Pagan Perspectives

A few years ago, I was visiting a Pagan event, which will remain nameless. The event was well-patronized and filled with participants from all sectors of our community writ large. It was organized by an amazingly competent team who were sensitive and caring. There were carefully prepared spaces that I am sure you have heard of, red tents to male mysteries. I visited one of these, the Pagans of Color safe zone, and was asked to leave; I was told the space was not meant for “straight white dudes.” (I am gay and multiracial, and while I have in rare cases been called a “dude,” it is not in any top ten list of nouns for me.) So I left. I got effusive, embarrassed apologies about an hour later.

This is not a finger-pointing essay. What happened then ended then as well – it was a mistake. The organizers intended to create an inclusive space, but their practice was inconsistent. Sometimes that happens.

Over the past year, however, in what feels like too many times, we have had to stare down a very blunt question: are we really an inclusive community? I would like to think that, in a general sense, we are. We have work to do, but I think many in our community are working to raise awareness of the need to be inclusive. That is challenging, though, because inclusivity is both unfamiliar and recent.

Let’s face it: inclusivity is a new concept, as new as Neo-Paganism. It doesn’t even show up in my Google Chrome dictionary.

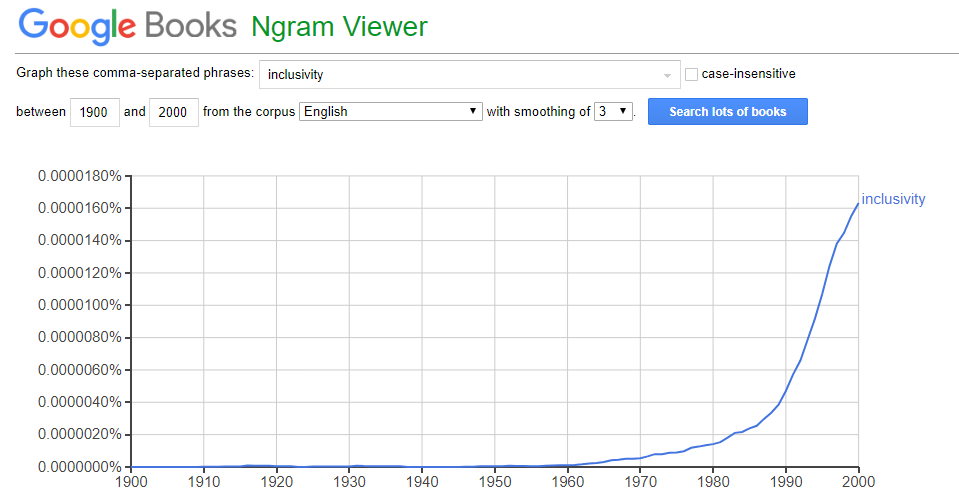

The word jumped into the English language sometime around 1929, first used as a reference to “inclusiveness,” itself a word that entered English use only about a decade earlier.

We can see that emergence in Google’s ngram viewer for books.

Source: Google. (Run it yourself here.)

I don’t have data for other languages, but if terms like “leadership” can serve as guide, terms like this begin co-occurring in multiple cultures as a sort of zeitgeist.

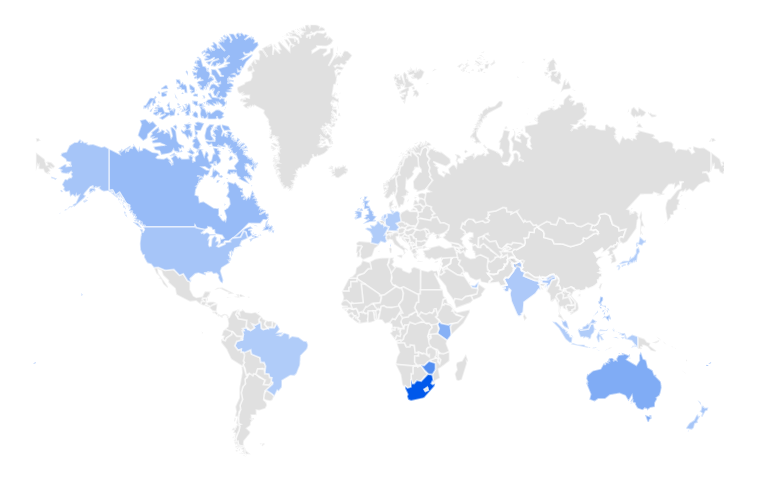

It is a mood that continues today but is far from universally explored or understood. These are the searches for the term “inclusivity” since 2004 (the earliest available date) on Google Trends:

Source: Google Trends. (Knock yourself out- it’s very fun.)

