The phrase has come across my radar so often that it could have been confused for a spaceship in the skies of New York: “2018 was the year of the Witch.”

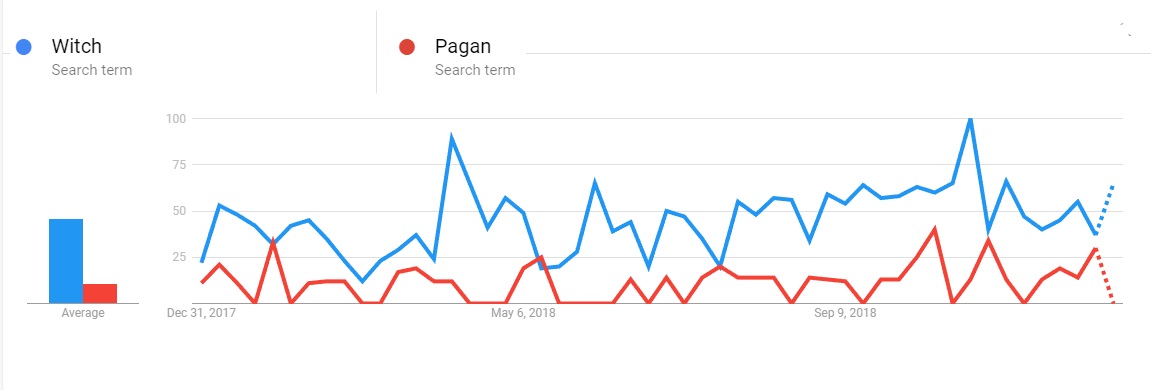

My apologies to the rest of the Pagan, Heathen, and polytheist landscape, but the combined powers of pop culture and politics have made their pronouncement: “Witch” was the most prevalent term associated with Paganism over the past year, even, as Google Trends show us, surpassing the word “Pagan” itself. But while “Witch” can stand out as a term on its own, its ascendance was propelled by related terms like “scarlet” and “teenage.”

The undeniable popularity of Netflix’s Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, along with the subsequent lawsuit by the Satanic Temple for the show’s use of a Baphomet statue, has attracted a great deal of attention to Witchcraft. The remake of Suspiria also contributed, but, I suspect, mainly in circles of cinephiles.

Google Trends

While these fictions may be fueling much of the current Witch craze, they are not the only Witchcraft topic that the public is discussing lately. Witch mainstreaming was augured by Naomi Fry’s piece in the New Yorker discussing Frances F. Denny’s portrait exhibition “Major Arcana: Witches in America”. (Sephora capitalized on the opportunity, you may recall, by attempting to offer a “Witch starter kit.”) Halloween and Netflix followed, culminating in Newsweek’s declaration that Millennials were rejecting Christianity and that the number of Witches was “dramatically” on the rise in the United States. Quartzy goes further, identifying the rise in the U.S. Witch population as “astronomical”.

Just yesterday, the Denver Post reported that Witches are coming out of the broom closet and reconnecting with the Earth because of this moment:

Once unmentionable, witchcraft is now trendy, witches and academics who study the craft agree. It’s having a moment, not just in Denver, but in the broader culture — enchanting a new generation of magic-seekers and affording mature practitioners the chance for more outspoken coven lovin’.

“It is showing up everywhere, for sure,” said Rory Lula McMahan, a pagan priestess in Denver. “It’s hip and cool and faddish, and I have mixed feelings about that. … It means the mainstream is shifting, and there’s more acceptance and exploration, but I also worry a witch being faddish means people think listening to Stevie Nicks and wearing black lipstick is what it’s all about.

Newsweek thinks that the rise in interest in Witchcraft is the result of post-modern avoidance from repressive Christian beliefs – that is, Witchcraft exists as an inclusive, counter-cultural, free thinking, semi-religious echo of nature-worshiping Indo-European cults.

To me, that’s an idiopathic and patriarchal explanation for the current interest in Witchcraft by the mainstream culture. Fads come and go, but they arise by allowing some expression of personal agency that is unfulfilled by the current social architecture. Faced with an unrelenting misogynistic assault on women’s lives and bodies, a rise of racism and nationalism, and constant attacks on non-binary spaces, it has become clear to many that new strategies for protection are needed – strategies that could provided by Witchcraft.

I don’t think that the current interest in Witchcraft is being driven by religious longing. I think it’s driven by a need for protection captured uniquely by one thing: the hex.

From the legendary (in more ways than one) Operation Cone of Power to Witches gathered in front of Trump Tower in 2016, Witchcraft is about resistance. Witchcraft converts helplessness and hopelessness into empowerment and action. Witches take on the weight of reality and demand the impossible occur.

The fear invoked by the opposition to Witches has raised our collective prominence. As some Christians – and Christian Nationalists – attempted to protect Donald Trump from magical attack, the public was left wondering why Witches were so dangerous and, by proxy, effective. Trump’s growing paranoia about opposition – and his distasteful use of the term “witch hunt” to suggest that men are the true victims of the #MeToo movement – only underscore the effectiveness of the hex as a tool for resistance. One could say the same for Rev. Pat Robertson’s never-ending concerns over all things witch.

By the middle of 2018, Witches had opened a new front, this time against the National Rifle Association. Two months later, other Witches took magickal actions against the then-nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh. What mattered in both was the attention each act brought to Witchcraft.

For some individuals, ritual became something to do when there was nothing left to do. Witches came into that space of resistance like cavalry.

Hexing has shown that, even when one lacks broad platforms and money, there is still a magickal and spiritual arsenal available.

Was 2018 really the “year of the Witch?” Well, I think some good things did happen. The mainstream presence of Witchcraft helps all communities that are part of the Pagan umbrella, and the attention even helped bring about reforms like good things happened like the ending of Witchcraft laws in Canada.

I’m still hesitant to call 2018 the “year of the Witch,” however, for three reasons.

First, there is how Witches are portrayed. As stories emerged over the past year, the media found it irresistible to add both classic portrayals of witches (think Hansel and Gretel) and snarky commentary to its descriptions of Witchcraft. One would think there would be an attempt to keep an enlightened tone, and yet some kind of ridicule or micro-aggression always sneaks in. Real Witches are becoming more seductive to the media, but apparently, the stereotypes remain moreso.

Second, there is the whitewashing of Witchcraft. There is no shortage of Witches of color and no dearth of traditions from which they emerge; from Hoodoo to Wicca to African Traditional Religions to Eastern paths, there is no culture that fails to have a Witchcraft tradition in it. And yet there is a constant return to the white Eurocentric depiction of the witch as the standard bearer for all of Witchcraft.

Third, there is the sanitization of Witchcraft. When the media focuses on the experience of Witches in privileged spaces – which can involve only showing Witches in Western democracies or professional-class suburbia – it neglects the reality that many Witches face discrimination, danger, and poverty. Witchcraft is a dangerous practice fraught with physical and economic hazards. Witches experience social isolation due to overt threats even in places that secure religious freedom like much of North America and Europe. Elsewhere in the world, the practice of Witchcraft can be a death-sentence for women and children. Yet these realities are almost never acknowledged in mainstream portrayals of what it means to be a Witch.

In the end I disagree that 2018 has been the “year of the Witch.” We need improvements in terms of representation and real advances within our community before I would feel comfortable using that phrase. 2018 was a year, however, where one tool of Witchcraft did bring the whole tradition to prominence. “In a country where they turn back time,” as Al Stewart once said, 2018 was not the “year of the witch” – it was the year of the hex.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.