Disney’s most iconic animated villain has returned to the big screen in a live-action fantasy that twists and soars as it fractures the original fairy tale upon which it’s based. At its simplest level Maleficent is an extended re-imagining of Disney’s animated Sleeping Beauty (1959) with a focus on its well-known, dark-cloaked villain. However in presenting this alternative perspective, the live-action film dabbles in contemporary feminist, religious and ecological themes as it takes you through its fantasy world.

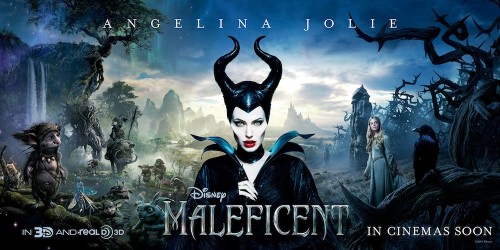

Courtesy of Disney (Film Poster)

The story begins with Maleficent as a young fairy living in the Moors, a world of enchantment and peace. She eventually meets Stephan, an orphan human boy from the greedy human world. The story then follows them, through love, to adulthood as she becomes the strongest fairy and he pursues his dream to live in the castle. Stephan’s ambition eventually leads to a violent moment of betrayal which directs the film’s plot into the Sleeping Beauty narrative complete with the famous “Christening” scene. The rest of the movie faithfully follows the animated classic’s story but with a different lens, so to speak.

Maleficent is not a Hollywood or studio trend-setter. The film is simply another serving of a villainous character back story (i.e., Star Wars, Wicked, Oz the Great and Powerful). It also follows Disney’s somewhat misguided interest in revisiting their animated classics as live-action films (i.e.,101 Dalmatians, Jungle Book) or Broadway shows (i.e., Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, The Lion King). Some work and some don’t.

Interestingly in 1959 Disney’s Sleeping Beauty was a critical flop. Walt Disney called it an “expensive failure” saying “I sorta got trapped.” Audiences expected the softer and safer Cinderella (1950) but got a more stylized design and a darker, more frightening villain. Due to the film’s failure, Disney would not to return to the classic princess narrative for another 30 years.

![Courtesy of Disney [Promotional Poster 1959]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/7071338_f1024-500x375.jpg)

Courtesy of Disney [Promotional Poster 1959]

Directed by Robert Stromberg, the production designer for Avatar (2009) and Oz the Great and Powerful (2013) and written by Disney Veteran, Linda Woolverton, Maleficent contains stunning imagery surrounding its decidedly feminist tale. Visually speaking the fantasy world has a hazy “story land” mystique without being cartoony or campy. The human world is murky and muted while the enchanted land beyond the moors is vibrant and mystical. The magical creatures are rendered with a fantastic realism that recalls the art of Brian Froud.

The most striking visuals are of Maleficent herself, who is portrayed to perfection by the talented Angelina Jolie. From start to finish, the film’s narrative rotates around her nearly to a fault. There are very few other elements, exchanges or characters whose screen presence command the same level of attention as Jolie. She makes this film. It is Jolie’s show and that manages to work because, after all, it is Maleficent’s story.

There were moments, however, that the film felt more like an explanation of the animated classic rather than a film in its own right. The plot moved from one moment to the next gliding behind the radiant Maleficent in very much the same way as the sleeping Aurora floats behind her on the trip to the moors. Many filmic elements get lost in her wake as the plot winks at the audience as if to say, “See that’s what really happened.”

That is not to say the film doesn’t contain any interesting sub-textual themes. Maleficent presents a number of complicated contemporary ideas. For example there is an Avatar-inspired eco-subtext winding through the plot. We cheer for the peaceful mystical moors and against the greedy human world. In this way, Maleficent could be considered an Earth Mother and Protector who violently avenges the pillaging of the land and eventually finds balances through the cycle of life.

