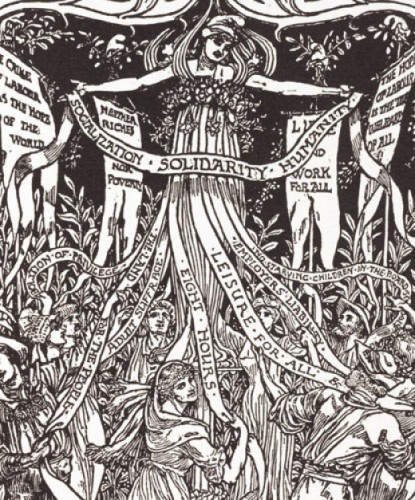

“Workers May Pole” (public domain)

When we tell the story of modern Paganism, we tell a history as we understand it. But all history is only selective memory, a collection of what we choose to remember or what we know to include. The sum total of humanity’s experience cannot be recollected except by the sum total of humanity.

History’s an exclusion, as much as it is a narrative, and tells us more what we think about ourselves now than what happened in the past. To recount the tale of myself to you would take my entire life, and that life is not yet over. I do not know what will grow from seeds planted decades before, how actions in my youth will unfold into the future. It’s all guesses, all suspicions, all hopes and fears.

To tell the history of a people is more difficult. What we choose not to remember or include matters just as much as what we recount, and this is even more true when we speak of a religion.

We’ve become self-conscious, apolegetic sometimes for our subversive ideas and uncommon beliefs. Gods and the Dead speak to me, but I do not always tell this to people. I practice magic, yet explaining to those unfamiliar with such things isn’t an easy task, nor one I’ve the tools to prove to the Disenchanted world.

Some of this self-consciousness and apology is merited, at least for those of us in supposedly-secular Western nations. Witches were once burned, academics are still fired for their Paganism, and the cult of Progress is the default civic religion of many modern peoples. But this is also fear, and no human should be ruled by terror, even as terror becomes the ruling logic of our societies.

Others have written brilliantly of the revolutionary and anti-authoritarian urge of witchcraft, but few write regarding the radical nature of modern Paganism itself. And it’s time for that history to be unburied, too, because we should no longer apologize for who we are, what we believe, and what we shall become.

Paganism is a revolt, a religion of The Commons of land, people, and gods, and the world now, with its dying forests, slaughtered species, and subjugated peoples needs this story as much as we need to tell it.

Progress and the Great Forgetting

Sylvia Federici has quite succinctly told the story of how the coming of Progress and the logic of Capital required the burning of witches, the subjugation of women, the eradication of Pagan beliefs, and the creation of a people divorced from The Commons. I won’t try to match her work, only to expound upon it.

Likewise, John Michael Greer has profoundly outlined the modern religion of progress and our unquestioning faith in Industrialized existence (with its alienation of human and earth, as well as its catastrophic destruction of the land, air, and water we Pagans hold sacred) ; I won’t try to match his work, either. And of course, Peter Grey’s work on Witchcraft as resistance is unmatched, and Starhawk‘s profound re-invigoration of the revolutionary stance of the Witch has influenced more people (Pagan and non-Pagan) than any of the great ‘leaders’ of modern Paganism. These four authors are essential to any understanding of Paganism, more essential than the great white “elders” invoked as ‘ancestors of the craft.’

But the story that isn’t told as much–yet–is the confluence between the rise of Capital and the resurgence of Paganism. That is, the coming of Progress and subjugation of peoples happened at the same time as Paganism became a resistance and revolt, an embrace of the fading Commons against the calamity of Progress and Capital.

Progress comes, and the forests die, the rivers slow then trickle. Icecaps melt, and glaciers, dumping ancient frozen worlds into indomitable seas. Great dark clouds fill the sky, choking out birds, leaving soot upon the brick and stone of human habitations, and the pipe and membrane of human respiration.

When we speak of Progress, too many think tech and tools, the artifice of creative mind meeting the urge to do less work. The shovel is not Progress, it is a tool—it made life easier, at least for those who dig. Nor is Progress the computer or the hand-phone, despite the lakes of toxic waste poisoning the earth that we might type at screens rather than scrawl upon paper. Again, these bits of silicon and coltan are tools.

