PLOUGASTEL-DAOULAS, FRANCE – It’s the height of strawberry season in northwest France, and in the village of Illien ar Gwenn farmers are busy harvesting their famous gariguette de Plougastel variety of the berries. The village, part of the city of Plougastel-Daoulas, lies in the canton of Guipavas, southeast of Brest, in the Brittany region.

While the delicious berries are one of the region’s most famous attractions, it has recently gained notice for something else altogether. A puzzle has emerged, with a reward of €2,000 (about US$2,275) attached, to anyone who can solve it. It might just be the sort of puzzle Pagan polyglots could help with.

Located due south of Cornwall, England, just over the English Channel, the region of Brittany is the only continental foothold of the six Celtic nations, those regions and nations that have a surviving Celtic language.

Those six nations and their Celtic languages are well-known to many Pagans who are students of ancient Celtic history. There are two main branches of the modern Celtic languages: Brythonic and Goidelic.

The Goidelic, or Gaelic, languages are Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), and Manx (Gaelg). The Irish langauge has a healthy population of about 1.7 million speakers, while Scottish Gaelic still has a population of some 60,000 fluent native speakers. Both are listed as endangered and definitely endangered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s Atlas of World Languages, respectively.

Manx is extinct. The last native speaker of Manx, Edward “Ned” Maddrell, died in 1974.

Plougastel-Daoulas (User Pretorien0, Wikimedia Commons)

The Brythonic languages are Breton, Cornish, and Welsh. Cumbric is part of this language set, but it became extinct in the 12th century CE. Cornish became extinct in the 18th century; it has experienced a revival, but there are still less than a thousand speakers. Welsh is the national language of Wales, currently approaching a million native and second-language speakers. It remains endangered nonetheless, especially because of a persistent socio-economic preference for English.

That brings us to the southernmost of the modern Celtic languages, Breton or Brezhoneg. Breton, as a language, is alive but struggling. It is listed as “severely endangered” by UNESCO.

The number of Breton speakers has fallen precipitously over the last half- century. Around 1950, there were approximately one million speakers of Breton in the regions of Brittany, Pays-de-la-Loire, and Île-de-France. Today, that number is about 230,000.

There is some hope for the future of Breton with the introduction of bilingual education. The challenge remains for Breton (and for all the Celtic languages) as to whether the acquisition of any of these languages produces avenues for economic opportunity.

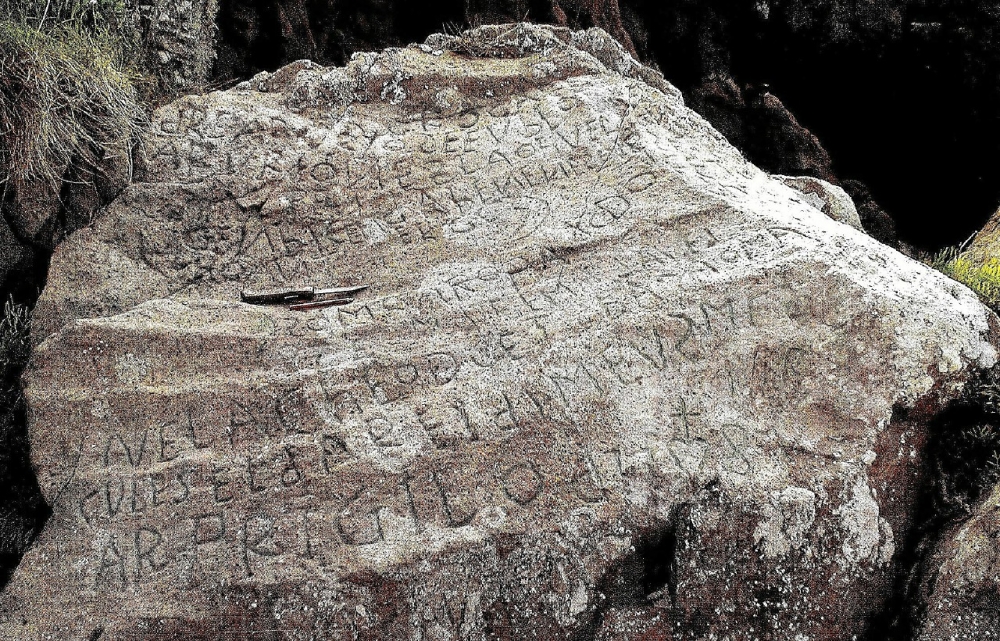

With that covered, onto the puzzle. Discovered in 1979 at a local beach in Illien ar Gwenn, there is a boulder that is visible only at low tide. The boulder is a little over a yard (one meter) in height, and is located to the north of Pointe du Corbeau along the eastern side of the Roadstead of Brest (La Rade de Brest). The area is what might be described as a series of smaller peninsulas on the peninsula of Brittany.

The inscription uses the Latin alphabet for all but one letter, an Ø. All the letters are capitalized. There are some visible numbers that are apparently dates: 1786 and 1787. The rest of the inscription is 20 lines of indecipherable text. Part of it reads “ROC AR B… DRE AR GRIO SE EVELOH AR VIRIONES BAOAVEL… R I OBBIIE: BRISBVILAR… FROIK…AL.”

Part of the inscribed boulder (Courtesy Commune Plougastel-Daoulas)

“We have asked local historians and archaeologists, but no-one has been able to work out the story regarding the rock,” says Dominique Cap, mayor of Plougastel, who spoke with Hugh Schofield of the BBC. “So we thought maybe out there in the world there are people who’ve got the kind of expert knowledge that we need. Rather than stay in ignorance, we said let’s launch a competition.”

The listed dates may be important. During the long wars between England and France in the 18th century, the area around Brest saw many naval fortifications, and some think this may explain the presence of the stone. “These dates correspond more or less to the years that various artillery batteries that protected Brest and notably Corbeau Fort which is right next to it,” said Veronique Martin, the town official responsible for the deciphering contest, to agence-France Presse.

The inscription also includes two images. One appears to be sails and a rudder. The other image is a sacred heart.

Martin has contacted historians and linguists who have yet to provide a solution to the puzzle. Even the language used in the inscription isn’t clear. “There are people who tell us that it’s Basque and others who say it’s old Breton,” said the mayor.

It also unclear if the author was literate or semi-literate; the author may have composed the words phonetically. “There are a lot of words, they’re letters from our alphabet, but we can’t read them, we can’t make them out,” said Michel Paugam, the local historian.

The contest is officially called “The Champollion Mystery at Plougastel-Daoulas,” named after the 19th century French historian and linguist Jean-François Champollion, who deciphered the Egyptian hieroglyphs of the Rosetta Stone.

Anyone interested in working on the code can register at the mayor’s office. About 600 individuals have already started. The contest will conclude in November when a panel of experts will review submissions and select the most plausible interpretation.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.