The secondary characters are, with no exception, secondary or less than secondary. Like the narrative they live in shadow of Jolie’s Maleficent. With that said, Sam Riley as the Crow is a well-played, fascinating addition. The two most disappointing characters are Ella Fanning’s Aurora and Brenton Thwaite’s Prince Philip. Both are out of place in the earthy, magical realism presented by the rest of the film’s design. Aurora recalls her “unmemorable” animated counterpart. The film could have handled a stronger, grittier princess or an “Aurora unplugged.” As for Thwaite, his “boy band” appearance and glossy smile are better suited to a Disney Channel sitcom than a subversive dark retelling of a classic fairy tale.

Movie Still from Disney’s Maleficent

Overall Maleficent is very satisfying and fun to watch. It is worth the ticket price just to see Angelina Jolie capture the iconic character. The film contains battle scenes, dragons, tree guards and hairy human kings. But what is most engaging about this film and what keeps the narrative from sinking into obscurity is two yet to be mentioned themes.

From this point forward, this article contains spoilers. Do not continue reading if you have not seen the film and prefer to be surprised.

Aside from the Avatar ecological subtext, there are two other notable themes in Maleficent that cause the fairy tale to fracture. The first is the theme of the “fallen angel” and the second is that of the “anti-mother.” Both have distinct feminist tones which, in recent years, Disney has been attempting to nurture.

Before going forward let’s get one thing straight. The story is not told from Maleficent’s point of view. The narrator is revealed to be Aurora. As the story opens, she tells us that we’ve been more or less “dealt a bag goods.” Here’s how it really happened…

The theme of the “fallen angel” is presented both visually and narratively from start to finish. Maleficent is a fairy with large feathered wings that drag on the ground and tower above her head. Near the beginning of the film, she flies up to the clouds, faces the camera and opens her wings. This imagery recalls an angel against the sky.

When Stephan performs the violent act of cutting off her wings, Maleficent is grounded. She becomes the “fallen angel,” a process that is further demonstrated by the darkening of the moors and the skeleton imagery behind her throne. Hatred and vengeance consume her as she becomes the dark queen with all the expected iconic trappings of a sorceress or devil character such as a staff, black leather cap around her horns, black clothes and a crow. She becomes the vengeful dark “fallen angel” or as she is called in the film, “witch.”

Only childhood innocence can penetrate through her hate. When she finally displays love again she earns back her wings. However, as demonstrated visually, she doesn’t simply return to her former self. At the end Maleficent retains her dark, gothic appearance, her crow familiar and her magical staff. Secondly, near the end of the film, she flies into the sky as she did at the beginning. Just before striking the angelic pose, she pauses in profile with wings outstretched which recalls the Winged Nike – a symbol of victory.

Maleficent is essentially driven to revenge not simply because she was scorned but because she was physically violated. Her body was cut and part of her life stolen. However she finds a new life through the love of a child and that is where Disney fractures another classically embedded fairy tale theme – the “anti-mother.”

Traditionally the “good” mothers are either biological grandmothers or, more often, fairy-god mothers. In Maleficent, these typical good mothers are absent or incompetent. The three “aunties” don’t know how to feed a baby or bake a cake – two common signs of the “good mother.” At times the three pixie women have more in common with the witches of Hocus Pocus (1993) than the three good fairies of Sleeping Beauty.

Movie still from Disney’s Maleficent.

It is the “anti-mother” or dark witch who actually cares for the child and keeps her safe. Where the fairies are tired of raising Aurora, Maleficent and the crow protect her and become her shadow guardians. In a complete reversal, the film turns the “anti-mother,” who is typcially jealous of youth, into the good or “godmother” as Aurora says. In this way, the godmother and the fallen angel are one.

Becoming the good mother saves Maleficent from herself but, fortunately, does not transform her into something she is not. She remains the dark-clad, powerful gothic fairy. In doing so, the mother – daughter bond, typically absent from fairy tales and Disney animation, is rediscovered and allowed to thrive. This is punctuated by the film’s twist on “true love’s kiss” which was, unfortunately, predictable due to Frozen (2014).

If you add in the ecological subtext, Maleficent is a visually beautiful film with dynamic elements that circle around its spectacular title character. While the film could have explored relationship dynamics and narrative elements more in-depth, the film compensated with interesting themes, beautiful visuals and Angelina Jolie.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Saw this the other day. Very disappointed with it. Yet another example of the degradation of the faery tale.