Progress is a religion, not a technology, a belief that what is now is better than what was before, that as-we-are is greater than as-we-were, a faith in a future unseen and a hatred of the sins of our Pagan ancestors. Before we were stupid and poor, violent and sickly until Progress came with its saving grace. Before we toiled and slaved in darkness, revering unseen spirits, chanting praises to idols and dancing ignorant dances in the meadows of The Commons; now we’ve got video games and factories and fast-food, praise be forever to the Holy Name of Progress.

We are taught to hate what came before, to embrace what displaced our awful past, and offer fervently at the altars of Commerce and Capital for the better days to come.

“The old has passed away; behold, the new has come!” (2 Corinthians, 5:17)

In fact, Progress is a Christian Narrative, and the religion of Empire. Christianity, aided by Empire, subjugated, displaced, and destroyed many of our ancestral ways. But not all, for the Empire which wielded the Cross as a cudgel against the heathen and the druid crumbled, as all Empires do. Pagan ‘survivals’ abound, despite our historian’s trepidation at accepting the possibility that Empire might not be total.

“Empires Crumble” patch by Alley Valkyrie

The destruction of Paganism was never complete, nor could it be as long as shrines to syncretized saints held place within the chapels, candles lit and rags still tied by holy springs and sacred wells, and standing stones still stood.

The new can never replace the old, not fully, until the old is finally forgotten.

And thus the religion of Progress, the faith which keeps us tied to our jobs, our consumption, our obedience to Empire, and our slavish sale of our limited time in exchange for coin. But there was and still is a resistance to this religion, a revolt against the Landlords and Bosses, these priests who called “Progress” the theft of land, the subjugation of women, Africans, and indigenous peoples. And that resistance, that revolt? It was awfully Pagan.

Bacchantes in America, 1627

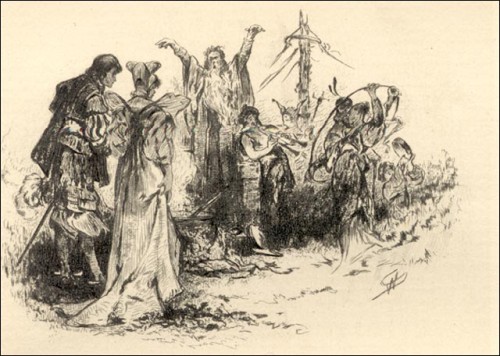

Illustration of Merrymount from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales (public domain)

Before Capitalism, there was The Commons, land shared collectively among a people. Meadows, fields, forests and rivers unfenced, used for grazing, gathering, dancing and living. This is a hard thing for us to understand, we who live some 300 years after the birth of “Private” property. It’s difficult to conceive of such places, particularly in our crowded cities and fortified suburbs, land not just open to all but un-owned, managed collectively and belonging to itself.

It’s difficult to understand The Commons particularly because all of our lives are currently enclosed and re-purposed. A street is not a place to meet people, it is a place to drive; parks are owned by cities, forests and lakes by governments, and even the places we live are ‘owned,’ by ourselves if we have money, by others if we are poor.

Enclosure created this state of existence—the selling off of land which was once un-owned and community-managed to individuals who could bar access to others from it. What was given to the now nebulous ‘community’ is in the hands of governments which regulate what can and cannot be done upon it.

Land ownership was a new thing, not just to peoples of Europe, but to those the European Lords of Progress colonized. And its in their experiences we can best understand The Commons that we lost. Consider the words of the Shawnee resistance leader Tecumseh, railing against agreements extracted (by force) from fellow tribes to ‘sell’ their land to the colonists:

The way, the only way to stop this evil, is for the red people to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was at first, and should be now — for it was never divided, but belongs to all.

No tribe has the right to sell, even to each other, much less to strangers.

Sell a country?! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children?

In fact, Native American/First Nations resistance to colonization (which continues to this day) not only helps us understand the coming of Private (exclusive) property, but also helped those conscripted (by force or threat of poverty) as foot soldiers of enclosure understand what their own ancestors had lost, even as the persistent Paganism of those settlers came with them across oceans.

