This is part two of a two part series. Click here to read part one.

Transtemporal Care

The Ásatrú practice of blót builds a concept of care in three temporal directions: sideways, backward, and forward. The ritual life of the religion nurtures a sense of both intra- and intergenerational solidarity.

The sideways relationship exists between current practitioners. The small-group kindred structure of American Ásatrú is centered on the concept that members are “kindred by choice,” that they willfully join together in constructed kinship.

This creates a sense of “elective affinities” as practitioners – largely adults and young adults who come to Ásatrú as a consciously chosen religion, rather than an inherited family one – “embrace a sense of kinship… that stem[s] from affinities ‘of mind and soul’” (to use H. Glenn Penny‘s description of the relationship between Germans and Native Americans after 1800).

Poem of the Soul: On the Mountain by Louis Janmot (1854) [public domain]

American practitioners largely come to Ásatrú after being raised in other, usually Christian, religious traditions. The kindred setting empowers them to speak openly about relationships and issues that may be verboten within their own family and familial religious structures.

The membership of Thor’s Oak Kindred includes trans, gay, and adopted individuals, as well as others either estranged from parents or with parents who have never been present in their lives. The kindred setting creates a supportive space in which they can speak more openly than in family situations.

Participants in blót regularly share deeply emotional and private information when they speak during the ancestral portion of the ritual. Doing so serves to build a wider circle of intimate relationships.

This expands the concept of innangarð (“within the yard,” the community with which one feels a strong sense of reciprocal responsibility) beyond merely one’s own original family and opens the individual to a broader concept of care and connection.

The backward temporal relationship is foregrounded during the section of blót focused on the veneration of ancestors. Concepts of ancestry vary greatly, but American practitioners generally take a broad view of who can be honored as an ancestor.

In Thor’s Oak Kindred, the category of ancestor includes deceased family members with whom one has a personal connection (parent, grandparent, aunt, uncle), more distant family relations (such as unknown family members who immigrated to the United States), larger ancestral groups (a particular kin group in Ireland), aspirational ancestors (Germanic tribes of the Roman Era), and those who are kindred by choice (close family friends).

This conception serves to further expand the innangarð of the participants, to broaden the sense of connectedness in ever-expanding temporal and spatial circles. Such a sense is strengthened by the fact that this portion of the blót is more participatory than the hailing of the Powers.

The ritual drinking horn is passed around the circle, and each kindred member speaks like this:

Participant: Women of the Haddock family, I thank you for all the personal sacrifices you made to keep our family strong across the centuries and across the continents. The lives my daughter and I live today would not be possible without your gifts of strength and love. Hail, Haddock women!

Other kindred members: Hail!

Participant drinks from the horn, then pours a draft for the Haddock women into the soil at the base of the tree.

The turn to the ancestors crosses all constructed lines of race, ethnicity, and class.

An African-American Heathen in Thor’s Oak Kindred has hailed Thorhall the Huntsman, a member of Eirik the Red’s crew who sailed to North America around the year 1000. A resolute pagan in the age of Nordic Christian conversion, Thorhall “had paid scant heed to the faith [of Christianity] since it had come to Greenland. Thorhall was not popular with most people.”

As a black man practicing Ásatrú in mostly white and mostly Christian southeast Wisconsin, this kindred member felt a deep kinship with the stubborn pagan who clashed with Eirik’s Christian crew. For this kindred member, an engagement with the lore led to a personal connection with an individual distant in time and place that was subsequently celebrated in the multicultural (African-American, Mexican-American, Guyanese-American, German-American, etc.) and intergenerational (toddler to middle-aged) setting of the group blót.

The expansiveness of this view of ancestry nurtures the ability of practitioners to deeply empathize with the ethnically and spatially “other” people that are often on the front lines of the extreme weather events generated by climate change. The wider the innangarð becomes, the more one feels a sense of connectedness to and responsibility for distant peoples.

The backward temporal relationship leads to a forward one. A.R. Radcliffe-Brown’s analysis of this turn in “primitive society” can also be applied to modern Ásatrú practice:

For in the rites of commemoration of the ancestors it is sufficient that the participants should express their reverential gratitude to those from whom they have received their life, and their sense of duty towards those not yet born, to whom they in due course will stand in the position of revered ancestors. There still remains the sense of dependence. The living depend on those of the past; they have duties to those living in the present and to those of the future who will depend on them.

By regularly focusing on the dependency of the present on the past, Heathens internalize a sense of kinship, literal and symbolic, with a deep past that simultaneously builds a sense of responsibility for the deep future.

Studying a lore that includes rock carvings from approximately 2000 BCE gives modern Heathens a sense of connectedness to an ancient tradition across time; studying scholarship that places Germanic languages in the context of a wider Indo-European “family tree” gives them a sense of connectedness to a cross-cultural network across space. This process of expanding the innangarð moves far beyond what philosopher J. Baird Callicott calls “personal stake in the state of the world” based on relationships of blood.

