![]()

Steampunk is awesome (/squee!). If you have never visited one of the major events, I highly recommend adding them to your list of coolness to be experienced. The steampunk cons are carefully imagined, orchestrated and implemented. The participants approach their costuming with amazing dedication, and the mechanical props created are dazzling; they are also often useless, but that’s not the point. The point is the remarkable enthusiasm within the subculture to manifest a temporary world that speaks to them for a weekend at a time. The cons take tremendous effort, and are nothing less than will manifested in the present.

The requisite goggles [S. Ciott].

Both can trace their origins to late-Victorian counter-culture.

The precursors of modern Paganism center on Enlightenment libertines too numerous to mention by name, but ranging from Blavatsky to Crowley to Gurdiejeff. As a group they sought justification for their anti-Christian stance in the abundant pre-Christian wisdom of Europe. These mystics created secret teachings and magical practices that slowly built an esoteric movement that was both popular and private at the same time. Add to that the challenge and expansion of religious freedom, new advances in science and “pre-Adamism,” the articulation of magical theories of sex, an increasingly powerful conversation on gender and racial equality, and we begin to recognize many of the elements that frame and ultimately coalesce into modern Paganism.

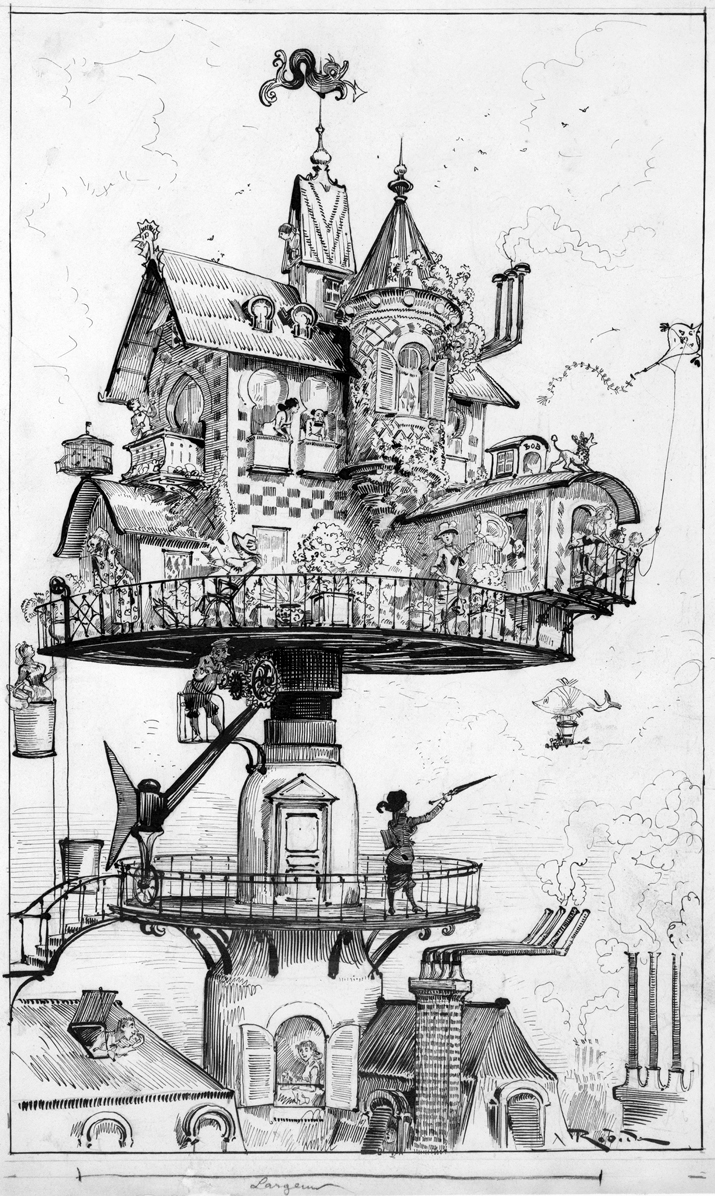

Likewise, the forerunners of the modern steampunk movement are deeply rooted in the scientific romances of authors like Mary Shelley, H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, and the art of Albert Robida. Those romances imagine a world where science offered new answers and challenged the spirit. They introduced new ethical awakenings about how science can define the world and the roles of humans as active shapers of reality. Steampunk, as a genre, even acknowledges its undesirable origins in Victorian colonial oppression and white centrism, and openly struggles against them.