You maybe don’t know much about that ‘persistent Paganism,’ though. This is understandable—even most Pagan historians speak little of this, if at all. For much of it, we actually have to look to Marxist historians, like Peter Linebaugh. From his The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of Mayday, comes this account of Thomas Morton, a colonist turned-rogue:

On May Day, 1627, he and his Indian friends, stirred by the sound of drums, erected a Maypole eighty feet high, decorated it with garlands, wrapped it in ribbons, and nailed to its top the antlers of a buck. Later he wrote that he “sett up a Maypole upon the festival day of Philip and James, and therefore brewed a barrell of excellent beare.” A ganymede sang a Bacchanalian song.

…Merry Mount became a refuge for Indians, the discontented, gay people, runaway servants, and what the governor called “all the scume of the countrie.” When the authorities reminded him that his actions violated the King’s Proclamation, Morton replied that it was “no law.”

Or as the Puritan Governor Bradford accounted of the very first Maypole raised in North America (again, 1627):

They … set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women, for their consorts, dancing and frisking together (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices. As if they had anew revived & celebrated the feasts of ye Roman Goddess Flora, or ye beastly practices of ye mad Bacchanalians.

Thomas Morton elsewhere, we should note, was accused of “heathenism” and of setting up Pagan idols, but admitted himself, in his own accounts, having hymns to Pagan gods (Venus, Cupid, Neptune and Triton) composed and sang in his liberated colony.

Queens and Cross-Dressing Rebels

Were this an isolated incident, we could perhaps ignore the colony of Merrymount, an aberration in history, a brief confluence of Pagan forms with Common revolt. But there are more evocations of Pagan gods in defense of the people against colonization and enclosure.

In 1761, a group of Irish folk, dressed all in white women’s clothing and made pacts to the goddess Sadhbh. Called Queen Sive’s Faeries, or the Whiteboys, they terrorized the wealthy landowners and merchants of several counties, pulling down fences, burning houses, and parading Christian leaders in horse-hair garb and thorns through villages. They issued manifestos, warnings, and eviction notices in the name of their Great Queen, demanding the ‘leveling’ of society, an end to the rich and a return to The Commons.

Said John Wesley, the founder of Methodism and a significant opponent of the rebellious and ‘Pagan’ tendencies of workers:

One body of them came into Cloheen, of about five hundred foot and two hundred horse. They moved as exactly as regular troops and appeared to be thoroughly disciplined. They now sent letters to several gentlemen, threatening to pull down their house. They compelled everyone they met to take an oath to be true to Queen Sive (whatever that meant) and the Whiteboys; not to reveal their secrets; and to join them when called upon.

And another un-named critic of that same time:

Their pretence for meeting was to redress the grievances upon the poor (as they termed it) by The Commons being inclosed. At first they executed their designs by levelling fences…

…They established councils at Stated places, where a president, Secretary and Members, considered of Everything relative to her Majesty Queen Sive’s interests, received petitions, gave answers to them, issued out menacing letters to creditors not to demand their just debts, to some landlords to remit their rents, to others to restore cattle&c….

This same reverence for a ‘mystical’ being, as well as cross-dressing occurred again, back across the Atlantic with the Molly Maguires, Irish worker groups who terrorised mine- and factory- owners in retaliation for poor working conditions, harassment, and murder of union organizers. The Molly Maguires also fought in Ireland and in Liverpool against the lords of Progress who’d destroyed the Commons.

Repression of them was fierce: mine-owners hired The Pinkerton Detective Agency, a private ‘police’ force at a time when policing was not yet fully a state-function, to crush their anti-Capitalist activities. Pinkerton still exists, by the way, it’s a subsidiary of a Swedish Security firm– Securitas— protecting Property, Progress and Capital throughout the world.

Many writers have already pointed out the confluence between Pinkerton’s violent suppression of predominately Irish workers in America with the events of May 4, 1886 in Chicago. Called The Haymarket Affair, the riots which ensued during a large labor rally calling for solidarity between oppressed factory and mine workers (and a call for an 8-hour workday) turned deadly as police moved in to disperse the workers. A bomb went off, police attacked workers, and thus was born May Day as most non-Pagans know it.

That is, there’s more than mere co-incident in the confluence of Pagan Beltane and Worker’s May Day, Thomas Morton’s May Pole at Merrymount does not seem such an isolated moment in American Pagan history.