By foregrounding these connections to a broad and deep past in group ritual, Ásatrú praxis inculcates a sense of connection to a broad and deep future. Practitioners come to see themselves as nodes in a branching network that extends into distant pasts and futures that are equally unknowable.

Theological readings of the lore reinforce this sense of community with both past and future. The Vita Vulframmi on the life of the missionary Wulfram of Sens tells of the pagan Frisian ruler Radbod pulling back on the verge of being baptized. When he asks Wulfram if his forefathers await him in the Christian heaven and is told that, as pagans, they are surely damned, he replies, “I cannot abandon my ancestors and the fellowship of all the greatest men of the Frisian people… I would rather remain in the places that have been reserved for me and all the Frisian nation from time immemorial.” Radbod’s sense of connection to those who came before him overrides any desire for a promised afterlife of heavenly bliss.

Radbod rejects baptism by Wulfram (illustration from Nürnberg, 1693) [Public domain]

Cattle die, kinsmen die, the self dies the same, but the glory of reputation never dies for the one who gets himself a good one.

This suggests a sense that the judgment of future generations on those now living mattered deeply to early pagans. As Radbod’s sense of dependence on past generations overrides desire for individual access to paradise, Odin’s sense of responsibility to future generations trumps desire for the survival of an individual soul.

The contrast between Christian and pagan conceptions of the future is made explicit in the Anglo-Saxon Christian poem The Wanderer, which contains a verse parallel to the one attributed to Odin (the connections are even clearer in the original languages) with a theologically significant change to the punch line:

Here wealth is temporary, here a friend is temporary, here oneself is temporary, here a kinsman is temporary; all this foundation of the earth will become worthless!

Where the focus of the pagan poet is on the time-transcending importance of one’s deeds for future generations, the Christian poet brushes aside all earthly things as “worthless.”

The pagan emphasis on the importance of the deep future’s view of the actions of today’s individuals appears in statements such as the Saga of the Volsungs aside that the hero Sigurð’s “name is known in all tongues north of the Greek Ocean, and so it must remain while the world endures.”

It also appears in the Old Norse doomsday myth of Ragnarök, which includes a postscript about the inhabitants of the far future time cycle after the earth has been renewed following the massive cosmic cataclysm:

Then they will all sit down together and talk and discuss their mysteries and speak of the things that happened in former times, of the Midgard serpent and Fenriswolf. Then they will find in the grass the golden playing pieces that had belonged to the Æsir.

In this melancholy passage, there is an emotional sense of longing (at least for Heathen readers) for a connection with our far distant and unknowable descendants, a hope that they will think of us with kindness and forgive the poor choices we continue to make.

This heartfelt bond with future people also appears in the oath-poem performed as part of the Icelandic Ásatrú ritual of the Landvættablót, as described by Jóhanna G. Harðardóttir of the Ásatrúarfélagið (“Ásatrú Fellowship”):

One special thing we always chant at these blóts is Tryggðamál (“Peace Guarantee Speech,” what Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson calls a medieval Icelandic “ode… about [how] you will keep your word as long as the earth revolves, snow falls, a ship sails, and a Finn skis”) – a very holy and beautiful text.

While fire burns,

Earth is fertile,

A child (which can speak) calls upon its mother

And mother gives birth to her offspring,

Men light fires,

A ship glides,

Shields flash,

Sun shines,

Snow falls,

The Finn skis,

Fir grows,

The falcon flies

On a spring day,

The breeze carries him

Under both wings,

The heavens revolve,

The world is settled,

Wind blows,

Waters fall into the ocean,

Men sow their seeds (of corn).

By including a performance of this text in the blót, the ritual that is dedicated to remembering and thanking the land spirits – and to “reminding us to do our best” – also focuses the attention of the participants on the far future as it simultaneously (via the poetry) celebrates the continuity and connectedness of life across vast stretches of time and (via the oath) emphasizes and sacralizes the responsibility of the present generation to those yet to come.

In addition, the recitation of the text connects human and natural worlds in a tapestry of “the eternal things,” or at least those things hoped to be eternal.

Callicott asks, “Can one really care that in about a million years the human species will, one way or another, become extinct?” Heathen ritual and use of texts suggests that we can, and that we can share and encourage that care with others in our person-to-person communities. The care thus generated and strengthened can be deeply moving in a way that an intellectual commitment to “global human civilization” may not be.

The Web of Wyrd

The above discussion shows that a broad spatial conception accompanies a broad temporal conception in Ásatrú as a lived religion.

Germanic tribes of the Migration Age and Nordic peoples of the Viking Age – two broad categories of people that provide much of the cultural background of modern Ásatrú and Heathenry – are notable for their far-ranging travels, their contacts with many other societies, and their cultural exchange of everything from art styles to religious concepts. The idea of a global village existed long before Marshall McLuhan popularized it.

