![]()

At the beginning of this semester, students in my undergraduate college course on Grimms’ Fairy Tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen) read the prefaces to the two volumes of the first edition. In the preface to the second volume of 1815, Wilhelm Grimm responds to criticism of the first volume of 1812 after asserting that the collection of tales should serve as an “educational primer” (Erziehungsbuch):

Objections have been raised against this last point because this or that might be embarrassing and would be unsuitable for children or offensive (when the tales might touch on certain situations and relations – even the mentioning of the bad things the devil does) and that parents might not want to put the book into the hands of children. That concern might be legitimate in certain cases, and then one can easily make selections. On the whole it is certainly not necessary.

This argument is often heard today. Even while receiving credit for the positive results of their labors, authors and producers of narrative works are absolved of blame for negative consequences. If the book is considered to have beneficial aspects, the creator is congratulated for creating an important work. If the same text is seen as problematic, well, that’s really just the opinion of people who choose to interpret it that way. In the particular case of books read by children, all responsibility rests with the parents and none with the producer, so the argument goes.

A portrait of Wilhelm Grimm [public domain].

Nature itself provides our best evidence, for it has allowed these and those flowers and leaves to grow into their own colors and shapes. If they are not beneficial for any person or personal needs, something that the flowers and leaves are unaware of, then that person can walk right by them, but the individual cannot demand that they be colored and cut according to his or her needs. Or, in other words, rain and dew provide a benefit for everything on earth. Whoever is afraid to put plants outside because they might be too delicate and could be harmed and would rather water them inside cannot demand to put an end to the rain and dew. Everything that is natural can also become beneficial. And that is what our aim should be.

This line of argument also lives on in modern discussions. By making the claim of naturalness, the producer of the work is again absolved of responsibility for anything in his work not seen as positive, and the reader who objects is associated with overly delicate flowers – the clear Romantic-era equivalent of today’s overused “snowflake” putdown, with the same connotations of gross weakness.

Perhaps most striking is Grimm’s forwarding of an assertion often made by conservatives and libertarians today: the claim that any who question or frame as a problem the social effects of narrative works are calling for forceful censorship. Then and now, dialogue is stifled when those calling for reflection are misrepresented in the form of Bradburian firemen out to burn anything deemed offensive to overly tender sensibilities.

Grimm concludes this section of his preface with a strong statement:

Incidentally, we are not aware of a single salutary and powerful book that has edified the people in which such dubious matters don’t appear to a great extent, even if we place the Bible at the top of the list. Making the right use of a book doesn’t result in finding evil, but rather, as an appealing saying puts it, evidence of our hearts. Children read the stars without fear, while others, according to folk belief, insult angels by doing this.

This passage, elegant even in translation, highlights issues that continue to be part of private and public dialogue today. Is an author responsible for how her creation is received and used after publication? How do we understand the role of the producer when the same work is viewed extremely positively and incredibly negatively by different communities? What does reaction to a text say about the reader? How does reaction to a work reflect a society’s values? How does a society determine what is appropriate, both for children and for public space in general?

Two well-known cases illustrate the highly fraught nature of these questions.

The Woman in the Refrigerator

Back in 1994, issue number 54 of DC’s Green Lantern comic book series featured a host of visual tropes common to 1990s comic book titillation for boys: a woman in underpants and lace gloves looks over her shoulder and offers a sexual invitation, a woman takes a shower with strategic blurring, and a woman gets beaten and strangled. The come-hither look and the strangulation images are presented from the perspective of the male character. Nine pages after offering the invitation to intercourse and six pages after the shower scene, the woman lies dead on the kitchen floor. The woman in question is Alexandra DeWitt, who had been introduced to readers only six issues earlier. She was first presented in the last panel of Green Lantern 48, without being named and wearing a bikini with a top in the process of falling off.

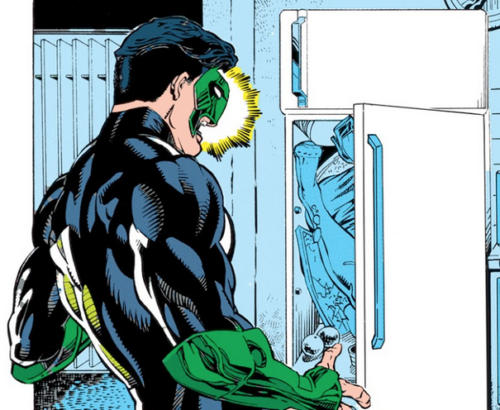

After DeWitt’s death, Kyle Rayner (then the protagonist of the series) returns home, saying out loud to himself that his girlfriend “better be ready” for the promised sexy surprise made when he flew off to “do something heroic” as Green Lantern. He finds her corpse stuffed into the refrigerator by her murderer, the evil Major Force. After the villain sticks out his hand and says that he wants to take the hero’s ring of power, Rayner attacks him in silent rage for four full pages before darkly declaring, “You’re dead! I’m going to kill you now.” At that point, his power ring futzes out and he laments his impotence as the enormous purple-headed Force rises up behind his backside, and the issue ends.

