[Alley Valkyire is one of our talented monthly columnists. On the fourth Friday, she brings you insight and analysis about issues coming from within or affecting our collective communities. If you enjoy her work, consider donating to our fall fund drive today. It is your dollars and your support that make it possible for Alley and our columnists to continue their dedicated work, and for us to bring on more talented monthly voices. Please donate today and share the campaign! Thank you.]

I. The Discovery

A few weeks ago, it was announced that the wreck of the HMS Terror, one of two ships that comprised the long-lost Franklin expedition, was found on the ocean floor southwest of King William Island in what is now known as Terror Bay.

This discovery comes almost exactly two years after Franklin’s other ship, the HMS Erebus, was found farther southward in the same general area. Both were found by exploration teams that were financed by the Canadian government.

Many major news outlets in both North America and Europe have covered the story of both “discoveries” and to some degree have mentioned the history that has led to this point, but overall these media sources have failed to highlight the fact that the location of the shipwrecks have been known to local Inuit communities since the time of the exploration’s disappearance in 1848. Instead, the focus of the stories have mostly been on modern technology and due diligence, with only a few articles even briefly mentioning the Inuit.

Native and alternative media sources, on the other hand, have been stressing this crucial aspect of the story that Eurocentric media sources have summarily ignored: that the discoveries validate over 150 years’ worth of Inuit accounts, of orally-passed folklore concerning the fate of the Franklin expedition, accounts that were dismissed and ignored countless times by generations’ worth of European explorers and researchers. While European-descended Canadian explorers celebrate their “discovery” of the ships, indigenous voices are pointing out that “the Inuit were right”, a fact that mass media as a whole has failed to note.

II. The Officer

When Sir John Franklin of the British Royal Navy set off in search of a navigable route through the Arctic Circle, he was following in the footsteps of over 350 years’ worth of exploration attempts to secure a “Northwest Passage” for the purposes of trade between Europe and China.

Franklin sailed from England with two ships and 135 men in the spring of 1845, first traveling to Scotland and then to Greenland, where the exploration then sailed west through Baffin Bay. The last European sighting of the expedition was in July of 1845, when a whaling ship spotted the Erebus and Terror moored off an iceberg in Baffin Bay, south of what is now called Devon Island.

The expedition spent the winter of 1845-6 in an encampment on the western coast of Devon Island and attempted to sail on further in the summer of 1846, but the ships became trapped in ice off the coast of King William Island in Sept., 1846.

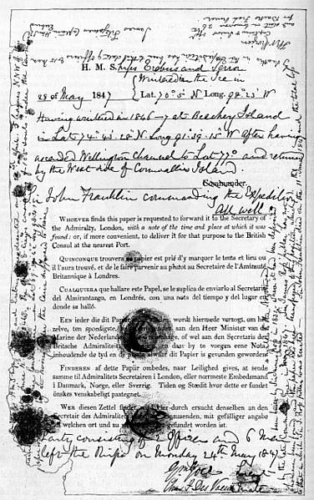

The note from Franklin’s crew, written in 1848 and found in 1859 . [Public domain]

None of the crew members ever made it to the trading post, and the most widespread and accepted theory from the time the note was found has been that both ships had sunk off the north coast of King William Island and Franklin’s crew died on foot en route to the trading post. For this reason, countless searches and rescue missions have been focused on the Victoria Strait and the northern part of King William Island.

But from the very beginning and for decades thereafter, that version of the story conflicted with numerous stories from the Inuit people, who relayed a different version of the fate of Franklin’s crew that was dismissed time and time again by those searching for the exploration.

Over 50 searches for Franklin and his crew were conducted in the decades after the disappearance of the ships and crew. Over time, more explorers and ships were lost in search of the Franklin expedition than the original casualty count of the Franklin expedition itself.

A route through the Arctic wouldn’t be discovered for nearly 60 years after Franklin’s attempt, when Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen successfully navigated the passage between 1903 and 1906.

III. The Lady

By all accounts, Lady Jane Franklin, the explorer’s wife, was a woman well ahead of her time. An famed explorer in her own right, she first gained attention for her travels through Australia while her husband was the lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land in the 1830s, and became a popular figure amongst the citizens of the colonies, noted for charitable actions and kindness. She was instrumental in founding early schools throughout the Australian settlements. She was also an early advocate concerning the conditions female convicts in Tasmania, and had corresponded with famed prison reformer Elizabeth Fry about their plight. Lady Franklin also was deeply involved in her husband’s career, with accounts detailing how she significantly managed his affairs and advised his career behind the scenes.

After her husband’s expedition was confirmed as missing in 1849, Lady Franklin devoted the rest of her life and much of her personal fortune towards finding what became of the it. She sponsored seven search parties to the Arctic between the time of the disappearance and her death in 1875, and used her social status and wealth to consistently bring attention to the unknown fate of her husband. She offered sizable cash rewards for information, and worked diligently to keep the story in the public eye and a matter of national interest.

[Amelie Romilly, public domain]

IV. The Search Parties

Scottish explorer John Rae was one of the first tasked with searching for the Franklin expedition under the authority of Lady Franklin, and he made three journeys through the Arctic from 1849 to 1854. In 1851, during an attempt to cross Victoria Strait towards King William Island, Rae described finding pieces of wood in the strait that had come from a European ship.