The tripartite temporal connections in Ásatrú intersect with planet-wide spatial connections through the concept of wyrd, a theological construction built on Old English and Old Norse models. Wyrd encompasses ideas of action and fate, and it centers on the belief that actions taken in the past determine what fate awaits in the future.

The actions of an individual’s ancestors determine what possibilities are open to her, and her own actions modify those possibilities for good or ill; they work on her personal wyrd. Yet her wyrd is also modified by the wyrd of every person with whom she comes into contact – from family, friends, and colleagues to people she meets once on the street. Her wyrd is also affected by the wyrds of all those who interact with the people she herself comes into contact. This complicated branching of causality is known among Heathens as the web of wyrd.

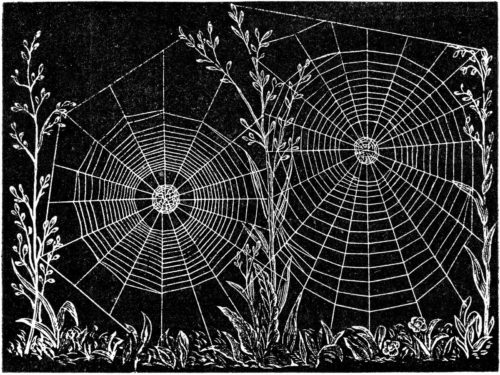

Web of Epeira Strix, an orb-weaving spider (Unknown, 1915) [Public domain]

There is an understanding of the relationship of action and consequence – an understanding that counters Callicott’s claim that the “protracted global scale” of climate change cannot be addressed by moral systems built upon ancient paradigms. By studying ancient lore and reifying its concepts in ritual, practitioners of Ásatrú build an understanding of the interrelatedness of all human actors.

Wyrd is often specifically invoked in blót, as in a Troth “rite of remembrance” that calls upon participants to focus on their connection to mythological, legendary, and historical figures before addressing the Powers directly:

Great Gods

Mighty Goddesses

Alfar [elves] and Disir [female divinities]

Landvaettir of this place

and Wise Etins [giants] in the East;

accept this offering of our mead and our words.

Let them be written into wyrd.

There is a commonly held conception that what is said in blót alters the wyrd of the rite’s participants; one set of instructions for a blót to the sea goddess Rán reminds practitioners that “[w]ords spoken like this echo into the Well of Wyrd [like the web, a common metaphor connected to wyrd], so people should use care in their word choice, be respectful, only make oaths one intends to keep, etc.”

One year ago, President Donald Trump announced that the United States will withdraw from the Paris Agreement on climate change. The Heathen ideal of choosing words carefully, acting in a respectful manner, and keeping one’s oaths seems very attractive today.

A Heathen Response to Climate Change

In 2015, Diana Paxson presented a talk on “a Heathen response to climate change” at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Salt Lake City. She is a past Steerswoman of the Troth and currently serves as Clergy Coordinator and editor of the organization’s quarterly journal, Idunna.

In her presentation, she addresses myths of Odin in which the god travels the world, gathering information about the future from ancient giants and the magically reanimated corpses of dead prophetesses, and makes preparations for the coming cataclysm of Ragnarök. She connects these myths to climate change and to the growth of the Ásatrú religion since the early 1970s:

The world has recovered from some horrendous natural disasters in the past. But they occur one at a time, in widely spaced locations, not simultaneously all over the globe. What if the reason that Odin has been getting in touch with so many people in recent years is because humans now have the power to unbalance the ecosystem beyond its ability to restore equilibrium, and he’s trying to get us to stop? I think that the only thing that could make such a disaster worse would be the realization that we brought it on ourselves.

Of course, that realization is exactly the one staring us all in the face. Paxson goes on to state that Odin

is a god of consciousness, and a change in consciousness is what is needed now. He is a god of communication and magic. To make the changes that will save us we need to use those mind-bending skills not for evil, but for good.

Ásatrú lore provides guidelines and examplars, not rules or commandments. These models can suggest new ways of thinking about and relating to climate change. As Paxson points out, “a god of consciousness” can be a useful concept in dealing with current challenges, whether one believes in his literal existence or not.

Odin between the fires (Willy Pogany, 1920) [Public domain]

Despite coming from a minority, marginalized, and misunderstood religion, these ways of engaging in a ritual context with issues of climate change ethics can provide possible paths forward for members of other faith traditions. In particular, religious leaders who are seeking innovative ways to engage their communities with environmental issues may find some inspiration for their own ministerial work while changing and adapting the specific elements to fit the theology and praxis of their respective religions.

In the field of ethics, I hope that this column will open a space in the discussion of climate change for practitioners of Ásatrú to inhabit. Willis Jenkins begins his introduction to The Future of Ethics by writing that “[e]thics seems imperiled by unprecedented problems.” If this is so, any voice with something new and meaningful to say regarding the critical problems of climate change should be made welcome.

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.