Part of the infamous refrigerator panel [DC Comics].

The sexualization of the violence in this story is remarkable in its obviousness. The male reader — for the intended audience is clearly young men — is invited to see the female character from the perspective of both the male sexual partner and the male murderer. The images come so close together that there is a blurring of the sexual and violent acts. The humiliation of Rayner by Major Force is itself clearly sexualized; the villain first thwarts his expected intercourse by killing his girlfriend, then claims possession of the source of Rayner’s strength, then revels in the failure of Ryaner to finish him off when his power ring goes limp, so to speak. The final image of a pained and sweaty Rayner about to be attacked from the rear by the raised fist of the grimacing villain is a bookend to the first image of the issue, which shows Rayner grinning and possessively carrying DeWitt as he flies through the air. When she asks him to “slow down, for heaven’s sake,” he tells her that she’s actually “lovin’ it.” The title of the story fits both the first and last illustration of the issue: “Forced Entry.”

What does this all have to do with Grimm? As mentioned above, this particular issue often comes up in discussions about images of women in comic books particularly and mainstream entertainment in general. When I’ve brought this story up in discussions about media representations of women, I’ve received incredibly belligerent pushback from comics readers of the straight, white, male and/or Heathen persuasion. No matter what the initial point is, the regular responses are (1) “if you don’t like it, don’t read it,” (2) “rape and murder happen in the real world, so they should happen in fiction,” (3) “I grew up reading stuff like this, and I’m totally fine,” and (4) “this is censorship, and I have a First Amendment right to read whatever I want.” Aside from the difference in tone, these assertions generally correspond to the arguments made by Wilhelm Grimm in his 1815 preface.

We must remember Grimm’s conclusion, and ask the questions about reader reactions to stories and what the stories we choose to consume say about our society. What is so attractive about this idea of a woman’s brutalization being used to motivate a man to commit acts of extreme violence? Why do male writers repeatedly tell this same tale in endless formulations, and why do male readers repeatedly pay to watch this story unfold? Wendy Doniger is fond of citing the idea of Claude Lévi-Strauss that repetition of mythic narratives suggests that there is something in the core of the tale that is deeply problematic to the society that tells it, that there is something being struggled with that can’t find easy resolution. Is that what is happening here? Are men troubled by the conflation of their attraction to the female body and their attraction to extreme violence?

Is this more about a confusion of sex and violence, an inability to separate the two? There are almost twice as many pages in the Green Lantern issue dedicated to the physical fight between the two men as there are to the flirting between Rayner and DeWitt. The heterosexual story elements are prelude to the central conflict between the two men. The intensity of the relationship between the opposing male characters — with a higher page count and stronger emotions than that between the male and female characters — is reminiscent of the Hindu concept of dvesha-bhakti, the devotion of hatred in which someone focuses so intensely and obsessively on their enemy that they are bound with the power of an inverted love. Given the story’s title and the final image of Rayner’s impotence, it’s telling that the cover — meant to attract the young man browsing the shelves back in the mid-1990s comic shop — is Kyle holding a ridiculously oversized green gun and emptying his load onto the chest of his muscular opponent, whose coloring makes him appear nude. Maybe the issues in the issue have more to do with Ace and Gary than with Rayner and DeWitt.

What does the corporate production and commercial consumption of tales of the “women in the refrigerator” type say about American society? The stories of a society show the concerns of a society, and corporate entertainment is just as deeply woven into everyday life in the United States today as folktales were in European society centuries ago. Wilhelm Grimm (and many who followed him) insisted on the fairy tales as education, despite the fact that most of the tale had no claim to such function before being assembled together by the Grimms. The cauldron of stories doesn’t only shape the youngest children; young men are educated and socialized via the entertainment they consume, no matter what the intention of the producers may have been.

What is the result of generations of American men being raised with stories of women who exist only in relation to violent male protagonists, and whose violations and murders are meaningful only as they drive his story forward? In the Grimms’ day, there was a willingness to openly discuss the ways in which the stories told both reflected and shaped the society of which they were a part. Have we lost the ability to discuss these issues in regards to the tales of our own times without turning each other into straw men?