Three years later, while exploring the Boothia Peninsula, Rae came across local Inuit tribes who saw two ships trapped in the ice when they passed through in the fall on their way south. When they had come back through the area the following spring, they found multiple corpses and evidence of cannibalism.

When Rae relayed this information upon his return to England, he was initially credited with solving the mystery of the Franklin expedition and was granted the promised reward. Lady Franklin, however, reacted in horror, and many in the British press and upper classes, including writer Charles Dickens, shunned and publicly condemned Rae for suggesting that the crew would resort to cannibalism.

A few years later, in 1859, when Sir Leopold McClintock of the British Navy was searching for the Franklin expedition, a group of Inuit shared similar accounts of the fate of the missing ships with the explorer and his crew. They claimed that one ship sunk and another became trapped in the ice in an area they described as “Ootloo-lik.” During that same search expedition, McClintock’s team found the note left by Franklin’s men, describing ships trapped in the ice in Victoria Strait and the death of Franklin. When McClintock returned with this information, Lady Franklin apparently initially dismissed it, still convinced that Franklin was alive.

Five years after McClintock’s expedition, in 1864, American explorer Charles Hall was also searching for the Franklin expedition when he also encountered Inuit from the same region, who told him that they had stripped wood and metal from an abandoned ship that had been stranded in and crushed by the ice off the southern coast of King William Island. The ship had been found while seal hunting, there had been evidence that it had been recently inhabited, and a decomposing body had been found on board. They had also seen footprints leading to shore that were not made by Inuit.

These accounts contradicted the theory that was based on the note that McClintock found, that both ships had sunk off the northern coast of the island. The Inuit stories suggested that instead of following the river to their death, some of the crew members re-boarded the second ship and attempted to sail south, only to once again become stuck near the southern coast where they eventually perished.

And again in 1878-9, when explorer Frederick Schwatka and journalist William Henry Gilder searched for the expedition, they were told stories by local Inuits of skeletons found on the southern part of the island, and of compasses and watches and human remains found on the trapped ship. Once again signs of cannibalism were mentioned, of bones that looked as though they had been sawed off.

Lady Franklin had died a few years earlier, and could not personally refute these new claims as she had in the past, but nonetheless the claims were overall discredited and dismissed, in part because they contradicted the heroic narrative that had developed in the decades after Franklin’s disappearance.

Artistic rendering of the Franklin Expedition sailing through the Northwest Passage. [Public domain.]

V. The Legend

The disappearance of the Franklin expedition created a sensation throughout Victorian England. Franklin and his crew were quickly cast as romantic heroes and cultural icons in the eyes of the public, and Franklin was memorialized in countless ways, from statues erected to stories and plays and musical compositions written in his honor.

One of the earliest tributes to Franklin is arguably also one of the most lasting and well known testaments to his heroic status. The folk ballad “Lady Franklin’s Lament,” which first appeared around 1850, tells of the disappearance of Franklin and the subsequent heartache of his wife from the fictional point of view of a sailor who had a dream about Franklin. Countless versions and recordings of the song have been published over the years, more recently and famously by artists such as Pentangle and Sinead O’Connor.

The lyrics of the ballad beautifully capture the sentiments of the time:

We were homeward bound one night on the deep

Swinging in my hammock I fell asleep

I dreamed a dream and I thought it true

Concerning Franklin and his gallant crewWith a hundred seamen he sailed away

To the frozen ocean in the month of May

To seek a passage around the pole

Where we poor sailors do sometimes goThrough cruel hardships they vainly strove

Their ships on mountains of ice were drove

Only the Eskimo with his skin canoe

Was the only one that ever came throughIn Baffin’s Bay where the whale fish blow

The fate of Franklin no man may know

The fate of Franklin no tongue can tell

Lord Franklin alone with his sailors do dwellAnd now my burden it gives me pain

For my long-lost Franklin I would cross the main

Ten thousand pounds I would freely give

To know on earth, that my Franklin do live

Such sentiments, however, and the public image of Franklin that inspired such material, came up against many conflicts over the years as explorers brought back more and more information about the fate of the expedition, most notably the numerous Inuit accounts regarding cannibalism. From Lady Franklin’s public evisceration of John Rae to the subsequent dismissals of Inuit lore regarding the fate of the expedition, much of the denial of these stories was driven by the need to protect the public image of Franklin and his crew. The idea that the crew resorted to cannibalism to survive was highly offensive to Victorian-era sensibilities, as such heroic Englishmen would obviously never resort to such “barbaric” acts.

VI. The Bones

Searches for the Franklin expedition continued throughout the early part of the 20th century, but tapered off after the 1930s. The last notable expedition of that era was in 1931, when a manager for the Hudson’s Bay Company named William Gibson retraced the assumed route of the expedition on land and found several skeletons as well as pieces of naval cloth and wood from the ships.