I was completely appalled by the (Frozen-esque) “True Love’s Kiss” concept. It renders the basic concept obsolete.

Hmm. I took it to be a warning to look for true love in the not-so-obvious places a lover might take.

The point is that, if familial love is the same as “true love” of faery tales, why is a curse that can only be broken by true love anything to fear?

Well familial love might not always be true love either, anymore than Phillips first-sight infatuation with Aurora was: some familial love is engaged in more out of a sense of obligation.

Indorri, you have a point, as did Leoht.

I have seen some families completely lacking in love for their own. Sad, very sad.

It is a long established fact (of faery tale lore) that “true love” is of the “eros” type love, rather than the “philia” form of love.

I won’t comment on the new movie since I haven’t seen it.

I saw Sleeping Beauty in its first theatrical release as a child of ten. I watched it again in a theater decades later, after having become an ideological feminist (I was always an instinctive feminist) and a witch. I was struck by how much that movie adhered to a trope that was universal in American popular culture of the 1950s and 1960s, which I hated as a child and still hate. It was that women who are both sexy and competent or intelligent are always villains and nearly always brunettes (I was a brunette).

Watch almost any movie or TV program from that period, whether comedy or melodrama, and the nominal heroine will be a dumb, helpless blonde. Any woman with a smidgen of sexual attractiveness who shows some ability for independent action is an evil, evil, evil brunette. To be an acceptable girl or woman, act weak and dumb, and dye your hair.

Since the revival of feminism, I’ve seen waves of attempts in American popular culture to break out of this poisonous dichotomy. Almost fifty years later, most of the alternatives offered still seem to be self conscious and formulaic, not felt naturally and not drawn from life. I can think of one TV show that does not stereotype women in this way, and is a commercial and popular success, The Good Wife.

Samantha Stephens. Of course her mother is very much a redhead….Yes, Samantha has to act dumb around her husband (sometimes) and his co-workers (all the time), but nonetheless those of us watching know how smart and wise she is. She was sometimes the only female character on TV, of that day, of any power NOT villanized.

Take Dobie Gillis. Dobie himself isn’t the brightest (and don’t ask about Maynard), but Tuesday Weld (whose name I can recall better than her character on that show), and Zelda Gilroy? certainly played to that tune of blond/brunette values.

I think it’s great that both Dwayne Hickamn (Dobie) and Sheila Kuhn (Zelda) both went into political life & activism.

I always liked Zelda better, but then I’m short, brunette, and did very well in school.

TBH, I found the wing-stealing scene – or rather, her awakening afterward – to be reminiscent of rape. Which makes sense, given the Earth Mother theme. Greed has raped and stolen from the natural and magickal world.

I had much the same reaction. I could understand her rancor against Stephan after that.

So many Glaswegian accents!

SPOILER SPOILER SPOILER

I was a little confused how she became the queen, since there was no queen prior to her wings being clipped.

Obvious display of power.

I saw the film today with a friend of mine who is also a witch and polytheist and we both loved it. I think this is the kind of fairy tale our culture needs right now. I also liked that it showed how a character depicted as malicious can gain allies and friends, which is something we rarely see in the usual hero epic. Also, I felt like Maleficent herself was taking on a sort of sacred regency and had gained the respect of her fellow denizens for being a friend and defender before her violation.

Also, the film does a great job illustrating both (Egyptian) ma’at and (Germanic) wyrd and orlog. In ma’at, all actions have consequences, and even malicious action can be atoned for in some way. With wyrd and orlog, where wyrd is equated to fate (I know Heathens, I know, it’s more than that), Maleficent ties hers with the child, and his father, and no matter what she does she cannot escape that connection. She also cannot do anything to undo her curse but does find a way to make everything better. Also note that in doing so, she is able to heal.

The last three Disney fairy-tale movies had strong female characters who formed strong bonds with other female characters and passed the Bechdel test easily.