Crones, Queers, and Ghostly Spear-Wielding Generals

Two more resistance movements to Progress and the return to The Commons in Europe are worth mentioning here.

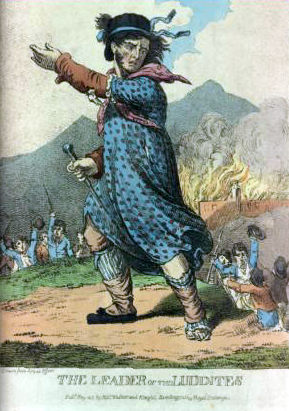

In Wales, some of the participants of the ‘Rebecca Riots,‘ (again cross-dressing rebels), claimed to have been led (and given clothing) by an old crone on a mountain. But better known were an earlier group who began issuing notices to wealthy landlords, factory owners, and to government officials who supported them. They demanded a return to The Commons and the end of the plague spreading across their land, the plague of industrialization. Called “Framebreakers” by the Lords and Mayors who sought their annihilation, they took upon themselves a different name, adopted from their mysterious King, “Ludd.”

These were the Luddites.

Their sovereign lived in a cave in a forest, had a shrine buried under a Christian chapel, and carried a giant pike. One of men charged with suppressing the Luddites and their mysterious leader recounted the experience of another who’d ‘met’ the strange being the framebreakers called their ‘general’:

he saw ‘one called General Ludd, who had a pike in his hand, like a serjeant’s halbert; I could not distinguish his face, which was very white, but not the natural colour’.

The Luddites were not anti-technology, despite what modern usage of the term might make us think. Rather, they were against that same “Progress” which asserted that it was better that humans work in factories for low wages than share among themselves the fruits of their own labor derived from The Commons.

As the Capitalist class (factory owners, landlords, etc.) sought to make more profit from the work of others, they industrialized production of goods, building factories and mills where workers (including children) would create even more goods-for-sale at the same (or even less) wages. Technology which made work easier did not benefit the workers (since they were still paid the same for their work), it benefited only the Capitalists. While the Priests of Progress (including many ‘Enlightenment’ thinkers) extolled the virtue of these new machines, the workers then were aware of the same thing many of us now also understand: the benefits of each new invention profit the few and cost the many.

That conflict is best described by Oscar Wilde (whose mother was involved in the Irish republican movement, whose wife was a member of The Golden Dawn, and who surrounded himself with Occultists and Anarchists) in his The Soul of Man Under Socialism:

One man owns a machine which does the work of five hundred men. Five hundred men are, in consequence, thrown out of employment, and, having no work to do, become hungry and take to thieving. The one man secures the produce of the machine and keeps it, and has five hundred times as much as he should have, and probably, which is of much more importance, a great deal more than he really wants. Were that machine the property of all, every one would benefit by it.

That is, another call for The Commons and the end of exclusive property.

There were other Pagans calling for the same thing in Europe, particularly in the very place the Enclosures and Capitalism started. Some of them were Naturalists and often Atheists like Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose support of the Luddites and radical poem “Queen Mab” wove together seamlessly with his calls for a Pagan revival. Edward Carpenter, a gay, socialist who dabbled in the occult, likewise espousing a return to the Pagan world of The Commons as a cure for the ‘disease’ of industrial civilization.

And some of these went on to lead Pagan religious traditions. Rarely mentioned in many histories of “Modern Druidry” is George Watson MacGregor Reid, an Anarcho-Socialist labor organizer who went on to lead the “Ancient Druid Order,” now called the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD).

The Unburied Past Inhabiting Our Present

The most radical part of our buried history is not so much the many intersectional revolts against Capital and Authority, but how Pagans are hardly the only ones to call on gods and spirits against the exploitation of people. One need only look at the Haitian revolution, one of the three great Democratic revolutions at the turn of the 18th century. Before it began, a group met in the woods called Bois Caiman, offering sacrifices and devotion to Ezilie Dantor.

Likewise, many indigenous resistance movements against the regime of Progress, Colonizations and Capital have called upon—or been led by—ancient gods and spirits. Devotion to Pachu Mama in South America inspires resistance to Capital now in Bolivia, and in Cambodia, ancestral land spirits (the neak ta) have regularly possessed textile workers to demand better conditions and a return to ancestral worship.