It is an obvious map of where that dialogue is urgent as well as where that dialogue has yet to happen – in the Anglophone world, anyway.

My take-away from all of this is that our world is still struggling with the concept of inclusivity. Entwined in this concept are difficult reminders of power, privilege and history. I also think that many in our community – if not most – recognize the barren theology of using DNA, birth sex, or nationality as defining characteristics for spiritual practice.

I wasn’t sure another essay on this topic would really add to the conversation in our community. Then, literally a few minutes ago, in the life of this essay, that doubt was starkly focused. As I write, I am on the water and anchored in Biscayne Bay. For context, my boat is unnamed. It only has the manufacturer’s decals on it, the name of its home port of Miami, and its vessel numbers – no flag, no markings, nothing. I’m catching up on my email in silence, no music playing. There’s nothing that says “Witch on board” or “Pagan present”.

For those not familiar with boating, there is unspoken gentility that occurs as boats go past each other – captains are expected to wave. A high-end boat went by bearing a flag that looked like a Thor’s hammer over crossed bones. It caught my eye. When I looked up, the captain and mate saw me. I waved, and the two white men smiled back. One lifted his beer, and then both waved back with OK signs.

There it was: a flag adding possible context to an unclear communication, raising questions about inclusivity. Was it intentional? Was it a hoax? Were they trolling? Did they know the current conversation about the meaning of that gesture? Were they just saying “okay,” or were they invoking some skin-color solidarity? I have no idea.

What I do know is that their gesture created a barrier between them and me. Their “okay” turned a friendly greeting on the water into something else. They created a space, intentionally or otherwise, where I had to wonder if I was welcome. It reminded me that inclusivity is more crucially an action rather than a belief or desire. We cannot have an inclusive community without the acts that create one.

Inclusivity is practice, a point that I think is easily forgotten in favor of the easier stance of belief. The point is echoed by the Oxford English Dictionary, which defines inclusivity as “the practice or policy of including people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized, such as those who have physical or mental disabilities and members of minority groups.”

Those practices have also been described. Almost two decades ago, the Association for the Study and Development of Community, in collaboration with the Ford Foundation, the Meyer Foundation, and the American Psychological Association, released a document outlining some elements of inclusive community that they termed as principles for intergroup projects. While the document uses a lot of “you need to” language, the ten principles it notes that promote intergroup inclusion continue to guide community building activities, even today.

In essence, inclusive communities do the following:

- Recognize that diversity is a valuable asset to the human experience;

- Respect all members, offering equal and full access to resources and opportunity;

- Offer opportunities for all stakeholders to participate in decisions that affect them;

- Expose and respond to events of bigotry and discrimination;

- Detail plans and document work to eliminate discrimination.

This is a long and difficult row to hoe. There are a lot of “isms” still haunting us as a society, and many in our community steadily suckle from them. Those “isms” can seem sexy. They cultivate pride and twist it to mean superiority. They cultivate defensiveness, which creates barriers. And they even cultivate perceptions of inclusion and sensitivity that can turn into social echo chambers. “Isms” are a clever bunch.

It is a difficult problem, one that often seems bluntly intractable. For example, Alphabet, Google’s parent company, spent about $250 million to increase diversity in its workforce to resolve barriers and reduce gender pay gaps. It didn’t work, despite tech workers consistently noting that improving diversity is a major challenge and important to their organizations. That’s a quarter billion dollars to build an inclusive community that failed.

Why? Because welcoming is hard. It is inconvenient. It is not about giving. It is not about hoping. It is not about good or evil. Rather, it is about active engagement in the process of removing barriers so the powerless feel protected.

Our community is struggling, just like Alphabet and many other organizations; and, unfortunately, I am not yet convinced that our outcome will be much different. What I do think is that the majority of the places where we congregate – our festivals, events, and virtual spaces – try to manifest the core elements of inclusive communities. Over time, that praxis will, I hope, overwhelm the binarism, the racism, the heterosexism – all of those isms – one by one.

Am I confident this will happen? No. It certainly will not happen immediately. But the virtue of hospitality that binds practically all Pagan groups will insist that the conversation to welcome strangers will never grow silent.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.