the Earth is dwarfed by the size of the sun and the gas giants, which we named for gods like Jupiter and Neptune. We know that the Milky Way contains hundreds of billions of stars, of which our sun is just one, and that there are perhaps another hundred billion or more galaxies in the observable universe. These are facts, or at least, they are the best approximation of facts available to us given the information to hand. Much of this we have known since decades before the Apollo program sent humans to the Moon. But the difference between intellectual knowledge and emotional knowledge is vast.

“Earthrise,” taken by William Anders during Apollo 8 [public domain.]

Earthrise, as this photograph is known, was taken by William Anders on a flyby of the Moon during the Apollo 8 mission. Although a postage stamp identified the image with the Book of Genesis, Anders himself found that seeing the Earth from the outside make him question his religious beliefs: “The idea that things rotate around the pope and up there is a big supercomputer wondering whether Billy was a good boy yesterday? It doesn’t make any sense.” I can understand how seeing the Earth from such a distance could undermine one’s belief in an all-powerful and transcendent deity, especially one much concerned with an individual human’s conduct in life; just the sight of the Earth from the Moon makes one understand on an immediate level all the intellectual truths of the Earth’s smallness.

On the other hand, to my Pagan eyes, Earthrise is as powerful an encapsulation of my religious ethics as any chant or sculpture. Here is the Earth, this tiny ball of life in the great darkness of space. See the sphere, and then see how everything on it is connected, is related to one to another, is responsible for one another.

We may know this intellectually, even morally – but it’s striking how obvious, how inarguable, it becomes when seen from the outside. Apollo gave us that.

The famous “Blue Marble” photograph, captured by the crew of Apollo 17 [public domain].

I loved space when I was a kid. I fell for the wonders of stars and planets and moons long before I understood anything about the religion that raised me. When people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I told them I wanted to be an astronomer. (Even at a young age, I realized I’d never be in the right kind of shape to be an astronaut.) My favorite book was a copy of H.A. Rey’s The Stars: A New Way to See Them, a book about constellations that tried to teach them as simple stick-figure illustrations of the characters from Greek myth for whom they were named. It was my first book of mythology, in its way. My Paganism has always been rooted in the stars.

I never did become an astronomer. But looking back at the history of the Apollo program now, a half-century on from its greatest success in Apollo 11, what strikes me is how the images captured by the program retain their sense of majesty, wonder, and the sublime. The Blue Marble photograph, captured on the final Apollo mission, Apollo 17, is at once gorgeous and terrifying to behold. Our eyes can see all of Africa at once – all of it. It’s where our species first evolved, where 1.2 billion of us live today. Look how much is there, and how little.

How wonderful the Earth is. How terrible. How sacred.

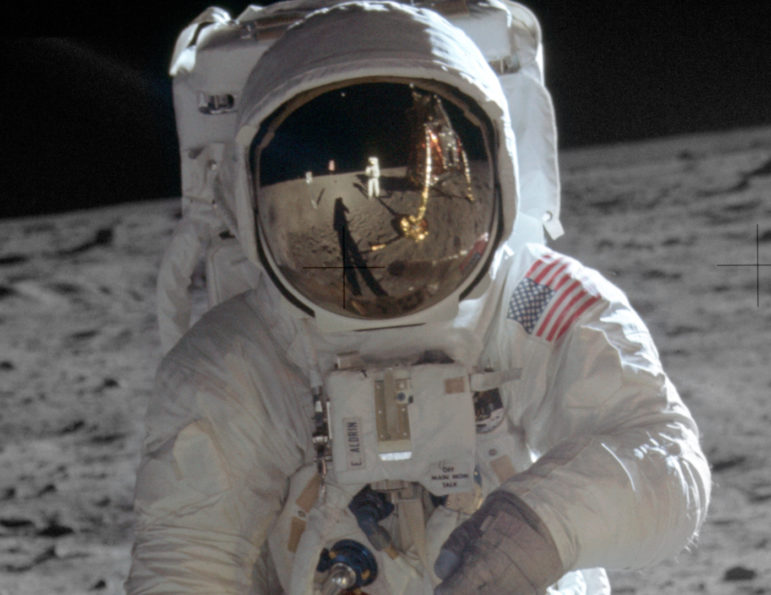

Buzz Aldrin, with Neil Armstrong, the photographer, reflected in his visor – a self-portrait of sorts, taken during Apollo 11 [public domain].

Fifty years ago today, humans first set foot on the Moon, the culmination of a project that employed hundreds of thousands and required more than $150 billion in today’s money. They came in peace for all mankind; the came to show the Russkies the superiority of American capitalism. One in five humans living at the time watched Neil Armstrong take that famous “small step for man.” And then, by and large, they lost interest; we left the Moon in 1972 and haven’t been back since.

The legacies of Apollo are too complicated for any one writer to tackle in a few hundred words, but let me close with this. In the name of Apollo, god of verse, prophecy, and knowledge, we sent human beings to set foot on the Moon. But what caught the astronauts’ eyes, as much as the Moon itself, was their ability to stare back at the mother planet from which they had come – a reflection of humanity that had never to that point been seen. Even now we look at the photographs of the Earth from space, and we marvel at the sight.

“Wow,” as William Anders said when he first saw the Earth rising. “That’s pretty.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.