![]()

If you were to arrive at Iceland’s Keflavik International Airport during the month of December expecting cheerful holiday lights or a jolly fat man in a red suit, you would be in for a bit of a surprise. Instead of being welcomed into the country by the familiar and cheerful figure of Santa Claus, your first encounter would be with slightly menacing, unmistakably witch-like figure: Gryla.

Gryla [T. Titus].

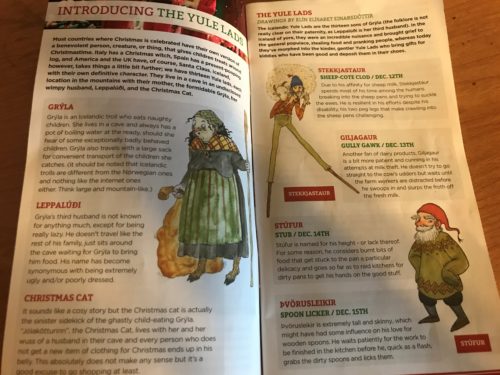

From stockings full of coal to receiving a whipping to the clutches of Krampus, legends of harmful consequences for bad children are quite common during the holiday season, yet that is not why Gryla the troll has become associated with the Icelandic holidays. Terry Gunnell of the University of Reykjavik dates the legends of Gryla to at least the 13th century, when the ogress was not associated with Christmas. However, as the legend evolved and made its way to the 1600s, Gryla became more and more associated with the December holiday, partially because of her adopted children: the 13 Yule Lads.

The 13 bearded Yule Lads have taken a central role in modern Icelandic holiday celebrations. In the 13 days before Dec. 25, the lads are said to descend from the mountains one by one. They each enter a village on their appointed evening, and bring their own personal kind of mischief with them. In modern celebrations, children leave out shoes for the lads on each of the 13 nights. If a child has been good, they receive a gift. If they have been bad, they receive a rotten potato, thus they have been referred to as Iceland’s 13 Santa Clauses. The Yule Lads have become beloved cultural figures and part of the local tourist industry. In downtown Reykjavik, cheerful animated images of the lads are projected onto buildings to create a decidedly local holiday season feeling to the city.

[T.Titus.]

The 13 Yule Lads

- Sheep-Cote Clod (AKA Stiffy Legs) – Dec. 12: This peg-legged lad sneaks into sheep pens and sucks the milk out of a family’s ewes.

- Gully Gawk – Dec. 13: Gully Gawk loves milk too, but he steals the foam off of buckets of fresh milk.

- Stubby – Dec. 14: The shortest Yule Lad, Stubby breaks into a family’s kitchen to lick the burned bits of food off of their pots and pans.

- Spoon Licker – Dec. 15: As his name implies, this scrawny lad sneaks into kitchen after dinner is over and licks all of the family’s spoons.

- Pot Licker – Dec.r 16: Pot Licker is more aggressive than his spoon-loving brother. He knocks at the front door, then takes advantage of the household distraction to sneak in and help himself to the pots in the kitchen.

- Bowl Licker – Dec. 17: This lad’s greatest desire is to steal your bowl of food.

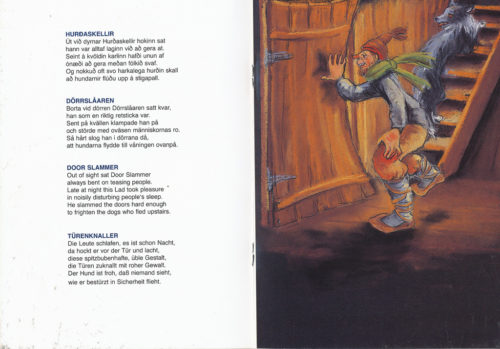

- Door Slammer – Dec. 18: He waits until the town is asleep, then runs around slamming doors for fun.

- Skyr Gobbler – Dec. 19: Iceland has its own form of yogurt, which they call skyr. Skyr Gobbler is quite partial to it and enjoys stealing it from others.

- Sausage Swiper – Dec. 20: Also a food-stealing lad, this one will take all your sausage.

- Window Peeper – Dec. 21: He sneaks around at night looking for open windows to gaze into.

- Door Sniffer – Dec. 22: Always in search of bread, Door Sniffer uses his large nose to find it inside homes.

- Meat Hook – Dec. 23: In his search for meat, this lad sends his long hook down chimneys to steal what he wants.

- Candle Beggar – Dec. 24: December is quite dark in Iceland, and this lad makes it worse by stealing precious candles.

Belief in the hidden people, nature spirits, elves, and other mythological creatures is quite common in Iceland. This could be the origin of these somewhat frightening holiday spirits. Magnús Skarphéðinsson, an elf researcher in Iceland, says that the “Yule Lads are like the hidden people” and live in a different, but adjacent, dimension than ours. Gunnell draws a distinction between nature spirits and the Norse concept of elves, but he says that with mingling of cultures, these differences became blurry, leading to locals’ belief in the Hidden People.

Door Slammer [Flickr].

Gunnell goes further in his multicultural explanation of the Yule Lads’ origins. He notes that it is common in Scandinavia for young men to run around from farm to farm wearing “a sort of a goat costume.” Thus, says Gunnell, “It may well be that the Yule Lads were at one time just a bunch of young men who would visit nearby farms in costumes and masks—pretending they were supernatural spirits that had come down from the mountain.”

That mundane origin could easily fold into preexisting beliefs in nature spirits. Gunnell goes on to say that in Norway, it is believed that nature spirits begin to come down from the mountain in October, slowly taking over the land and forcing the people into their homes as the darkness got thicker. In December, everyone stayed inside for fear of the land spirits just outside their doors. “It’s really all about nature spirits taking back their land,” he says. Norway and its former colony Iceland indeed share many common ties, and this could be another one.

Gunnell’s ideas of cultural crossbreeding and supernatural beliefs also bring us back to the witch-like troll figure of Gryla, mother of the 13 lads. He states that the name Gryla is similar to a Danish word for “Growler,” which, he explains, is a word commonly used to refer to trolls or giants. “Their names,” he says, “come from the sounds you hear on the landscape from animals.” Danish rule over the island began in 1380. Denmark’s influence would have begun before that, roughly to the time to which Gunnell dates Gryla’s origins.

Much like December in Iceland, Gryla and her 13 sons are dark and menacing. They appear as the dark gets longer, the days get greyer, and the cold gets deeper. They disappear as the sun begins to return. With modern technology, the dark and cold have become easier to live with, and in the last hundred years the Yule Lads have evolved a more cheerful demeanor. For the Pagan, the intriguing Yule Lad mythology may hold a similar spiritual truth to the wheel of the year. In December, the time of rapidly advancing darkness and cold, the world seems to become a more dangerous place. At Yule, the light is reborn and the danger slowly recedes. The Yule Lads, appearing one day at a time before Dec. 25 and departing a day at a time afterward, may be another mythological story that coincides with natural cycles. Seen from the Pagan point of view, they are another example of how myth reveals the spirits and sacredness of the natural world.

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.