The Girl with Two Mothers

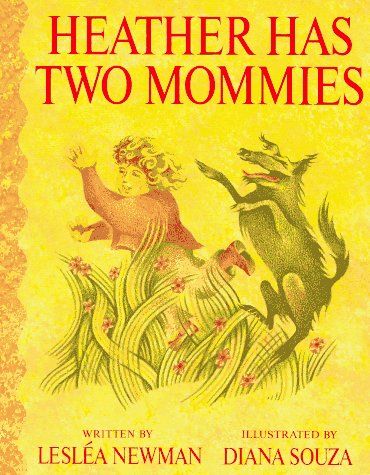

In 1989, Alyson Books published Lesléa Newman’s Heather Has Two Mommies, with illustrations by Diana Souza. The book was meant for three- to eight-year-old children and told the story of a little girl who takes if for granted that things in her life come in pairs: arms, eyes, legs, pets, and mommies. Newman wrote the book when a lesbian parent remarked to her that there were no books to read her new child “that show our type of family.” In response, Newman created a story that deals with a young girls’s experience of discovering that her family is different from those of her classmates, and explains how the process of artificial insemination led to her birth.

Newsweek reported in 1991 that the book provided “a message gay parents are yearning for.” Newman herself says that the reactions she received were “mostly gratitude from lesbian moms.” As one of the first popular texts of its type, the book found a welcoming audience among those who had longed for a book to share with their children that reflected their own family structures. However, as awareness of the book spread beyond this target audience and into the general public, the text quickly became a lightning rod for the religious right in the culture wars of the 1990s.

The 1989 edition of Heather Has Two Mommies [Alyson Books].

For the 10th anniversary edition, published in 2000, the artificial insemination material was removed from the book, either to make the text “more accessible to younger children” or in deference to the controversy that had followed the book for a decade. After the 20th anniversary edition was published, the text was challenged by a a queer Muslim scholar for promoting a white, monogamous, upper-middle-class image of LGBTQ families. By the redesigned 2015 edition, any angst in the story had been evened out, other “nontraditional” families were included, and “validation [was] the order of the day.” The later incarnations of the 1989 text had been shaped by pressure from both sides of the culture wars over identity and family in the U.S.

The old arguments over this children’s book popped into my head during class when I was discussing Wilhelm Grimm’s preface and how I felt it related to the arguments over violence against women in modern American entertainment. If progressives can argue that the tales we consume as children and as adults shape us as individuals and as a society, and therefore we should all be concerned about the dissemination of texts that portray women in what they see as a morally problematic fashion, why can’t conservatives argue the same thing about texts that portray families in a way that they see as morally problematic? As with much in our public discourse, the side that argues for the positive nature of one of these types of texts usually argues against the other type. As Heather knew, many things come in pairs.

On one hand, progressives argue that “women in refrigerators” stories promote morally abhorrent sexual violence and discrimination against women, while books like Heather Has Two Mommies promote tolerance and understanding within a multicultural society. On the other hand, conservatives argue that adults have the constitutional right to read whatever they want and that the government (in the form of public schools) shouldn’t force children to accept lifestyles that their parents find morally abhorrent.

As a society, we do regulate what kinds of entertainment adults can consume. Child pornography and snuff films have been banned, censored, and criminalized. We have also decided on a graded system based on age for film viewing, even though the MPAA ratings seem to have lost any enforceability even as they evince an overly liberal stance toward extreme violence and an overly conservative stance toward language and nudity. At least there remains some sense in American society that there are things which are unsuitable for younger children, even if we can’t agree on what those things are. For adult audiences, the Cartmanesque “I do what I want” attitude continues to dominate, encouraged as it is by the corporate entertainment industry that will cross any boundary for buzz and dollars.

Are the arguments against “women in refrigerators” and against Heather Has Two Mommies equally valid? Even while trying to remain sensitive to the perspectives of both sides, they clearly are not. Questioning whether we should support commercial entertainment that promotes sexual and sexualized violence is not censorship. Calling upon specific elements of the entertainment industry to do better is not infringing anyone’s First Amendment rights. However, demanding that public schools ban books that education professionals have determined to be beneficial for fostering understanding and good citizenship in the modern age because of one’s personal animus against people of an orientation, identity, race, or religion you are prejudiced against does indeed attack the rights of students to the best education they can have, and it insists that public schools make the same censorship choices as private religious schools.

These are methods, and one can of course find examples of progressives who want a book removed from the schools and of conservatives who stage corporate boycotts. The core issues remain unresolved. To return once more to issues raised by reading Wilhelm Grimm, the question at the heart of the matter is this: whether we are discussing children’s books or corporate entertainment, if we believe that the tales told both shape and reflect their parent society, what do we want our stories to say about us?

How do we want to present ourselves to our children? Do we want to look into their eyes and tell them to accept those whose lives are different from our own, or do we want to tell them we can’t even tell stories about “those people” because they would be corrupted in the very telling of the tale? As adults, how do we want to live our lives? Do we want to spend any non-work hours we manage to save up staring at images of raped and murdered women for entertainment? Are the real-world consequences of these obsessions in actual acts of violence against women worth the hours of private titillation?

I’m not telling people how to live their individual lives. I’m asking how we can lift up our society together in a way that respects difference even when it conflicts with our own beliefs. I believe in the power of story, and I believe that we can do better by our children and by ourselves than we currently are. Let’s write the stories of our age in a way that avoids the tragedies of the past.

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.