UNITED STATES –Despite oil prices hovering some $80 a barrel below all-time highs, the push to build new pipelines to bring petroleum to refineries, and then to market continues to make headlines. Most every major pipeline proposed in recent years has been met with some level of resistance by environmentalists, on the ground or in the courts.

Two Pagans, each of whom has been engaged on one of those fronts, spoke about what they’re fighting for and the challenges faced in opposing oil pipelines.

Installed Keystone Pipeline [Photo Credit: Public Citizen / Flickr, CC lic.]

That local case took on renewed urgency when President Trump cleared the way for the pipeline to be built. Pipeline owner TransCanada’s legal team succeeded in convincing regulatory authorities that all the conditions imposed on granting the permit in 2010 were still being complied with, and this determination was upheld by a lower court.

Now, that court decision is being appealed.

In South Dakota, agricultural and indigenous interests are aligned. Martinez represents Dakota Rural Action in a case that also includes four Sioux tribes. While he’s not licensed in Nebraska, he is also advising attorneys in that state, where a new route for the Keystone XL was recently approved.

That approval “is a lot more complicated for TransCanada,” Martinez said. Regulators in Nebraska did provide a path, but not the one being sought. In a 3-2 vote, a longer route, which is farther to the east than the proposed one, was authorized by Nebraska Public Service Commission members.

“Now, they have to negotiate easements with a new set of landowners,” and if some of them don’t agree, pursue eminent domain in the courts.

“I can’t imagine [landowners] will be too keen on that, considering the spill from Keystone 1 in South Dakota,” Martinez said. “It’s starting to sink in that land can be at risk.”

Should some withhold permission, the question becomes whether eminent domain can be used to benefit a private project.

Another possible issue with the new route is whether or not it will entail a new environmental impact statement. TransCanada attorneys will likely push to simply update the old one, but that’s likely to be opposed under the National Environmental Policy Act, he said.

In South Dakota, Martinez and others are arguing that the permit was extended without a thorough review. They also want regulators to be held to the standard of upholding the public trust, under which natural resources are considered jointly owned by members of the public. In the past it’s been applied to parks, and this would be a novel interpretation of the doctrine.

Martinez said in 2015, “One thing I never want to lose sight of is that this is a life or death matter for them. . . . They’re the ones that would bear the brunt if something were to go wrong. That’s the physical nature of pipeline slicing through those states, and what might happen to water resources in that region in the event of a breach.”

Today, he says his clients are prepared for a long fight, and will never accede to that slicing and dicing of their lands. Pipelines pose far too much danger to land and water to allow more of them to be built. However, “I’ve got a lot of trepidation, with the current administration trying to criminalize dissent.”

“If [Keystone XL] does get built, you’ll see protests mobilize across South Dakota and Nebraska in opposition, Martinez speculates.

“People are still trying to digest the lessons from dealing the DAPL,” the Dakota Access Pipeline.

It’s in the wake of those protests, centered at Standing Rock, that state lawmakers first started trying to limit those rights; Martinez is concerned that the trend is expanding to the federal level.

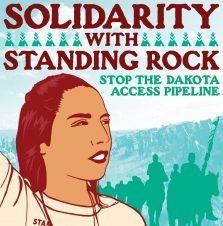

It was, in fact, at Standing Rock that Druid Casey McCarthy provided support to those pipeline protestors, the first of which were, similar to those in South Dakota, members of native tribes.

“I was aware before a lot of people were,” he said, and through contacts he made at the Pine Hill reservation, he was able to distribute needed supplies to protestors.

“We took a convoy of three vehicles, stuffed to the brim with supplies,” he recalled.

Some time later, McCarthy came back with more, this time supported by Mountain Ancestors Grove of the ADF, a group he once helped run. This was after media attention began its focuse on the situation in September, 2016, and he found that the changes to the camp were astounding.

“The camp was a total wreck,” he recalls. There had been an “influx of white people who totally trashed the camp and land. There was garbage everywhere, they were getting high a lot, and it was so bad natives were saying they were not actually helping, but there to take a selfie. They weren’t doing their part.”

In what he called an “interesting contrast of realities,” McCarthy witnessed native people “praying, crying, and holding ceremonies” while the newcomers “treated it like a festival. They wanted the ‘I partied at Standing Rock’ t-shirt, while others were being treated for bullet wounds, beaten with batons, getting attacked by dogs, and being horribly traumatized.”

McCarthy is a mental health professional who has worked with combat veterans, and said that the trauma experienced by front-line protestors at Standing Rock were on par with that caused by war.

Considering the protestors, McCarthy did moderate his language somewhat. “Not all white people are terrible, and some were allies, but there was a dichotomy. The indigenous people told me that this was nothing new.”

McCarthy feels that Pagans in particular owe more to Native Americans, since reciprocity is a common value and, as he says, “we’ve taken a lot from their cultures, and we’re not doing very much in return.” He’s mindful that extreme elements of the right wing also draw from the Pagan pool, but added, “We need to stop being afraid to rise up.”

In the long run, economics may be a bigger factor in these battles than politics or religion, but that’s not a gamble activists wish to make.

Martinez says many believe Keystone XL will never get built, because the price of oil is unlikely to rise high enough to offset the cost of refining bitumen extracted from Alberta tar sands.There’s also more oil in Venezuela than Saudi Arabia, and if turmoil in that nation eases it would be cheaper to put that in tankers than to build pipelines.

This development would relieve many of the people he speaks with, including one Nebraska farmer who said to him, “This is just plumbing, and plumbing leaks.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.