TWH — Writer Kat Kimbriel was 16 years old when she read the first three Earthsea novels by Ursula K. Le Guin, the acclaimed science fiction/fantasy writer who died Jan. 22 at the age of 88, and who long ago had become an inadvertent teacher for many Pagans.

“I was still a Christian — saw only one path to the divine — but was already questioning that lesson,” Kimbriel said. “With Earthsea, I suddenly saw, through Le Guin’s anthropological roots and Taoist beliefs, peoples of her archipelago that were radically different in culture, history, beliefs, faith. It was a revelation . . . . Something shifted subconsciously. After that point, I no longer felt threatened at the idea that my faith might not be the one, true way.”

After college, Kimbriel embarked on her own path as a SF/fantasy writer, and her encounter with Le Guin’s The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction further changed her life.

“I learned my writing was not there to preach to the converted,” said Kimbriel, author of the Night Calls and Chronicles of Nuala series under the name Katharine Eliska Kimbriel.

“At that point, I understood that the Christ had lessons and compassion to spare, but I had little use for the religion that grew from and left behind his words. That was when I started studying the great religions, including basic Witchcraft. First it would end up in my novels, and then it would end up in a quiet corner of my home.”

Kimbriel, who describes her spiritual path as “eclectic,” is not alone in the Pagan community. While Le Guin was not a Pagan herself, she embraced Taoism and even published her own translation of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching, and a number of Pagans esteem her, through her writings, as a teacher and mentor.

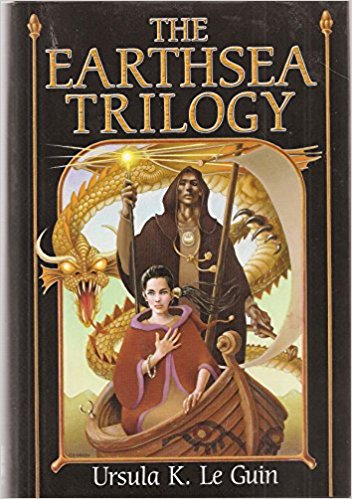

“Pagans often mention Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea series of novels as a teaching tool for the ethical use of magic,” writes Barbara Jane Davy in her 2006 book Introduction to Pagan Studies.

In a discussion of the Wiccan Rede, Davy notes that the Earthsea series, which Le Guin expanded to six books from its original trilogy, “illustrates the ethics of magic use, and is often recommended as a teaching tool. In A Wizard of Earthsea, the protagonist, out of pride in response to the taunting of a schoolmate, casts a spell to summon the spirit of a dead woman and accidentally looses a malevolent entity that haunts him for many years.”

Graham Harvey, in his 2011 book Contemporary Paganism: Religions of the Earth from Druids and Witches to Heathens and Ecofeminists (2nd Edition), says the “powerfully compelling” Earthsea books provide “a rich narrative framework to an ethical context for magic.”

The novels, Harvey adds, “Explore themes of importance to Pagans, especially to those who engage in magic. They inculcate responsible use of power, rather than purely self-centered motivations, and reinforce the idea that, far from being destructive, fears faced and darkness explored can lead to considerable personal growth. Le Guin’s writings are more holistic than Tolkien’s, and explore more radical social and personal alternatives to contemporary life. Issues of gender and sexuality are an important part of her writing; it is telling that there are more significant women in Le Guin’s works than in Tolkien’s.”

Ursula K. Le Guin [Eileen Gunn]

Katherine Lampe, author of the Caitlin Ross series, which details the adventures of a witch in rural Colorado, goes deeper into Earthsea in her blog post “10 Novels that Informed my Paganism: “Earthsea had everything — magic, a school for wizards, dragons, and numerous quests. It hooked me from the first page.

“From the very beginning, the trilogy serves up a substantial helping of philosophy along with its engaging plot. The magical system is all about balance . . . . The wizards can’t simply do anything they like. Taking energy from one place removes it from another, and every act has consequences. The protagonist learns this to his sorrow when he works a spell out of ego and unleashes a horror. This was my first introduction to the concepts of Karma and the Shadow Self, as well as the idea that sometimes the better part of wisdom for people of power lies in acceptance rather than action.”