Why we don’t tell these stories, though, is another matter, one a bit difficult to speak on without eliciting howls of protest and defensive anger from those who’ve become established voices and leaders within American Paganism.

Paganism may be a revolt, but it is as colonized as other religions. For in every resistance to Progress and Capital and Authority, there have always been those more concerned with reaping the benefits of the ‘new order’ than building solidarity and community with others who struggle against it.

In fact, some even try to silence radical voices and keep concealed our radical past, either out of fear of ‘the burning times’ or, worse, complicity in the very system which keeps others subjugated. Capital pays traitors and opportunists quite well, though it often doesn’t need to. The hope of ‘succeeding’ in the current regime (be it becoming a popular author, a well-paid speaker, or other paltry bits of fame offered one) is enough for some; for others, a dislike of humanity; and for even more, an unquestioned life and refusal to see our colonized state.

But there are riots in the streets now. The forces of Capital and Progress cannot always keep hold upon the lives of everyone: the process of colonization and subjugation is never complete, as long as people have memory and hope for a return of The Commons.

And history, as I said, is memory.

It’s time we remember.

[Author’s note: I’m deeply indebted to the extensive research of historian Peter Linebaugh, whose works have already unburied much of this forgotten past, and to the inspiring work of the writers at Gods&Radicals, who are helping to ensure Paganism doesn’t forget]

This column was made possible by the generous underwriting donation from Hecate Demeter, writer, ecofeminist, witch and Priestess of the Great Mother Earth.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Interesting that Tecumseh did not mention fire and now in many places today they burn out of control……

I see a correlation between our Middle Class and the Commons. I can’t help but think that for progress in our time we would do well to focus on both.

Fires in the American west are the result of decades of bad forest service management. Persistent fire prevention allowed tons of underbrush to develop, turning forests into tinder boxes. The native Americans managed forest lands with fire which meant that the burns were under control. when they did happen.

Are you really sure that the Luddites have anything to do with Lludd?

considering that the people involved were 19th C Englishmen, first off it’s odd they would have any knowledge of Nudd/Lludd. The main suggestion is that it is from Ned Ludd who smashed up knitting frames in 1879, and who evolved into a folk hero and figurehead.

“the coming of Progress and subjugation of peoples happened at the same time as Paganism became a resistance and revolt, an embrace of the fading Commons against the calamity of Progress and Capital.”

Which time period are you talking about here?

the rise of paganisms in the past 60 years is largely a result of mostly middle class people who had the free time and whims to do so, as a result of spare time and money derived from Capitalism; Gardiner, Nichols etc

Several historians record the wild goose chase performed by captains and spies to identify the mysterious General Ludd. They’re quite hilarious, actually—including events where the Luddites would march in military formation and perform drills on a hill above a factory owners home in moonlight and be gone by the time any guards could get there. I don’t hope to do much better, though there’s an interesting Irish influence on the Luddites (who’d already had experience evoking sovereignty goddesses and ghostly figures–one of Queen Sive’s names was ‘ghostly sally’), and I’ve read some suggestions that Ludd may be Lugh.

Of course, there’s the more proper reading that suggests there never was a queen sive, or crone rebecca, or Captain Ludd but was a useful metaphor or a historical human given supernatural qualities. That being the same argument made about gods in general (people in the past didn’t really believe in them, they were historical figures, etc.), you’ll see why that’s a dead-end.

And I start modern Paganism earlier than Gardner/Nichols (which is the point of this essay); in fact, letting them define Paganism in its totality is exactly what polytheists such as you and I are attempting to resist, yes?

“That being the same argument made about gods in general (people in the past didn’t really believe in them, they were historical figures, etc.), you’ll see why that’s a dead-end.”

In some cases it is applicable. There is too much assumption that an appearance in the Mabinogion equals divinity, it doesnt. The mabinogion is a mass of myth, divinity, folktales and politics (Will Parker’s book on the mabinogion does a fine job of untangling this). The gods are in there, or at least echoes of them and untangling them is part of our devotion; seeking them out, erecting their shrines again and speaking their names over libations.