Coming of age stories for young women are seldom seen in movies unless it’s with/through a male love interest. Brave did that, while exploring the mother-daughter bond (and the lesson of being quite sure and specific in what you ask for). At the end, there was no male love interest, either. Lots of red hair, though!

Frozen had two strongminded women, which can be encouraged in royalty for some odd reason ;-}, and there was a coming-of-age trial for each of them. I had a small consistency issue with the young (blond) Elsa being told to cut herself off from everyone, that her power could only bode ill and she must control it (read suppress) at all costs. At the end, touching, no problem; magic use, no problem when it comes from a loving heart–which she certainly had had as a child when (brunette) Anna got a white stripe in her hair. BTW, for me, Let It Go wasn’t the music that got my attention–the Scandanavian women’s chorus’s songs did.

Magic, magic, and magic.

Heather, I agree with you that Aurora was rather bland and toothless, but Philip really was just too pretty-face non-entity for me. Was that a writer/studio decision, to keep the interest on Maleficent? Wasn’t necessary–Jolie can hold her own.

As to recalling Froud, I’d swear some of those critters were right OUT of Froud’s work.

I did enjoy the movie–I’ll happily take my belle-mere and look for scenic elements I might have missed the first time.

Are there many coming of age stories for young men in movies (without a female love interest)?

All coming of age stories traditionally include a love interest. It is part of the process.

However, traditionally/generally speaking, male coming-of-age stories are not dependent on that romantic interest. The maturation process is defined by a victory or some personal achievement. (Lion King or Tarzan for Disney example) The boy takes his rightful place in society. The “love interest” is simply the prize. For girls, the maturation process is defined by, triggered by and dependent upon the love interest. She moves from Daddy to Husband or King to Prince. But Disney’s been messing with this standard since the 1990s. (see Mulan)

Disney destroyed Mulan and Tarzan, much like they destroy all stories they touch.

I am still not convinced that there are that many “coming of age” stories for young men. Certainly none recently.

I’ve seen scores in the non-disney genre, too numerous to mention. Just go to family video and look on the racks. Finding ones for young women otoh isn’t as easy, and as noted, usually involve a boy. A rather interesting one though that intrigued me as also very much more well-acted and complex for both genders is The Perks of Being a Wallflower. Although I only watched once, I’d like to watch it again. It surprised me.

I have two boys. I struggle to think of a decent number of male coming-of-age movies.

It very much seems that “coming of age” is something that females do.

(An argument is often made that males never grow up, they just get older. 😀 )

I you looking for recent, or in general?

Ideally recent, for my two (both pre-teen), but even “in general”, I can’t think of too many.

Harry Potter?

See, I am not convinced that it is a “coming of age” story as much as it is a “prophecy/destiny” story.

It is also not all that recent, any more.

“For girls, the maturation process is defined by, triggered by and dependent upon the love interest.”

I disagree – there are tons of coming-of-age stories that feature clever, strong protagonist girls who either have no love interest at all or where the love interest is incidental to the main action. Check out the examples I’ve collected over at Girls Underground: http://girls-underground.com/the-archetype/examples/ (not all are coming-of-age stories, per se, but plenty of them are)

I enjoyed Maleficent quite a bit. I was hesitant about finding out my favorite evil fairy wasn’t quite so evil (or even slightly evil at all in the end) but I was moved by the choices they made with her character. It was a visually stunning film and Jolie is statuesque throughout.

The removal of the “evil” was one of the biggest disappointments, for me.

Why do we need a sympathetic villain? What is wrong with having a “big bad” to celebrate the vanquishing of?

Well, it’s more they switched the villain around and played with it. Original: good king and his daughter, bad witch who curses them.

Remake: guy who starts off good but becomes “evil” (though I guess even he becomes a little sympathetic given his fall was instigated by Maleficient’s curse), girl who starts off good, becomes evil because of betrayal, becomes good again.

Honestly, the more I reflect on it, the more I like what they did with the moral aspect of the story.

They made the whole thing ambiguous. The heart was ripped out of the story for the sake of Disney’s corporate gratification. The changes have added nothing to the actual tale and serve only to further degrade yet another faery tale.