Novelist Lev Grossman, author of the bestselling Magicians trilogy, which was made into a series of the same name on the Syfy channel that is now in its third season, places Le Guin’s Earthsea in a larger context.

“A Wizard of Earthsea . . . was published in 1968 and it was a revelation for fantasy readers, and possibly a revolution,” Grossman said in an interview about his favorite fantasy works.

“In Le Guin’s work you can see a predominantly Christian, patriarchal, English tradition reinvented by a writer who was not only an American woman but a Taoist-atheist . . . . Both Tolkien and Lewis were devout Christians, but Le Guin brought fantasy back to its pagan roots. She used as the foundations of her magic system and her story the building blocks of nature and sex and language.”

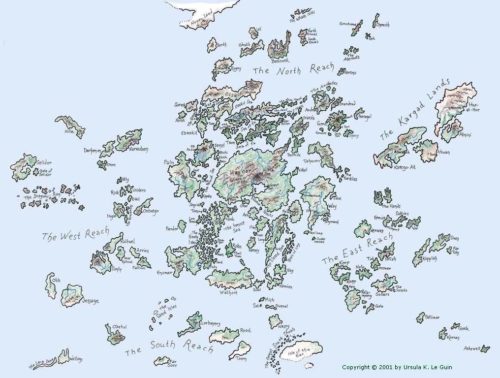

Earthsea map drawn by Ursula K. Le Guin

What did Le Guin herself have to say about Paganism? Not much, if a perusal of her website and a Google search can be said to be indicative. However, Le Guin’s own website, ursulakleguin.com, includes a de facto “exchange,” of sorts, between the creator of an Earthsea television miniseries and the late grand dame of fantasy and sci-fi.

The Le Guin website reproduces this passage from the December 2004 issue of Sci Fi Magazine:

“Miss Le Guin was not involved in the development of the material or the making of the film, but we’ve been very, very honest to the books,” explains director Rob Lieberman.

“We’ve tried to capture all the levels of spiritualism, emotional content and metaphorical messages. Throughout the whole piece, I saw it as having a great duality of spirituality versus paganism and wizardry, male and female duality. The final moments of the film culminate in the union of all that and represent two different belief systems in this world, and that’s what Ursula intended to make a statement about. The only thing that saves this Earthsea universe is the union of those two beliefs.”

In a tart reply dated Nov. 13, 2004, Le Guin wrote: “I was not included in planning [the miniseries] and was given no part in discussions or decisions. That makes it particularly galling of the director to put words in my mouth.” She continued on:

Mr. Lieberman has every right to say what his intentions were in making the film he directed, called Earthsea. He has no right at all to state what I intended in writing the Earthsea books . . . So, for the record: there is no statement in the books, nor did I ever intend to make a statement, about ‘the union of two belief systems.’ There’s nothing at all about the ‘duality of spirituality and paganism,’ whatever that means, either.

Earlier in the article, Robert Halmi is quoted as saying that Earthsea ‘has people who believe and people who do not believe.’ I can only admire Mr. Halmi’s imagination, but I wish he’d left mine alone.

In the books, the wizardry of the Archipelago and the ritualism of the Kargs are opposed and united, like the yang and yin. The rejoining of the broken arm-ring is a symbol of the restoration of an unresting, active balance, offering a risky chance of peace.

This has absolutely nothing to do with ‘people who believe and people who do not believe.’ That terrible division into Believers and Unbelievers (itself a matter not of reason but of belief) is one which bedevils Christianity and Islam and drives their wars. But the wizards of Earthsea would look on such wars as madness, and the dragons of Earthsea would laugh at them and fly away . . . Toto, something tells me Earthsea isn’t Iraq.”

Kat Kimbriel [Brenda Ladd]

Kimbriel added: “Le Guin, and Earthsea are the real thing. I have no doubt she has returned to the stars and dances as a celestial dragon.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.