I think we need to be aware of paganwashing people in the past, they were most likely staunch Christians and to suggest they were followers (for want of a better word) would be to do them a disservice and disrespect.

That last bit deserves an entire book, particularly since our view of Christianity is so defined by the present fundamentalist strands which speak both of purity and totality.

For instance, Thomas Morton was an Anglican who set up a May Pole with Algonquins and had hymns to gods composed and sang before gay orgies. What was he, then–Pagan, Christian, or some mix thereof? Our tendency to look for pure strands (pure Paganism/polytheism on our side, pure christianity on the Christian side) doesn’t fit any really-lived experiences in the present, let alone the past.

In fact, the Puritans (whom Morton was defying) were all about this, stripping out the vestiges of Pagan worship and idolatry from the True Religion. Were they seeing Paganism where it wasn’t, or were they seeking purity where it cannot exist? That’s a perennial question not just for reconstructionists and historians, but for really-lived religion anywhere.

“Our tendency to look for pure strands (pure Paganism/polytheism on our side, pure christianity on the Christian side) doesn’t fit any really-lived experiences in the present, let alone the past.” <– THAT. Bravo. Well-stated.

You’re right that the lines between Christian and Pagan were blurry back then. Thomas Morton was an educated man and knew his Latin classics. He was a product of that Renaissance spirit that saw value in the wisdom and art of the ancient Pagan world and tried to adapt them to Christian Europe. It’s like when you see a Catholic Cathedral in Italy and find it filled with Roman images, or when the Roman gods show up in some of Shakespeare’s plays.

It’s obvious from his writings that Morton also had a good sense of humor and really liked to enjoy himself…

erm, 1779. Says Wikipedia: In 1779, Ludd is supposed to have broken two stocking frames in a fit of rage. After this incident, attacks on the frames were jokingly blamed on Ludd. When the “Luddites” emerged in the 1810s, his identity was appropriated to become the folkloric character of Captain Ludd, also known as King Ludd or General Ludd, the Luddites’ alleged leader and founder.

Well done Rhyd, a valuable contribution helping us better understand and appreciate our history.

This thing with the commons too – from what I have looking at, they werent owned collectively by the people, they were owned by the manorial lord/boss chap. It was that tenants had rights to make use of the land for grazing, they never owned it. this is what seems to have been the case in Britain

This is an interesting question. What we are really talking about here is the nature of “ownership.” If a people are able to utilize land in the collective, then it doesn’t really matter who owns the land. Not until after Enclosure, when common land utilization was prohibited, did the distinction about ownership as privatization become so important.

As far as I understand it, nobles under feudalism didn’t own land as such, they just had legal control over territory on behalf of the the monarch. They couldn’t just do whatever they wanted with the commons, because it was understood that the commoners had well-established rights to those areas.

That’s my understanding too; they were tenant in chief. I don’t have the willpower to do a proper look into what ‘power’ they could exert over the peasant tenants. annoying lack of info on Anglo-Saxon law easily available right now.

Ironically just been watching a programme about sheep farmers in North Wales taking the herds up to common land in the mountains

Which is what Beltane was actually all about, at least in the Scottish Highlands!:)

Now *this* is a Pagan blog worth reading. Not a breath, but a gust of fresh air.

Brilliant, vivid connections…!

Thank you, Rhyd. Many of us saw the whirling, weaving strands as the turning of the Whorled- Wheel, with energy returning to the Mother and back out into the peoples, struggling for rights and justice still.

All hail the multiple faces of the Queen of the May!

Pythia

Excellent and quite educational. Thank you.

Memories within memories! Thanks for ferreting out some good ones!! The telling of lost stories is a true modern spiritual path.

There seems to be an editing error which you might want to correct since this essay is probably going to be widely quoted, excerpted, and linked. In the sentence that starts, “Likewise, John Michael Greer . . .”, “industrialized existence” is the subject of a subordinate clause which is missing its predicate. From the context, I would infer some form of “is” and an adjective or another clause.

Oh dear. It’s missing a predicate indeed. Repaired, thanks. 🙂

One other small edit: the caption on the Merrymount photo above says “Twice-Sold Tales.” Hawthorne’s collection is called Twice-Told Tales, whereas Twice-Sold Tales is a used bookstore in Seattle. 😉

teehee. fixed!