Fifty years went by after Gibson’s finds without any other significant developments. Then in 1981, a forensic anthropology project backed by the University of Alberta started to search for remains of the expedition on the west coast of King William Island. Researchers found extensive skeletal remains, and they had the bone matter tested. The results showed that the crew members of the Franklin expedition likely died of vitamin C deficiency and/or lead poisoning.

Later excavations throughout the ‘80s and early ‘90s yielded bones with distinctive cut marks. Scientists then determined the cuts were likely the result of cannibalism, thus validating the various Inuit accounts as well as the reports from John Rae, whose name and career had been essentially destroyed as a result of accurately relaying what he had been told.

VII. The Discovery

In 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper initiated a new round of searches for the Franklin expedition, although it has been steadily argued that his intent was not to solve the mystery of the expedition as much as it was to assert dominance over the Northwest Passage and the Arctic Circle as a whole for the purposes of trade and profit.

Due to the increased melting of the polar ice caps, the Northwest Passage has become more easily navigable and for a longer portion of the year than it has ever been in the history of maritime exploration. This “development,” courtesy of climate change, has significant consequences for international trade as the “ownership” of those waters has long been in dispute. Canada claims sovereignty over the waters of the Arctic based on the British Empire ceding their claims to Canada in the 1880s, but the United States and many other countries consider the Northwest Passage to be international waters.

Additionally, the melting ice is also creating countless new opportunities for offshore drilling and mineral exploration, and the Canadian government has a significant interest in securing and asserting the rights to such explorations. Canada’s claim on the Northwest Passage has been framed as a matter of national interest, a message which has been specifically aimed towards Inuit communities in the Arctic Circle despite the fact that climate change and offshore drilling threatens the livelihood of those very communities.

Uncovering the wrecks of Franklin’s ships also factored prominently into the nationalist ideals that Harper’s government had promoted since taking power. The Franklin expedition was a key moment in the early history of Canada, and discovering the remains of the expedition would not only potentially legitimize Canada’s claims to the Arctic, but it would also inevitably strengthen the narrative that romanticizes the Arctic Circle as the birthplace of Canada as a nation.

For seven summers, Canadian anthropologists searched the northern, western, and southern shores of King William Island, uncovering numerous artifacts related to the expedition. They also conducted underwater searches both in the northern location where the note stated that the ships had become trapped as well as the more southward locations where Inuit lore claimed one of the ships had sailed before becoming permanently trapped.

In September of 2014, Harper announced that one of the ships had been found south of King William Island. At the time of the initial announcement, archaeologists had yet to determine which ship it was, but a month later it was reported that the find was the remains of the HMS Erebus, the ship that Franklin himself was thought to have died on.

But despite the fact that it was found in an area that matched the Inuit accounts of where it had sank, Harper’s public statement failed to mention those accounts and their importance in the discovery, instead lavishing credit onto various military and governmental entities before giving unspecified thanks to the government of Nunavut for their “tireless efforts.” Additionally, Harper’s government excluded representatives from Inuit communities from discussions and negotiations concerning the ownership of the finds, despite a legal agreement which grants 50% of archaeological finds in Nunavut to the Inuit people.Then in September 2016, it was announced that the “perfectly preserved” remains of the HMS Terror was found on the southwest coast of King William Island, north of where the Erebus was found but still 60 miles south of where the ships were assumed by Europeans to have been abandoned in the ice. Not only was it also found in an area that the Inuit had been mentioning for over 150 years, but the sunken positions of both ships in relation to where they were assumed to have abandoned also matches up with Inuit accounts.

Additionally, it is of note that the only reason that the search team was searching that specific area in the first place was due to hearing a story from a young Inuit crewman on their ship. He stated that he had seen a wooden mast sticking out of the ice in Terror Bay off the southwest coast of King William Island while on a fishing trip six years earlier. The search team was initially set to search in area described by the note found in the cairns, but after hearing the story from their fellow crewman, the ship decided to break with historical tendencies and for once a search party did not dismiss the story they had been told by a local. The ship then headed towards the location where the wreck was finally found.

But once again, the Inuit are fighting for a voice in the upcoming discussions concerning what is to become of the artifacts.

* * *

If there is any one consistent theme that defines the Franklin story from the very beginning to the present events, it is the belief in European superiority. From the earliest dismissals and outrage over Inuit accounts of the crew’s fate to the current denial of Inuit rights to the artifacts from the wreckage, its clear that overall the attitudes and actions on the part of those in positions of power have not changed much in over 150 years.

It is also that superiority which has fueled the relentless pursuits of strategic dominance that set the stage for both the beginning and the eventual ending of the Franklin story. The fact that the remains of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were only ever recovered in concert with Canada’s attempt to exert control over the very same route that Franklin died attempting to navigate is a notable synchronicity to say the very least. And its a connection that occurred as a continuation of the same imperialist and economic intentions that prompted the initial wave of European exploration through the Arctic in the first place.

As Inuit representative Cathy Towtongie told the Guardian:

If Inuit had been consulted 200 years ago and asked for their traditional knowledge – this is our backyard – those two wrecks would have been found, lives would have been saved. I’m confident of that.

But they believed their civilization was superior and that was their undoing.

* * *

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I’d like to see another cannibal musical, one based on this.