Like Neopaganism but more recently, steampunk has reverberated in the cultural landscape. Like all movements, there Is wax and wane of interest. Core adherents are still present, but the king tides of newcomers are now further apart. There is still interest, but it is more measured. In part, this has happened because of steampunk’s own success. There was a brief period of time when the genre captivated pop culture and while now more reserved, it is much more a household term than a few years ago. Steampunk’s prevalence subverted its eccentricity.

Maison tournante aérienne (1883) by Robida [public domain].

Whether from a continuing loss of individuality from social media to the Black Friday buying frenzy of unnecessary goods vomited from an impersonal assembly line, steampunk is a counterbalance. Steampunk remains conscious of class and power while remaining centered on making and on being. The answer to, “why does steampunk exist?” is the question, “why must the world look like it does?” Steampunk will not perish into obscurity because it speaks to our contemporary world’s failing as clearly as the smartphone acts as its symbol.

All movements struggle with the reality — as Yeats warned in The Second Coming — that things fall apart. But what steampunk is telling us as a movement is that the longevity of any campaign, religious or secular, is intimately tied to how the movement speaks to the moment. Look at Christianity. Yes, the rise of Christianity was inextricably tied to the rising oppression of the Roman state and European aristocratic power, but Christians also did the unthinkable: they cared for the poor. Yes, there were bad Christian leaders all power-hungry and evil, but on balance Christianity worked on the very practical matter of lessening suffering and uplifting the poor. Let’s put aside any romance on this, life in Europe for the average person from the decline of the Roman Empire to the mid-nineteenth century sucked. It was foul, not to mention that paper cuts could kill you; that is, if you survived smallpox, or plague, or apoplexy (yeah me either, who knew people died from that?).

Some of our European ancestors may have converted to Christianity from coercion, but more likely they did so for practical reasons. If the abbey is sharing its food, that’s a very practical reason listening to what they have to say. If the abbey can help us alleviate a little of the unrelenting death and suffering around us, they might be worth a listen. Finally, they converted if for nothing else than for fitting in and having something to do with friends and family on Sunday.

Sure, it changed later because of obligation, but the tide of conversion was far slower than many think; and the ordinary aspect of “converting” was just very pragmatic. Our ancestors were as practical as we are today. They were being offered a spiritual path that informed their moment, their condition and their understanding of the world. The faith they were offered informed them about how to live, how to understand their lives and how to understand their deaths. They were looking for ways to stop things from falling apart; and Christianity offered them some glue.

I think one of the challenges of modern Paganism is to forcefully and eloquently speak to the modern condition. We should be able to do so, acknowledging how we are collectively the product of modernity. The romance of a blissful Pagan past is seductive and sweetly nostalgic. “Can it be that it was all so simple then? Or has time rewritten every line?” No, and yes. That idyllic past is fictional. An idyllic Neopagan future, however, is both attainable and practical; provided we resist that falling apart One thing is always true: the future is easier to shape than the past.

We have access to ancient texts like the eddas and works of Roman Pagans. Tather than looking to them solely for reconstruction, we can use them understand life in the Anthropocene epoch. We can understand the world as immanent and nature as informative. We can communicate our role in the world and our responsibility as both citizens of a human society and products of a natural, evolving planetary system experiencing climate change. As a modern set of collective paths, we can be fluent in the power of science, the requirements of empiricism and the reality of evidence as much as we can be fluent in the spiritual strength of magic and ritual. We can do so through ancient traditions while recognizing that our paths were born in the modern age, with equal command of science and spirituality.

Like other faiths, I think we can answer the call of the present. We can respond to the question, “why does Paganism still exist?” not as a counter-culture; but with a clear question of our own, “why do you live the way you do?” Through that question, let modern Paganism speak to the modern condition. We are each responsible for that advocacy speaking about how our Paganism informs us about living in this time and place. Otherwise, there is not much to gain from its practice; even less to gain from its study, until eventually, things fall apart.

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.