Fun that you know -precisely- why I made that mistake, my friend! 😛

What can I say? I’m a big Thomas Morton fan, and a big Seattle fan! 😉

Myths are stories that tell us how it is best to live in our communities. But it is important to distinguish between myths, which most often provide some sort of moral message, and scholarly fact. Like stories Gardener told about the beginnings of Wicca, the tale of a matriarchal societies, and of the 9 million women burned to death in witch hunts, the idea that people owned property in common before the advent of the industrial age is a myth.

That such a myth exists, and is found to be wholly believable is not surprising. Utopian fantasies go back at least to Plato and would seem to be a natural human tendency. The native Americans did indeed have a concept of property rights, although the systems they used were so alien to Europeans that they were not recognized for what they were. Such rights ranged from tribal to familial but they did exist. The Mahicans of the Northeast had hereditary gardening rights along fertile river valleys. They did indeed sell some of this land to European settlers. Further from the rivers, the land was not valued because they were so rocky that farming was not worth the trouble and so ownership was not established. The Creek farmed their own familial plots and kept food in personal store houses. In the Hudson Bay and St Lawrence river hunting groups recognized clan areas and respected territories. There are numerous other examples. Personal items were always privately owned. Women were often in possession of housing, utensils, and clothes and these were sources of personal wealth acquired by their own labor. Ownership encouraged careful management of resources so that there would be resources available for the future. It was the Dawes Act of 1887 which collectivized land ownership for native Americans and they have been living in poverty ever since. And there is no evidence in any ancient society that property was held in a way that knew no boundaries.

The Commons is not a recipe for fruitful survival, but for starvation, want, and environmental disaster. There are numerous examples of common ownership that have ended poorly. The pilgrims started their new colony with common farming. They almost starved to death the first winter. Once they decided to deed each family a plot of land to care for on their own, magically, enough food was produced to pass the winter in health. Other examples, all of which broke down include the Jamestown Colony, New Harmony Indiana founded by Robert Owen, and the Oneida Colony. Countries that have communalized property have a record of horrific environmental disasters. A very small number of the many examples include air pollution in China, the Aral Sea (just look it up), and the Xtoc I oil spill.

The idea that we should strive for common ownership of land or goods is not useful or even good for the environment.

Hi Selina;

You cited an ‘environmentalist group’ funded by the Koch Brothers to prove that Native Americans are better off under Capitalism. (http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Property_and_Environment_Research_Center)

Also if this is true:

“the idea that people owned property in common before the advent of the industrial age is a myth,”

then the rest of your statements arguing against a return to The Commons are nonsensical, and Adam Smith (and other)’s arguments against letting The Commons remain, and the explosion of protests (with letters demanding a return to The Commons) and several hundred years of parliamentary records, are completely fabricated.

You also conflate Personal and Private Property No Marxist, Anarchist, or Socialist argues for the seizure of personal items. Even the most Totalitarian regimes with their heinous crimes never made people share underwear–but Disney did.

Private Property refers to land. This is clear everywhere in anti-Capitalist thought, but you’ve elsewhere admitted you’ve never read Marx or other anti-Capitalist theorists, so I must suspect you are arguing against strawmen you’ve encountered from Libertarian caricatures of those nasty communists who want to take away your socks.

You espouse the same circular logic and shifting conflations elsewhere, make assertions that people believe things they do not (central planning, etc.), and suggest that people who no longer wish to engage with you “were not available to be convinced,” which is why many people choose not to engage in these discussions with you. In fact,if feels remarkably like arguing with a young earth creationist, and I unfortunately have no interest arguing with them, nor with you.

Interesting article–some superficial comments:

a) love the Pre-Raphaelite/Art Nouveau wood cut, as I love that period in European art.

b) many folk want their electronic tools/software to stop changing all over the place because some marketing person or software engineer thinks it’s a cool idea. We want a hammer, not a racheting screwdriver disguised as a hammer, but they never thought to ask the general run of consumers.

c) Knew of General Ludd, as well as the Rebecca Riots, through folksong and historical novels (even historical romance!), and research I did after hearing or reading.

As always, you give me fodder for thought.